ENGLISH This is an English translation of parts of the site www.nolahatterman.com. Information about Nola’s acting career and her poetry is not included. If there is a need for information about these topics, please send an e-mail.

Also I want to bring this blog to your attention.

ABOUT THE WEBSITE | BIOGRAPHY | WORK | EDUCATION

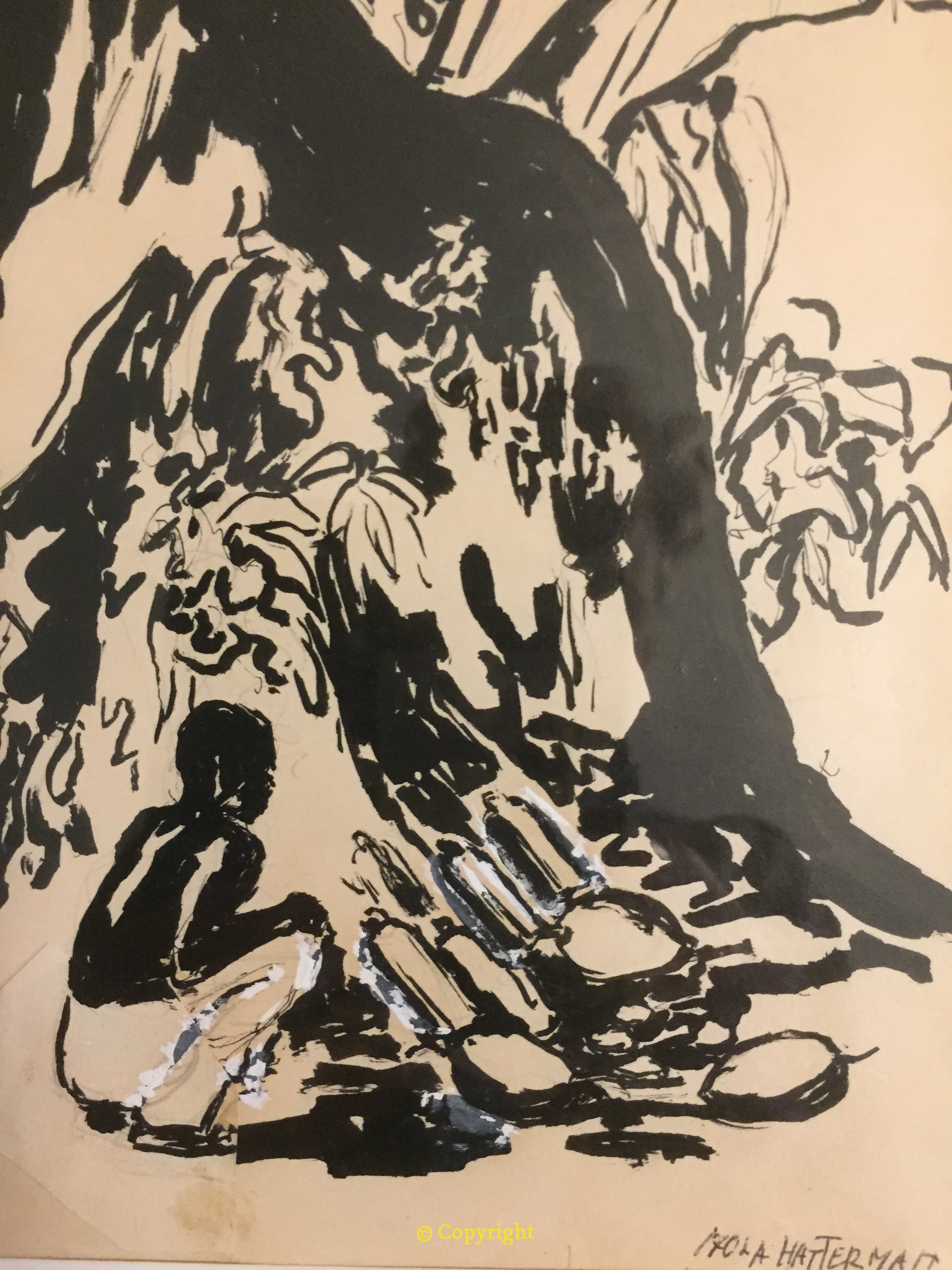

Visual art | Illustration | Decorations | Lost work | Finds

OEUVRE | ABOUT | FORUM | CONTACT

ABOUT THE WEBSITE

The aim of this project is to generate multimedia attention for the remarkable artist Nola Hatterman (1899-1984) and her legacy,  preferably in the form of a digital oeuvre catalog of her work, a monograph (in addition to the biography), a documentary and an exhibition of her paintings and that of her Surinamese pupils and contemporaries in one of the Dutch museums and Surinamese art institutions. This project is supported by the Mondriaan Fund.

preferably in the form of a digital oeuvre catalog of her work, a monograph (in addition to the biography), a documentary and an exhibition of her paintings and that of her Surinamese pupils and contemporaries in one of the Dutch museums and Surinamese art institutions. This project is supported by the Mondriaan Fund.

Comeback

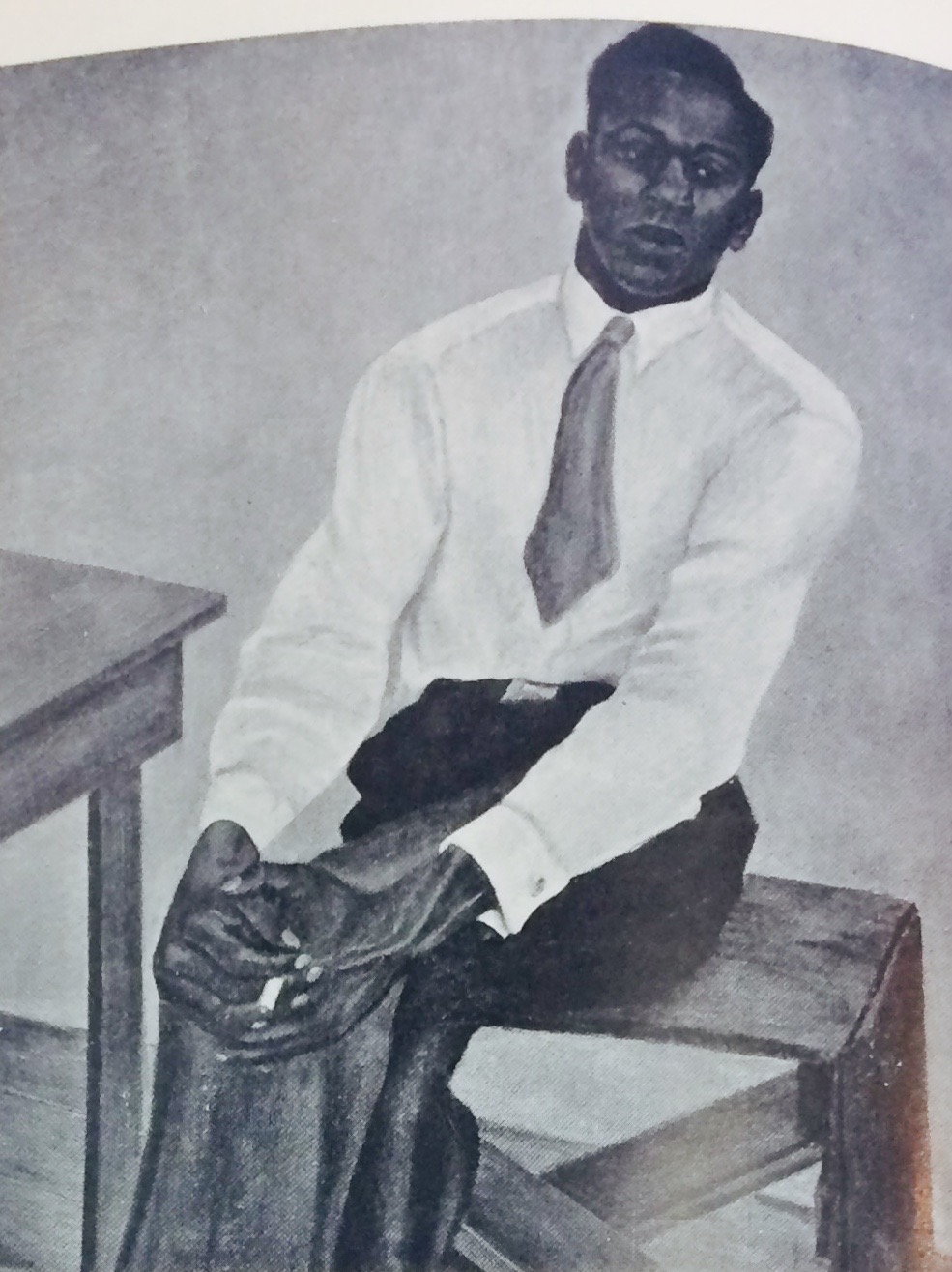

In 1999, Nola Hatterman (1899-1984) posthumously made her entrance in the Netherlands at the expo ‘Magie en Zakelijkheid’, Magic and Realism, the realistic painting in the Netherlands from 1925-1945. The presumed lost painting On the terrace (1930) was in 2008 also the eye-catcher during the Black is beautiful exhibition in De Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. Nowadays it is part of the Stedelijk Base, the permanent installation of iconic works from the collection of the Stedelijk Museum. The man on the portrait is known as the musician Lou Drenthe.

Ph Ellen de Vries On the terrace (1930), Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

White

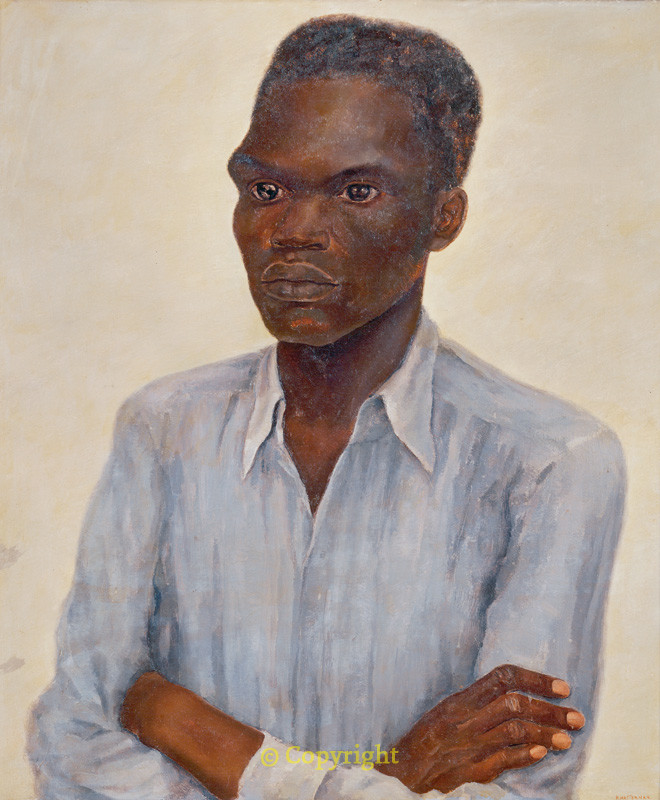

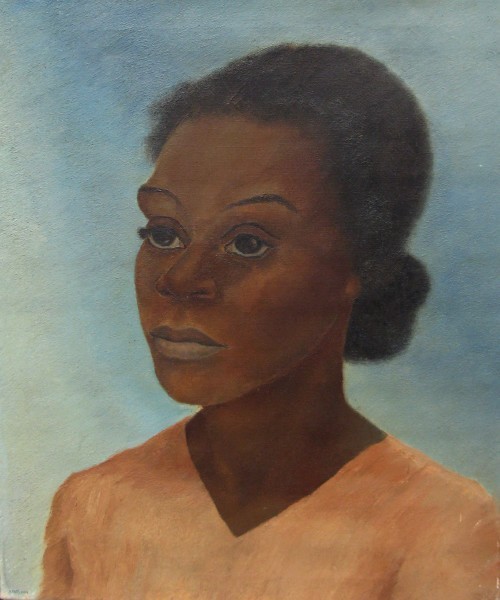

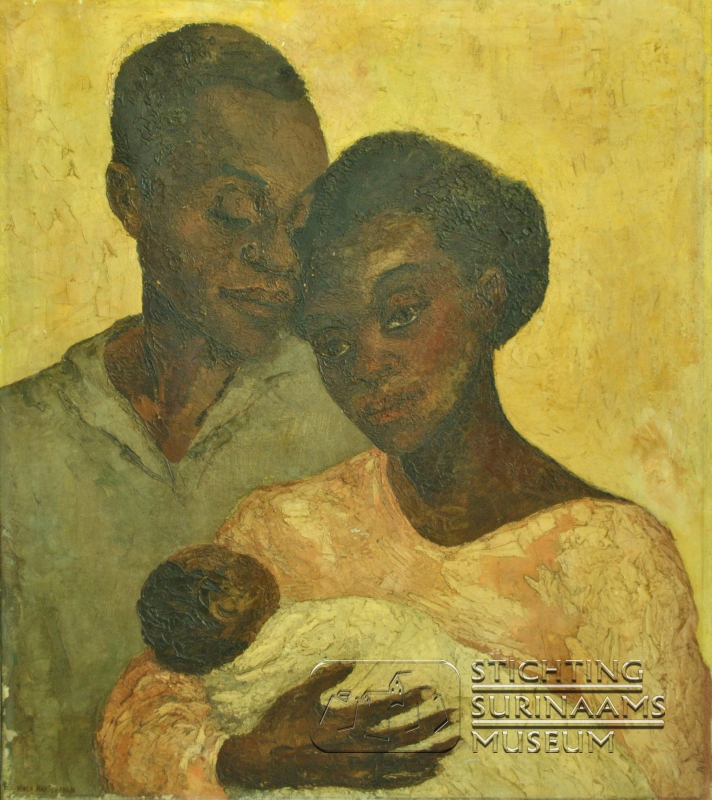

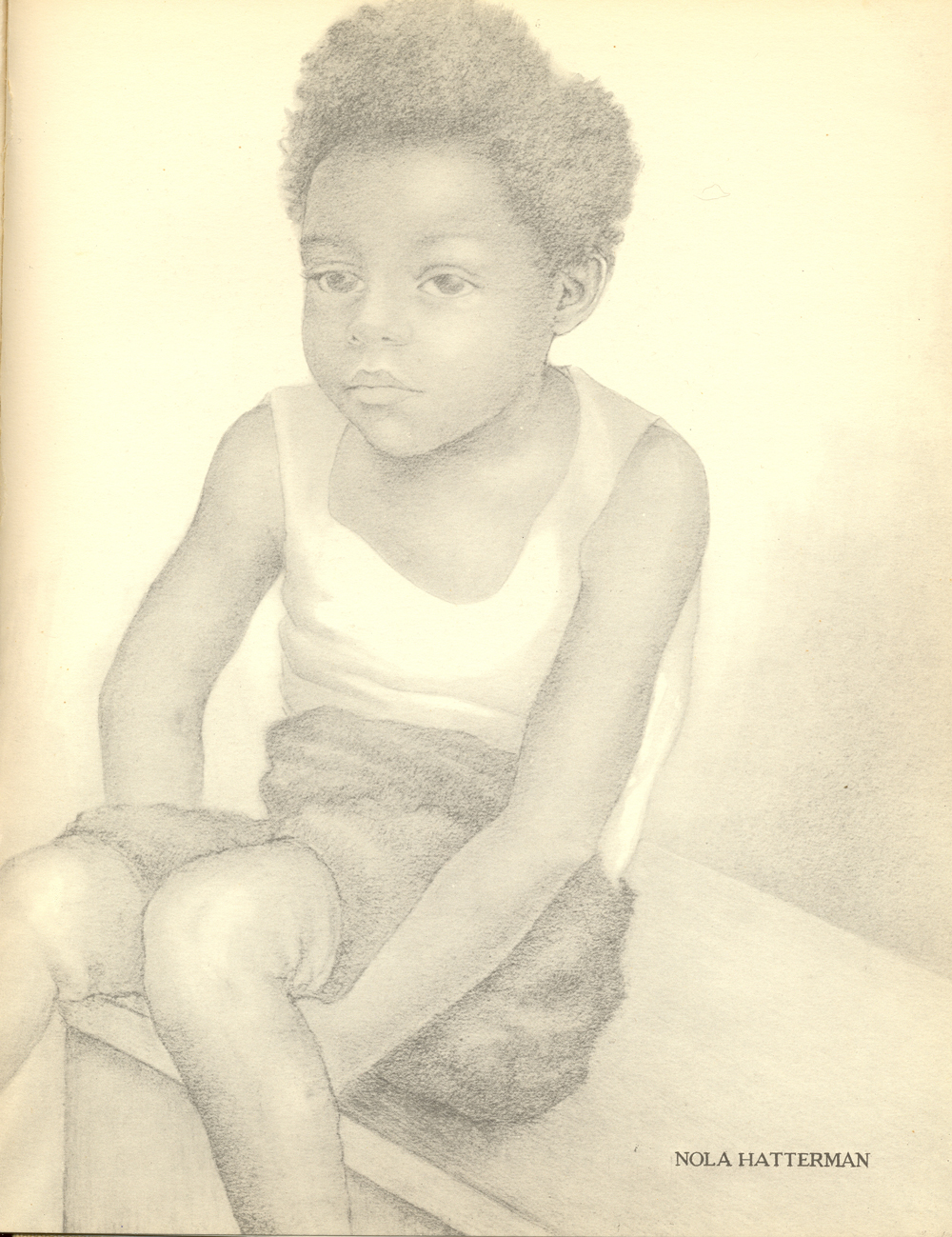

The flamboyant Nola Hatterman (1899-1984) came from a well-to-do, white colonial family. ‘That is the cause of my rebellion’, she stated later. Around 1930, overseas migrants (mainly Afro-Surinamese) were beloved painter’s models. For Nola they became the subject of her life. She propagated a black beauty ideal, fought against racism and supported young Surinamese students in Amsterdam in their search for their own, oppressed Surinamese culture.

Anti-colonial

She shared their commitment to independence of Suriname [in 1975 Suriname gained independence from the Netherlands] and emigrated to Suriname in 1953. As director of the School van Beeldende Kunst, School of Fine Arts, in Paramaribo, she was the teacher of many pupils. In time her teaching methods were criticised: old-fashioned. After her death however she was reinstated and praised for her contribution to Surinamese art. Reason why one of the art academies was named after her death in 1984: the Nola Hatterman Art Academy.

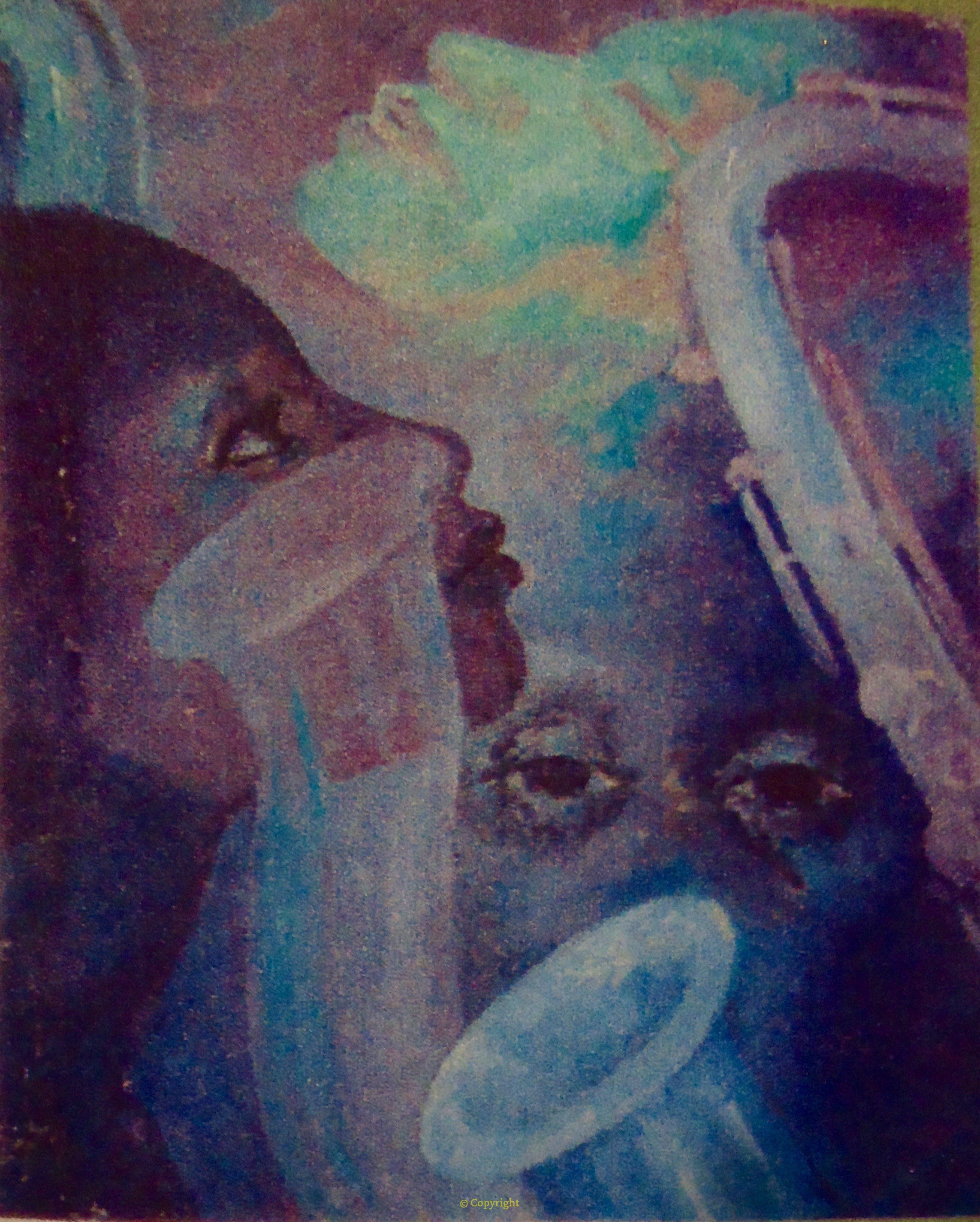

In the Netherlands Nola is less known. The recent purchases by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Museum Arnhem and Centraal Museum Utrecht of the paintings Girl, Trumpet player, Jazz, and the Black Pieta show growing interest in the artistic value of her work, of which the themes – migration, racism and decolonization – are even more relevant today. Part of her oeuvre is still untraceable or – as far as Suriname is concerned – not inventoried. The aim of this project is to track down her work and map it in a database.

BIOGRAPHY

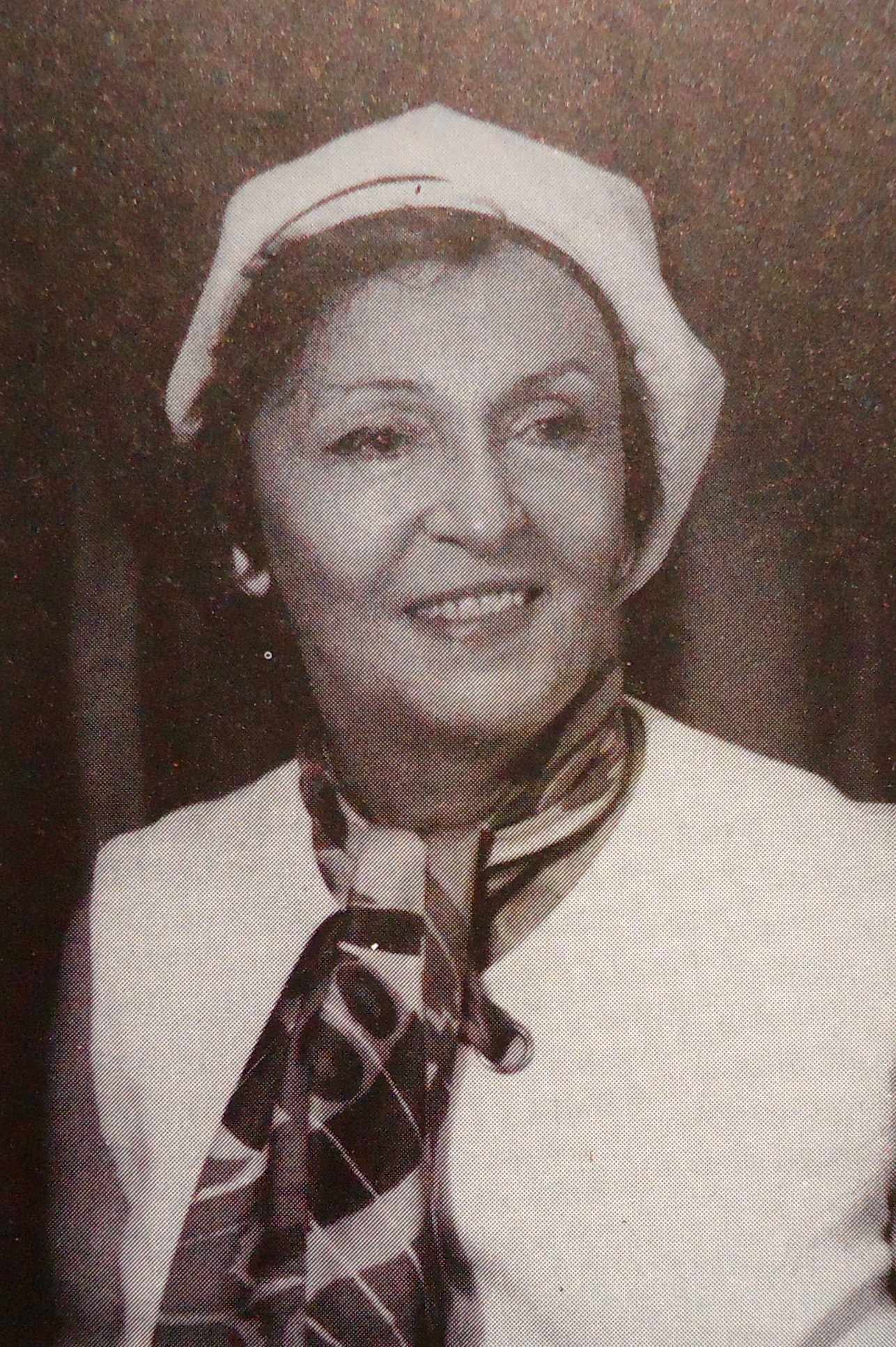

Nola Hatterman (1899-1984) ‘I come from a colonial environment. (…) That was actually the cause of my rebellion. ‘

Youth

Nola was born in Amsterdam. Nola’s father, John Hatterman, was an accountant at an ex- and import company in colonial goods from the Dutch East Indies. “My father worked at a coffee office, there you came into contact with everything that was colonial. Actually that was the cause of my rebellion”, she said as an adult. Rebellion against the established order became the guideline of her life. As a child she was surprised by the discrimination of the inhabitants of the overseas colonies. She thought they were beautiful and made friends with the children from the Dutch East Indies around her. In retrospect, she analyzed: “Of course, how can you suppress a country if you appreciate its inhabitants?”

Twenties and thirties

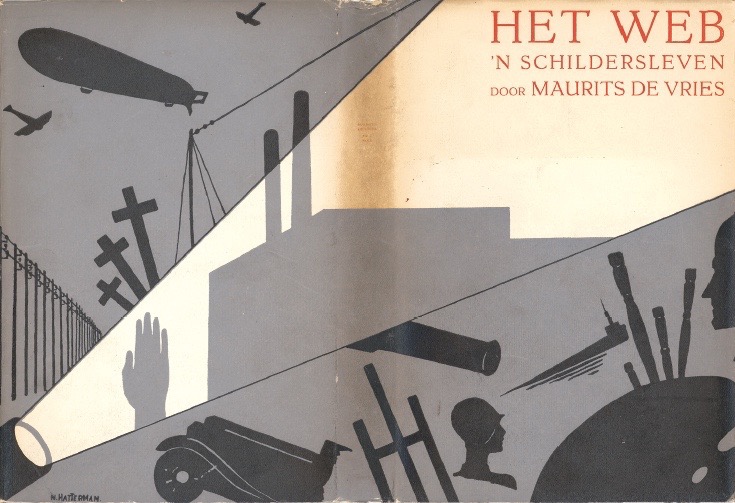

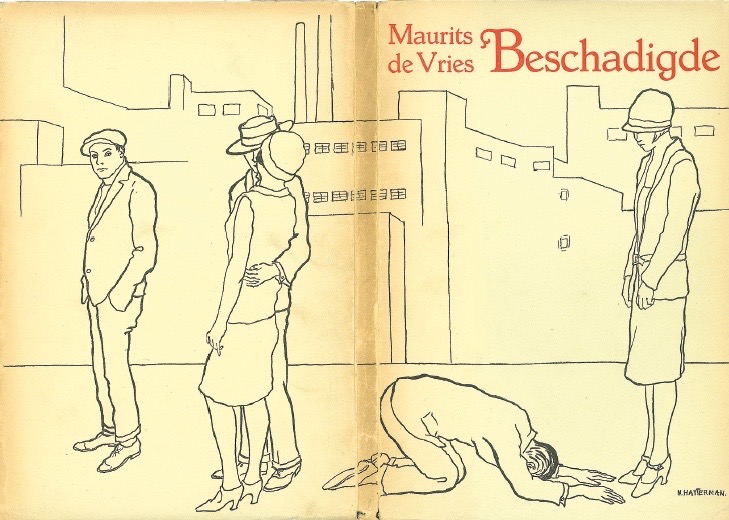

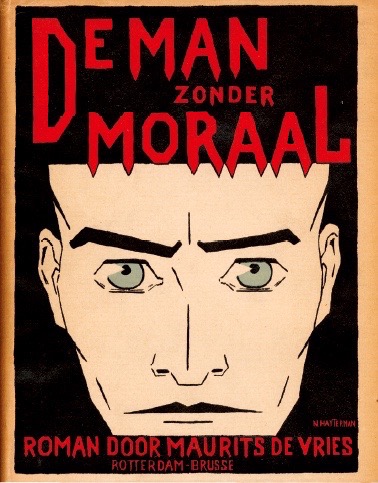

Nola left the grammar school early for the theatre school. She motivated that choice from the subordinate position of women. On stage, woman was equal to man, she thought. She graduated in 1918 and played with various companies in different pieces. She also figured in five films. In 1920 she was given a role in the popular music play De Jantjes. She fell in love with the director of the piece: the Jewish Maurits – Maup – de Vries, with whom she moved in when she was around 23 years old. Between the theater rehearsals she exhibited her first drawing in 1919 during the group exposition of the artists’ association De Onafhankelijken at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

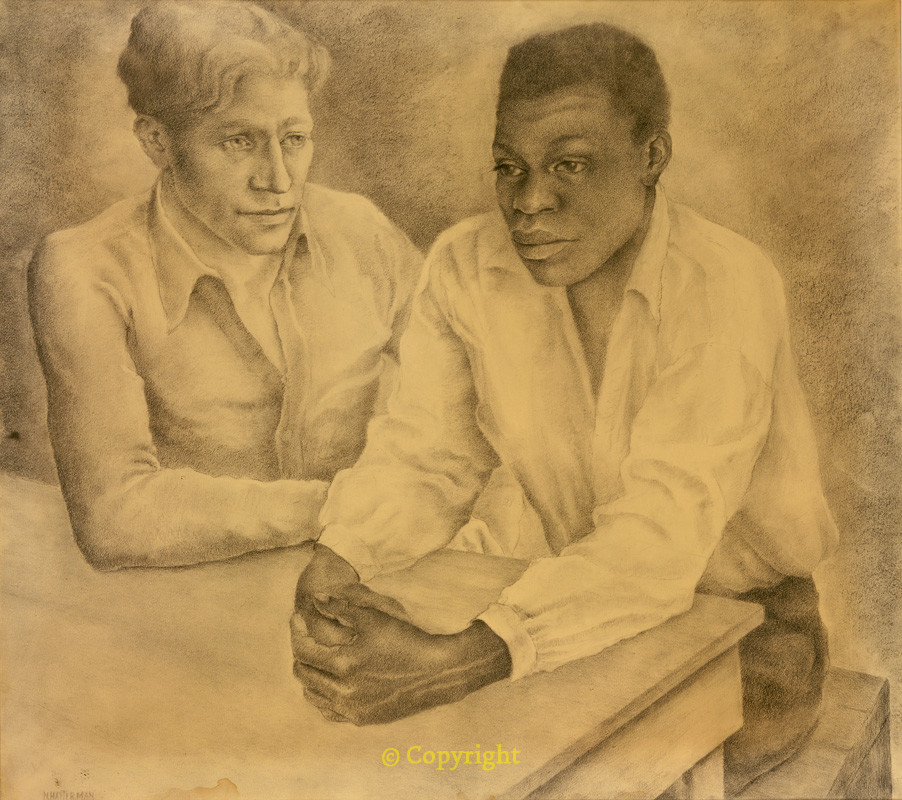

In 1925 she stopped acting to fully concentrate on painting. She presented her work mainly at artists’ associations (De Onafhankelijken, De Brug and Sint Lucas) and garnered both criticism – ‘bad drawing’ – and praise. The painting Op het terras, On the terrace (1930), which nowadays counts as her masterpiece, was already a sensation at the time. ‘The large portrait of the man in front of his café is, both in his expression and in his composition and color combination, a testimony to deep inner civilization and taste’, wrote the Algemeen Dagblad in the newspaper of 8 March 1939. Immigrants from the former colonies were at that time ’the painters’ novelty, both of other colour, and having other shadows and the highest light on their body,’ wrote the art critic Albert Plasschaert in the Groene Amsterdammer of 19 April 1930. Nola was not unique in her portraits of colored – especially black – people. Around 1930 Jan Sluijters was one the painters who was known for his portraits of black people, one of his favorite models was Tonia Stieltjes (daughter of a Dutch mother and a Surinamese father). Unique was her friendship with and commitment to the overseas immigrants. Her house at Falckstraat in Amsterdam was an open house, leaving room for a long line of tenants, often Surinamese, who moved in, such as the colorful Prince Kaya, alias Johan Vroom. Black tenants were not welcome everywhere.

Around the Second World War

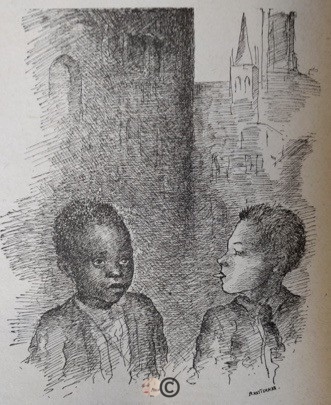

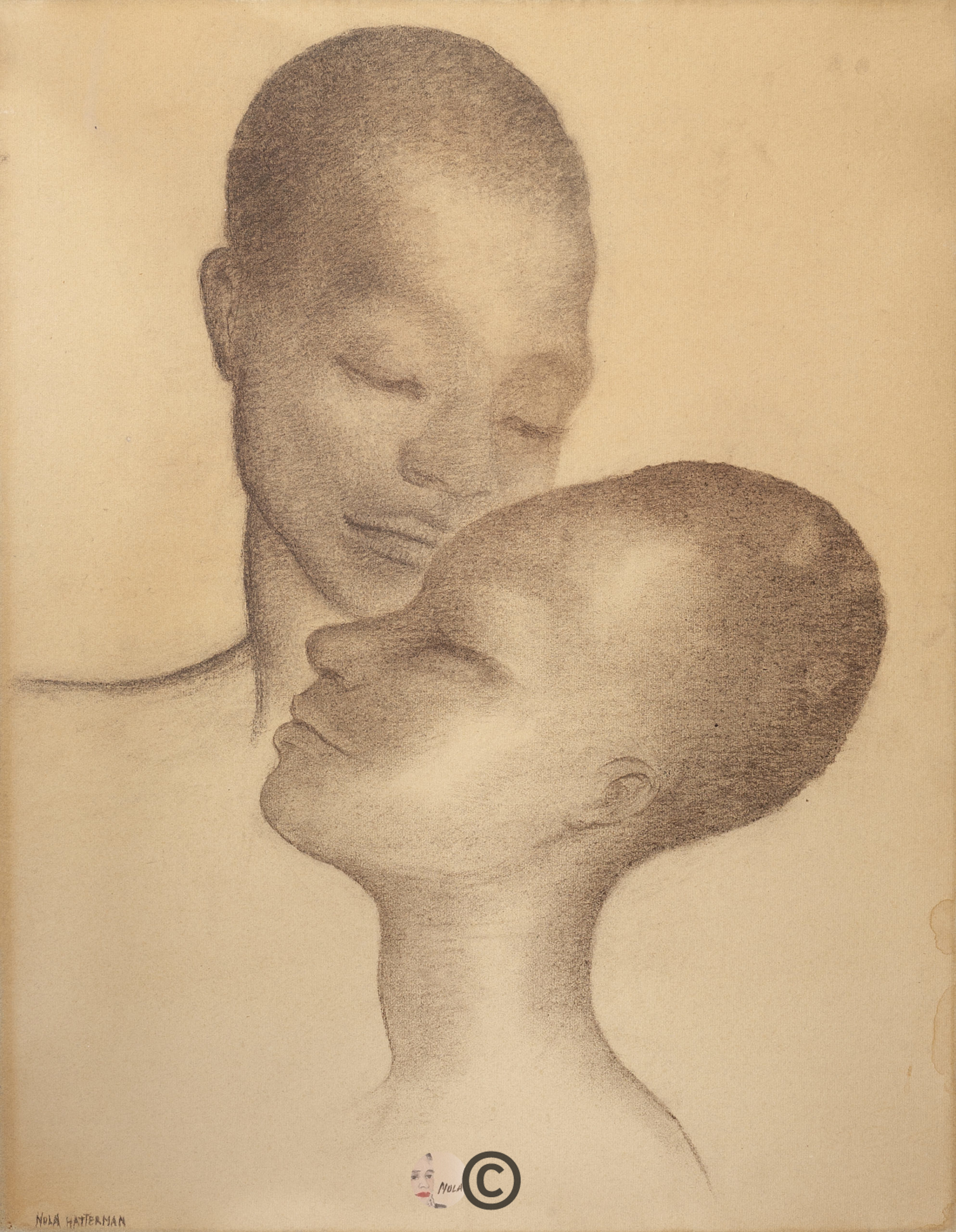

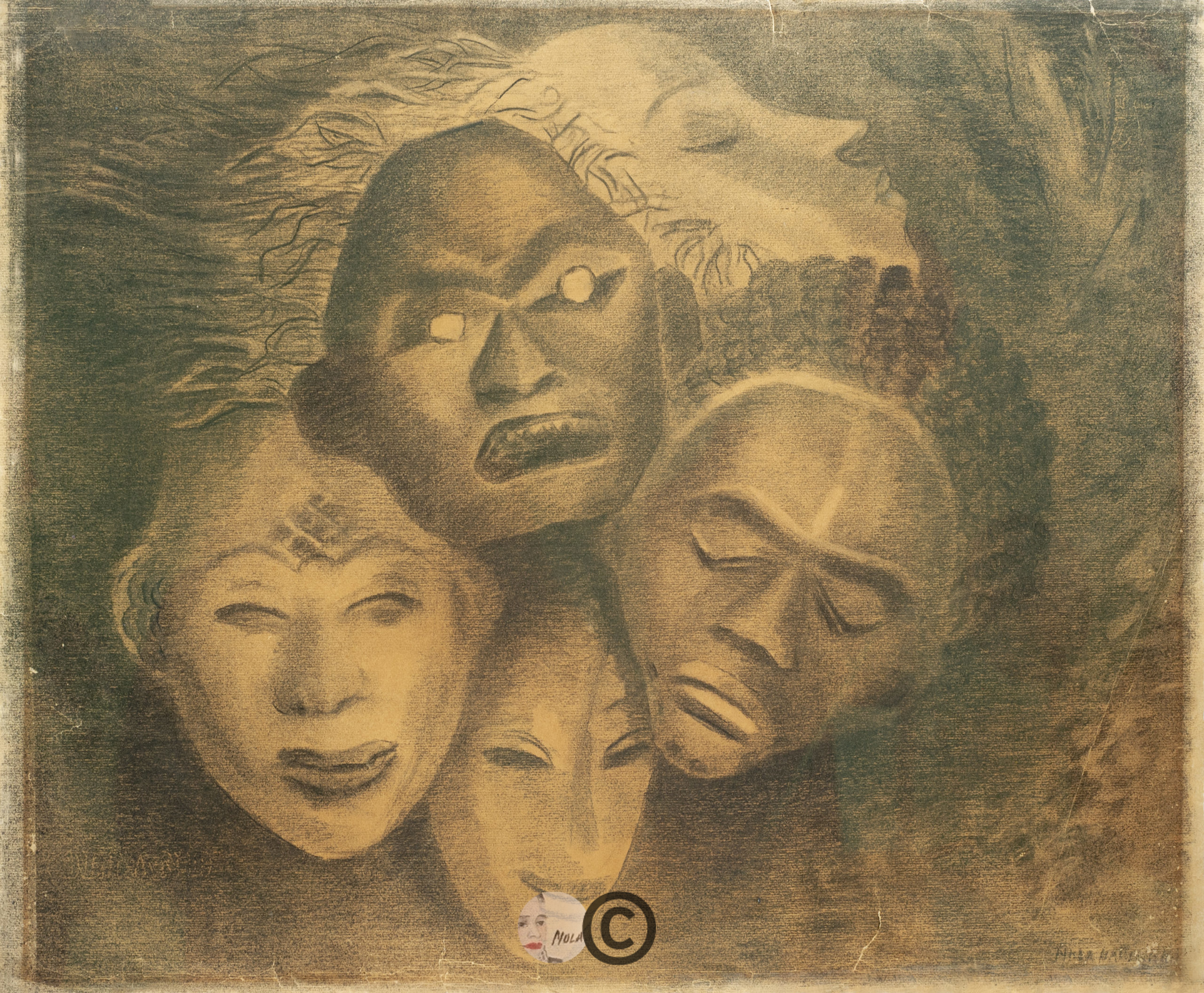

Nola married Maup de Vries in 1931. Because of Maup’s Jewish background, the De Vries-Hatterman couple followed the developments in Nazi Germany with suspicion. It joined the ‘World Committee of Artists and Intellectuals for the Victims of Hitler Fascism’ and ‘The Association of Artists in the Defense of Culture’ (abbreviated in Dutch as BKVK). In 1936 The BKVK organized a remarkable exhibition in Amsterdam under the title: De Olympiade Onder Dictatuur, The Olympiad Under Dictatorship (abbreviated as D.O.O.D. : D.E.A.D. in English). It was a flaming protest against the curtailment of free art by the Nazis during the Art Olympiad – a competition in the fine arts – which took place in Berlin. With her drawings, Nola challenged Hitler’s ideas on ‘racial purity’.

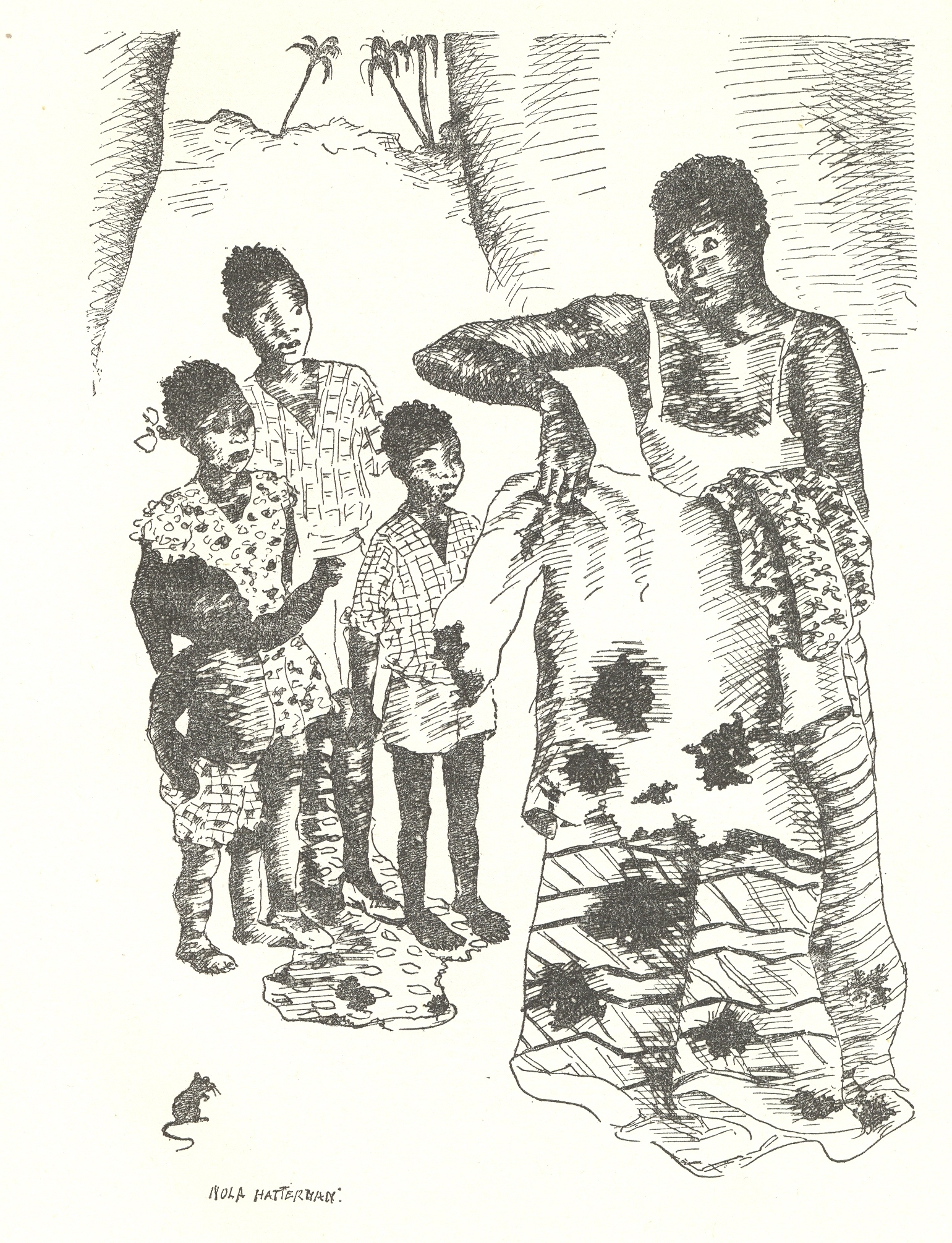

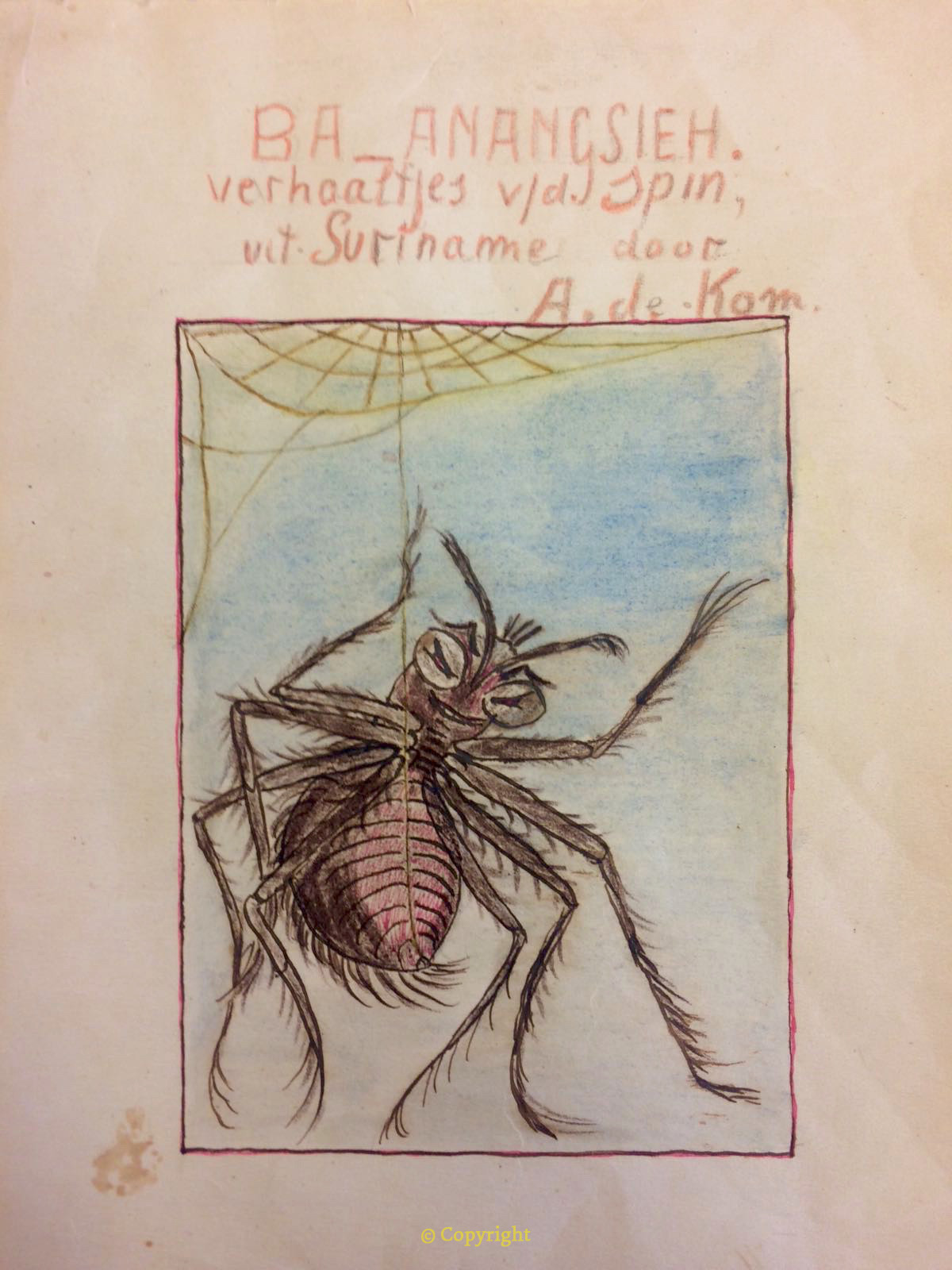

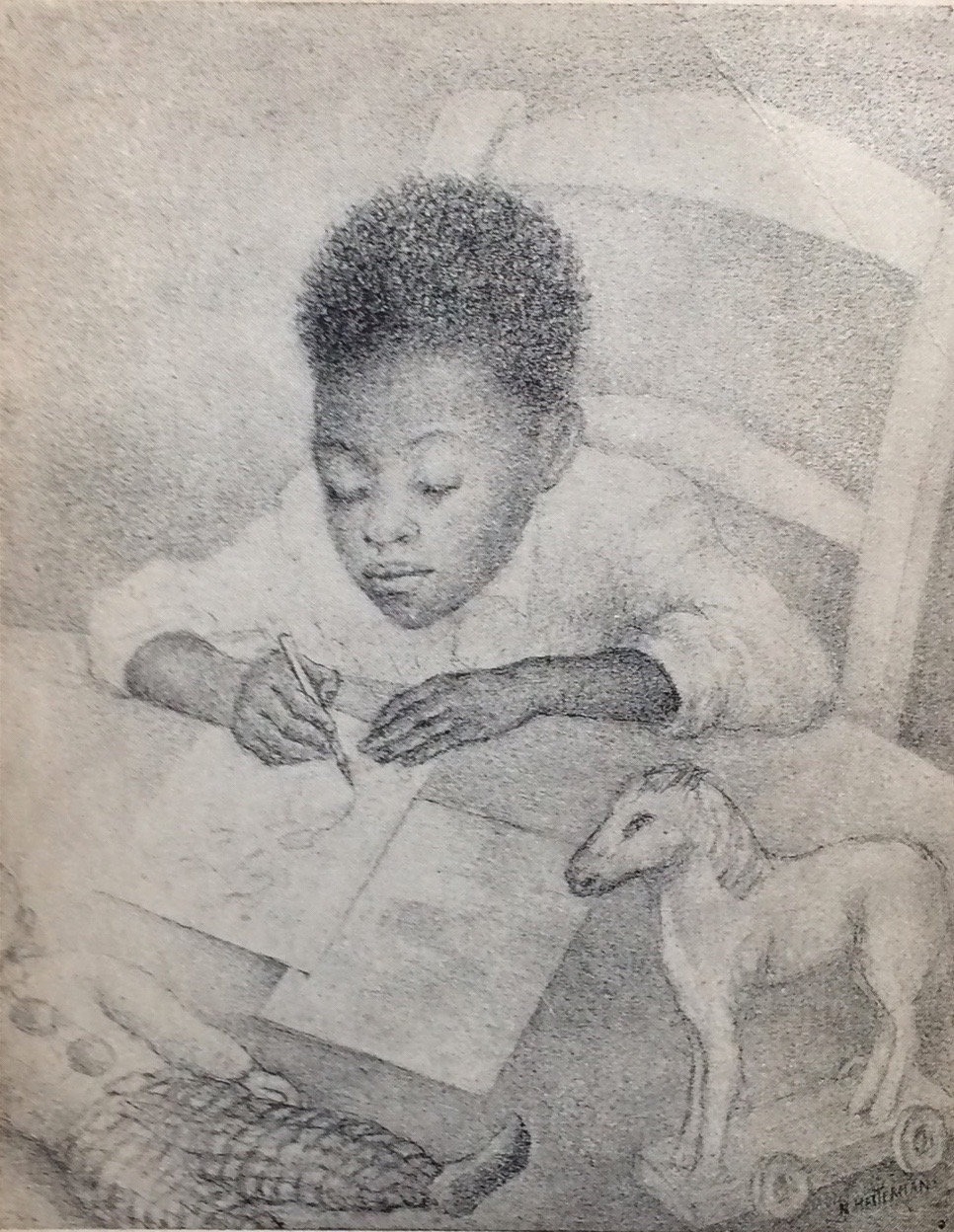

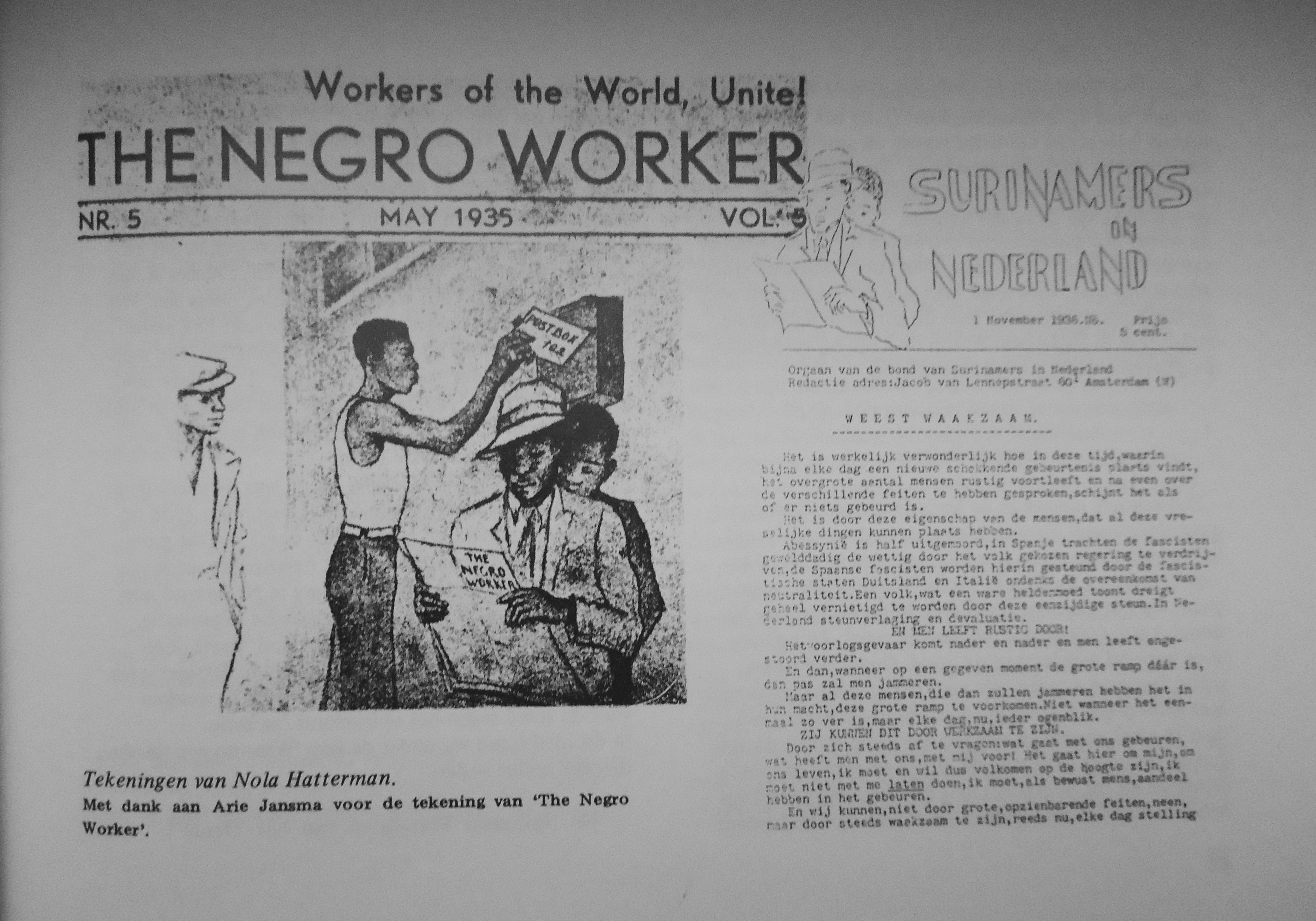

Her marriage to Maup did not last long. Nola fell in love with visual artist Arie Jansma: convinced communist and active in the resistance against fascism and Nazi Germany, just like members of the Federation of Surinamese workers in the Netherlands. Through Arie, Nola probably came into contact with this anti-fascist Surinamese labor movement and Surinamese communists such as Otto Huiswoud and Anton de Kom: the first anticolonists. She drew illustrations for the union magazine of the Association of Surinamese Workers in the Netherlands and the forbidden – because: communist – organ of the international black workers’ union, the Negroworker (sic!). During the war, Nola refused to register with the Kultuurkamer, set up by the Nazis. Her propaganda for a black ideal of beauty was at odds with the German hymn on the blonde, blue-eyed ‘Aryan race’.

It is ironic that five months before the establishment of the Kultuurkamer the NSB official agreed to purchase Nola’s lithograph of Surinamese folk dance – dancing negroes (sic!). Presumably only the adjective ‘dancing’ was noticed. Note: At that time, the word ‘negro’, also used by Afro-Surinamese people, did not have the negative connotation it has today. Here the term used, is: Afro-Surinamese or black. In historical quotations the original style has been maintained.

After the war

After the war Nola and her life’s partner Arie mourned the loss of murdered resistance comrades – including Surinamese as Anton de Kom – and their Jewish artist friends who never returned from the camps.

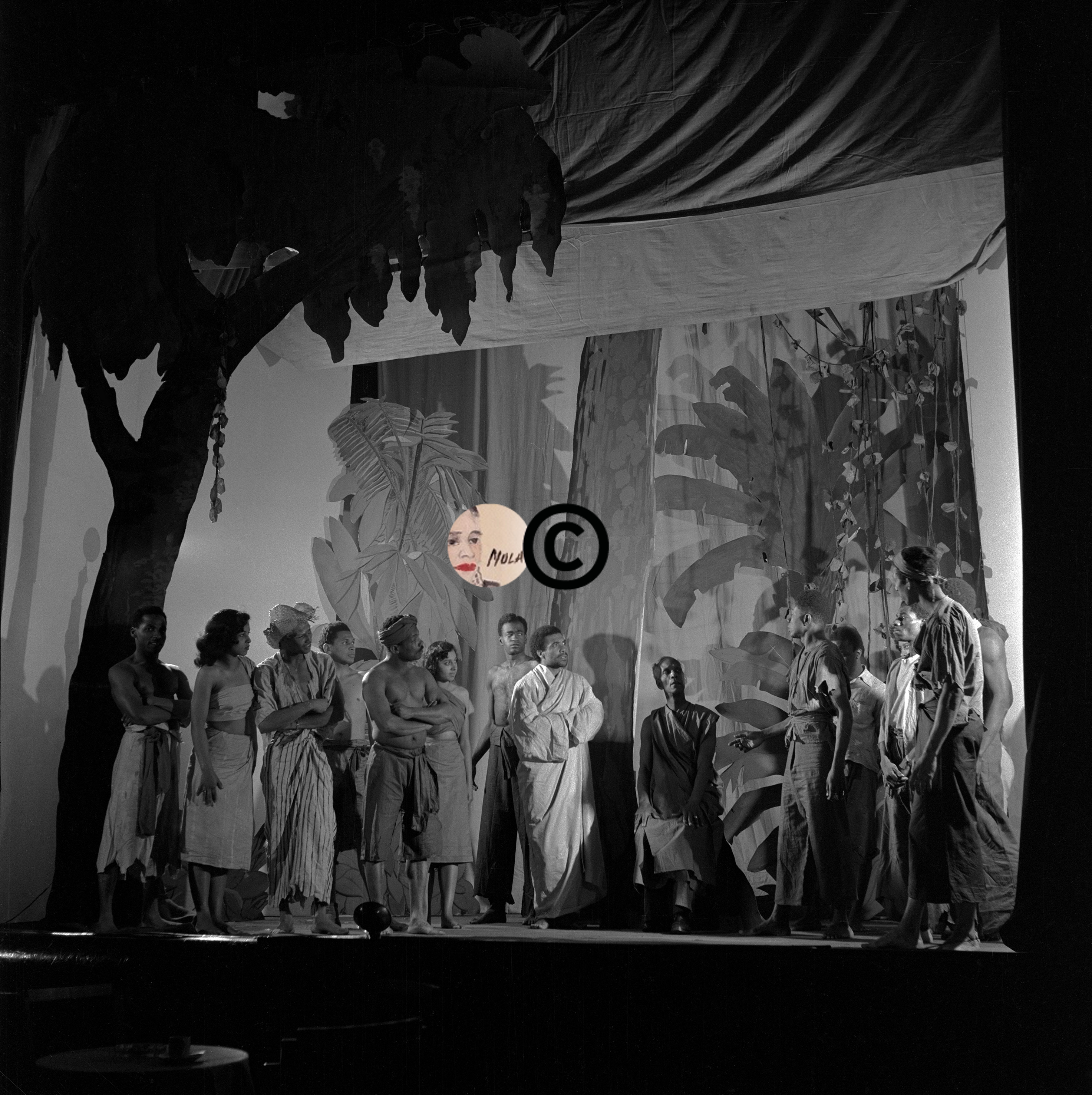

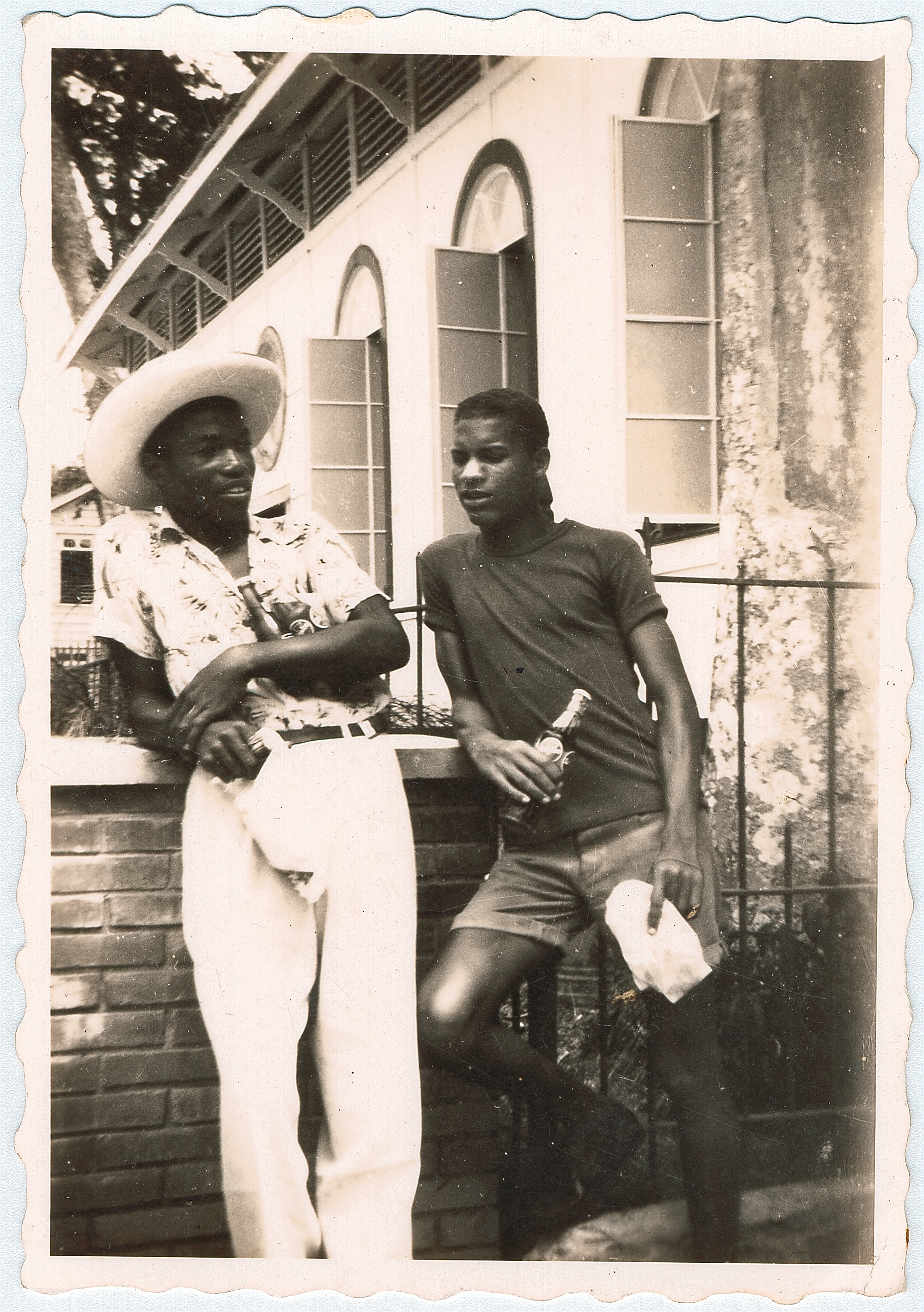

A new group of Surinamese came to the Netherlands after 1945 for study purposes: mostly boys from the dark-colored folk class. Under their leadership, The Vereniging Ons Suriname (VOS) in Amsterdam, transformed from a social club into a stronghold pleading for decolonisation of Suriname. Their members founded the Who Eegie Sanie movement (Surinamese for Our own things). Their search for and reappraisal of their own – oppressed – culture fits seamlessly into Nola’s aim to capture the beauty of the black people on canvas. One of the men who attended the meetings of the VOS and Wie Eegie Sanie and who would play an important role in the political relations in Suriname, was the later Surinamese former prime minister Jules Sedney. He admired Nola for her involvement with the black Surinamese in Amsterdam. Nola’s group portrait After Fesie – de Toekomst – members of Wie Eegie Sanie who participated in the play The Birth of Boni on the black 18th century Surinamese freedom fighter Boni. The piece symbolized a free and independent Suriname. The nationalist Eddy Bruma (1925-2000) wrote the piece. The black cast consisted of Otto Sterman, Frits Pengel, Imro Kambel, William de Vries, Hugo Overman, Hugo Kooks, Hein Eersel, Paula van Wijk and Prins Kaya. Nola designed the decors.

After the war, realism, the art movement to which Nola belonged – was dismissed in the Netherlands. As was the interest in black painters’ models, although new, abstract art movements had discovered African culture as an exotic painter’s object. Nola rejected this exoticism, she portrayed black people as members of contemporary European society. For Nola, black people had become the subject of her life. It is not surprising that she was looking for new horizons since her work was no longer appreciated in the Netherlands. In 1953 she left for Suriname by boat. The group portrait Na Fesie stayed behind in her studio. On the collar of one of the actors involved in the play, she brushed: ‘Not finished, left for Suriname’.

Suriname

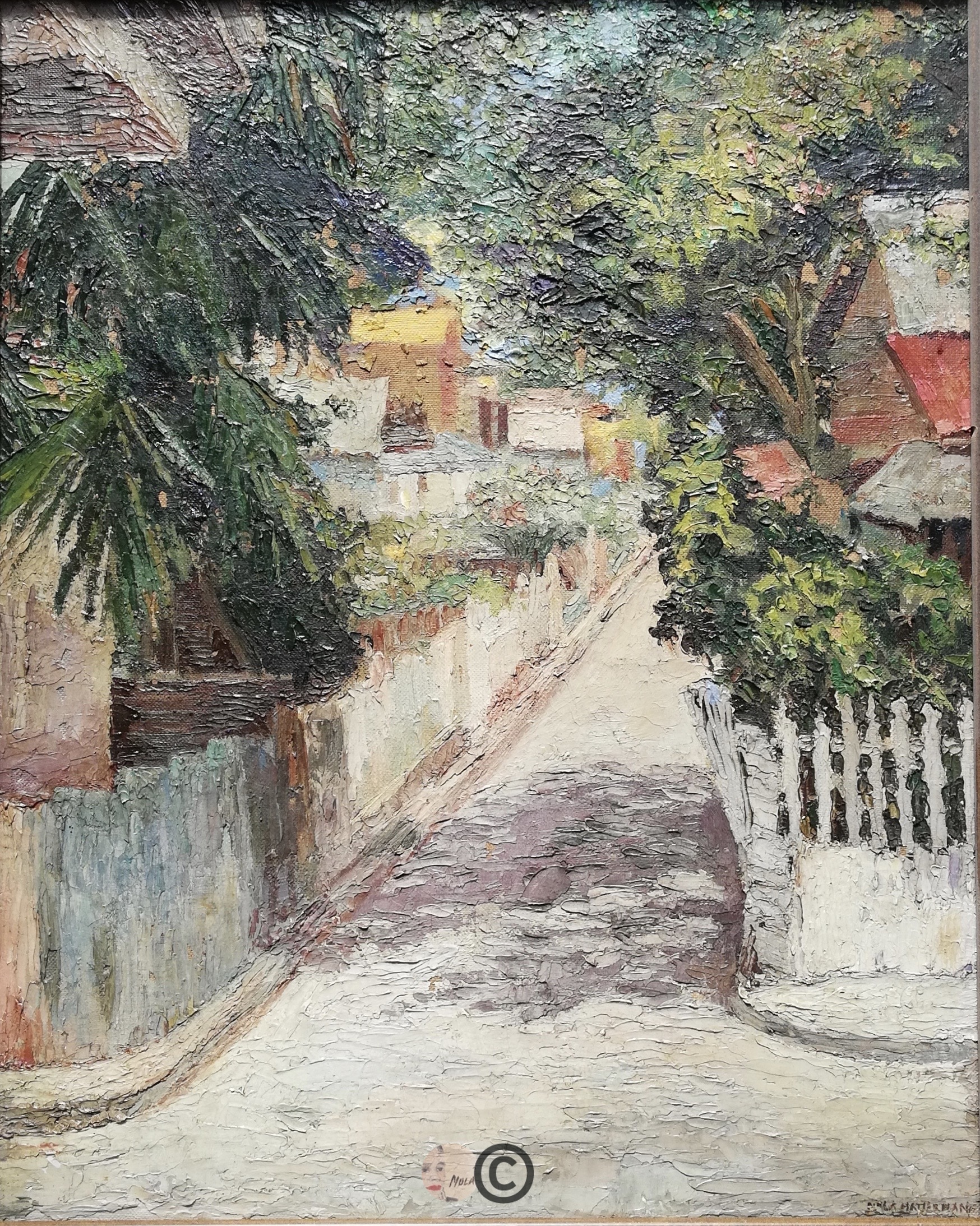

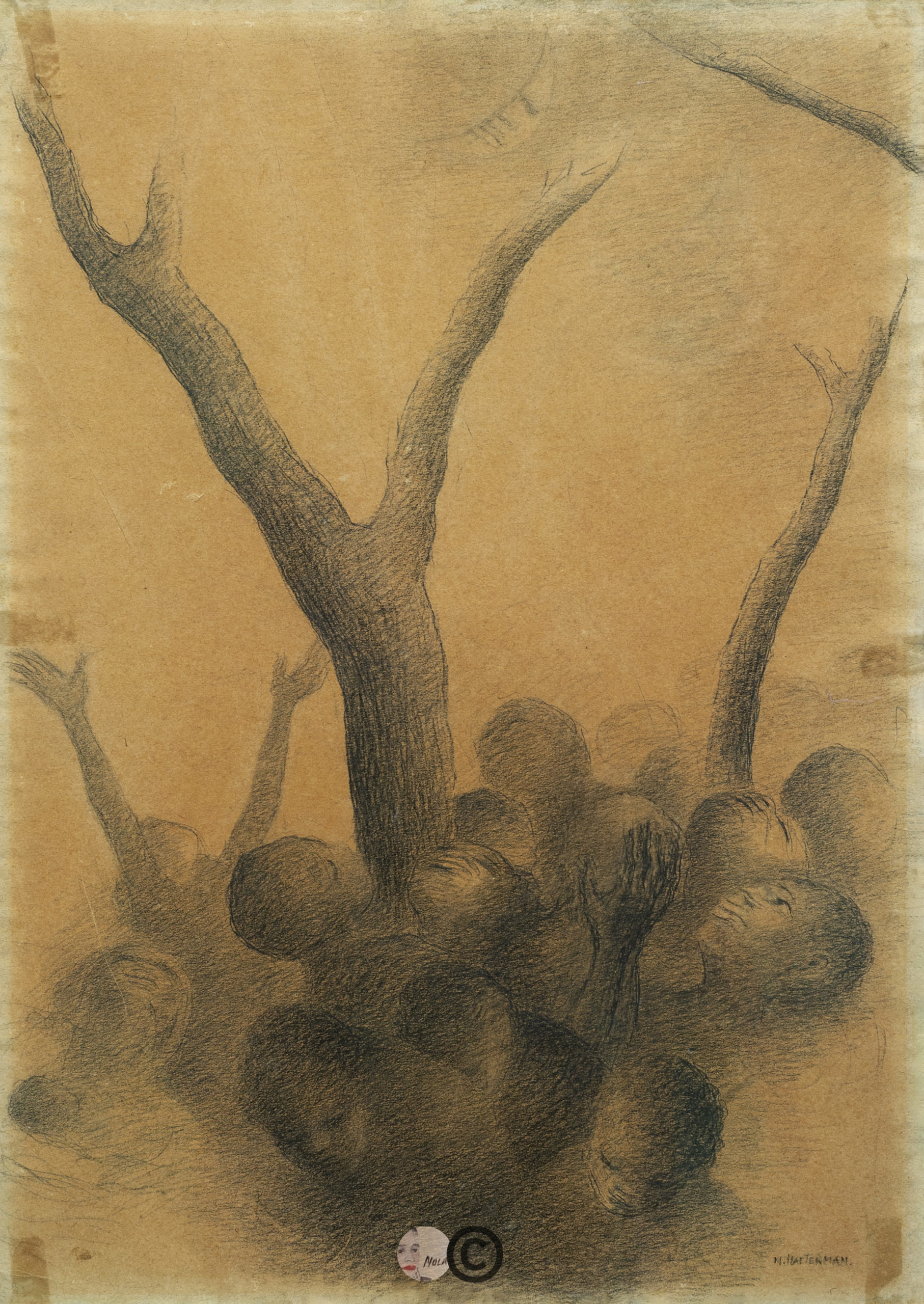

Initially, Nola was not welcome in Suriname because of her communist sympathies. Nevertheless she was asked to take charge of the drawing course of the Cultural Center Suriname (CCS). In 1960 the course was extended to the School for Visual Arts, of which Nola became director. The school delivered countless artists who went to the Netherlands to continue their study. Nola came to see that they were being ‘ruined’ there. She concluded: Suriname must develop its own national art and stop modelling itself on Europe. Around 1970 her teaching methods came under fire: one-sided and old-fashioned. Moreover, the young generation – inspired by the black power movement and Frantz Fanon’s The wretched of the earth – asked themselves why a ‘foreign’, Dutch instead of Surinamese school principal? Nola was shocked; she felt Surinames and ‘black’ inside. She moved to the interior of Suriname, Brokopondo, to finish her historic fourth-panel on slavery and resistance (marronage). Thus she completed the assignment she had set herself, after reading Anton de Koms Wij slaven van Suriname, We slaves of Suriname, to paint the Surinamese heroes who revolted against colonial enslavement, such as the 18th century Boni did.

In 1984 Nola was killed in a car accident when she was on her way to a group exhibition in Paramaribo. Her funeral went exactly as she wished in her poem Wan de (One day): ‘One day I shall die. Surinamese ground will receive me. Black hands will bury me.’ And so it happened. Surinamese dragiman danced her coffin to her grave at the Schietbaanweg in Paramaribo on the copper tones of the music.

WORK

Nola Hatterman is best known as a visual artist (and less as an illustrator), but she served several muses. She started her career in 1918 as a (film) actress, chose a career as a painter in 1925 and later made occasional trips to literature. Many of her artworks have been lost. It is suspected that work has not been described. If you are acquainted with (still unknown) work of her, please make it known via the forum or send an email.

Visual arts

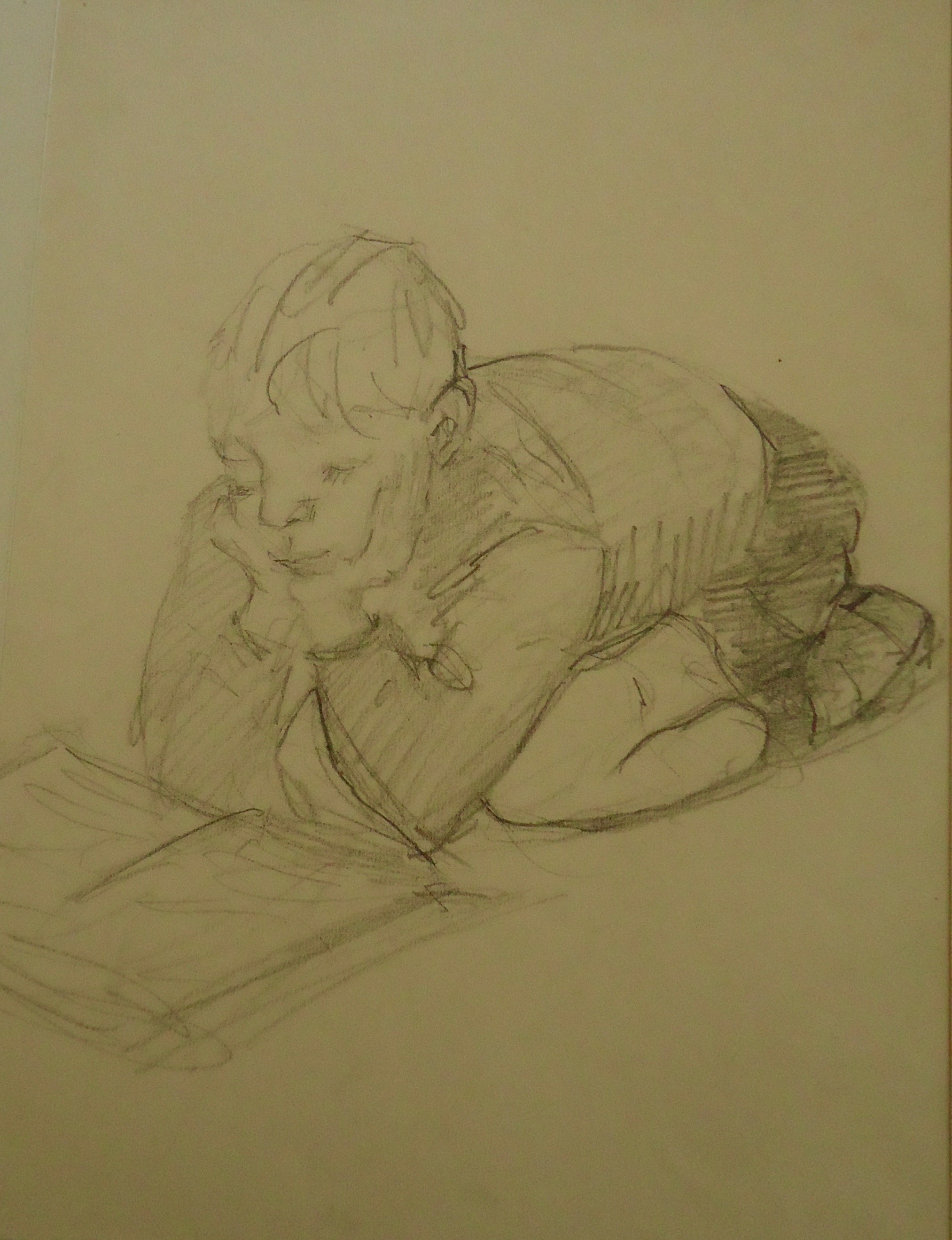

Nola’s formation as an artist

The irony is that Nola Hatterman – director of the art academy in Paramaribo – never visited an art academy herself. She received her education from private teachers from her teens. Her first teacher was the Italian painter Vittorio Schiavon (1861-1918). He taught her ’the fine Italian watercolour technique’. At the drama school (1915-1918) she followed drawing lessons from the painter Gerrit Willem Knap. Between the theater rehearsals she made her debut in 1919 as member of the artists’ association De Onafhankelijken in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. After Schiavon died, Nola took private lessons from Charles Haak: teacher at the Institute for Applied Arts in Amsterdam (forerunner Rietveld Academie). She praised his lessons: “I had private lessons from Charles Haak for three years (…) I learned as much from perspective, anatomy and art history as they now ask for a Middle Education Diploma.” After that, the painter Harmen Meurs became her teacher.

Exhibits before the Second World War

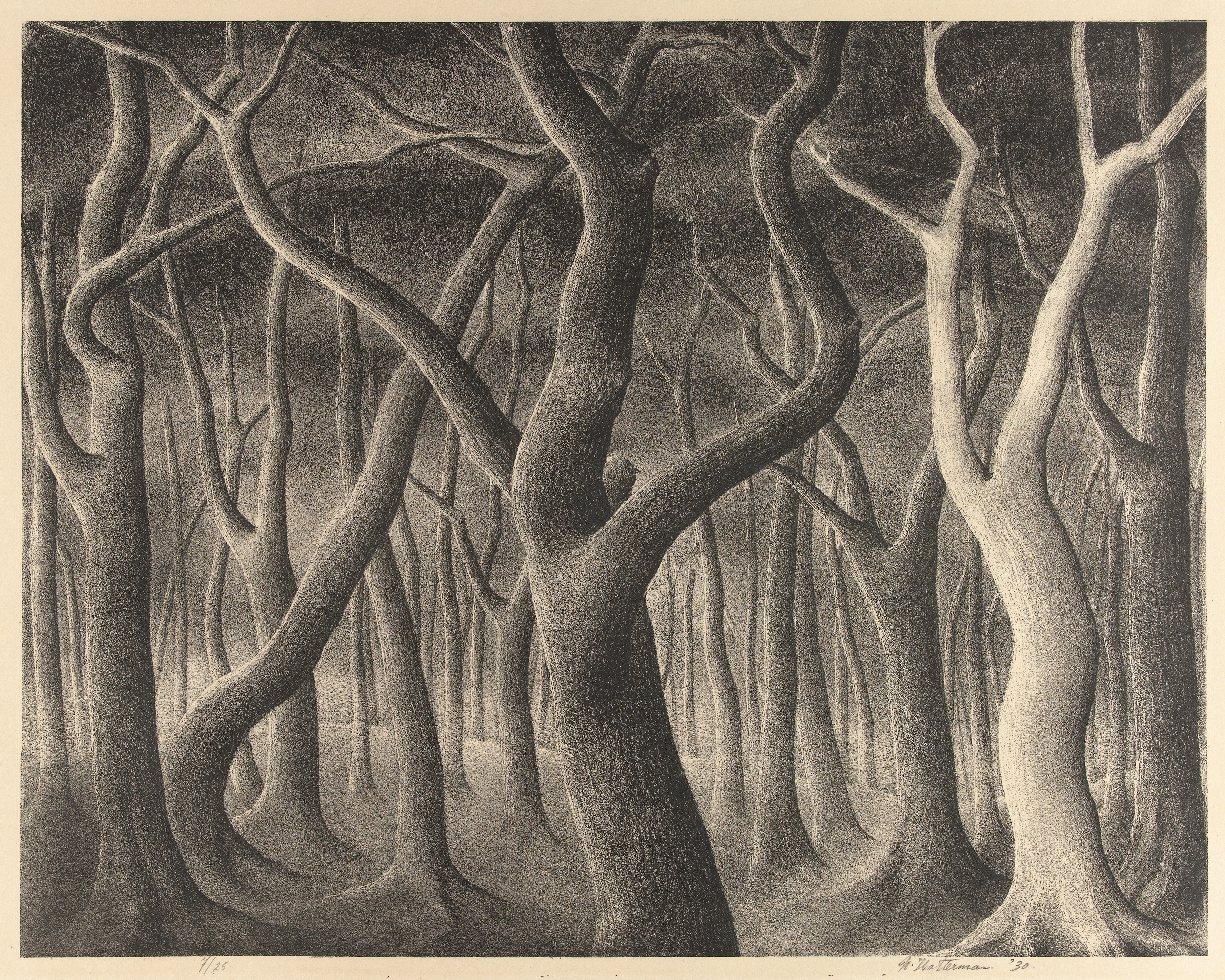

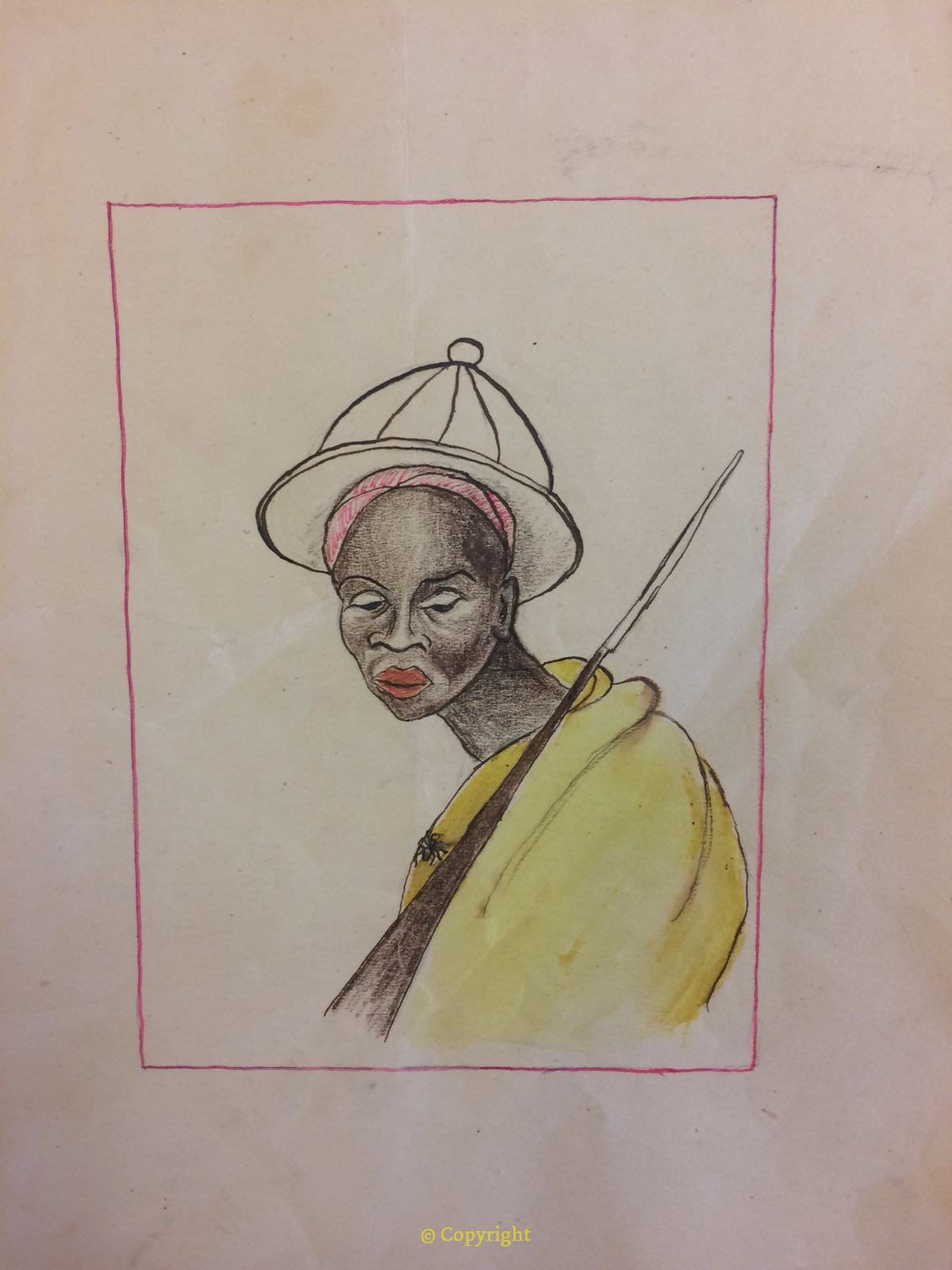

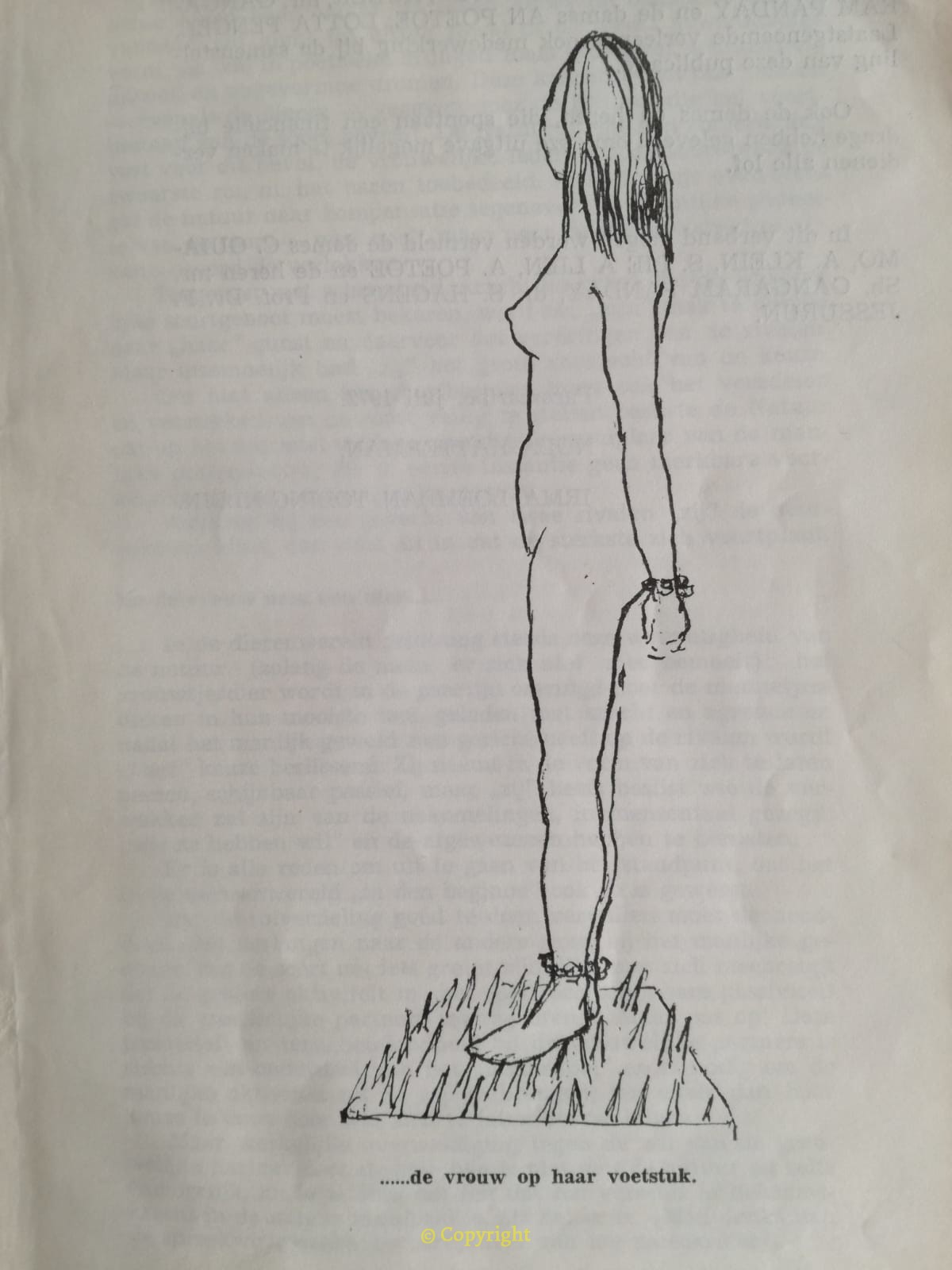

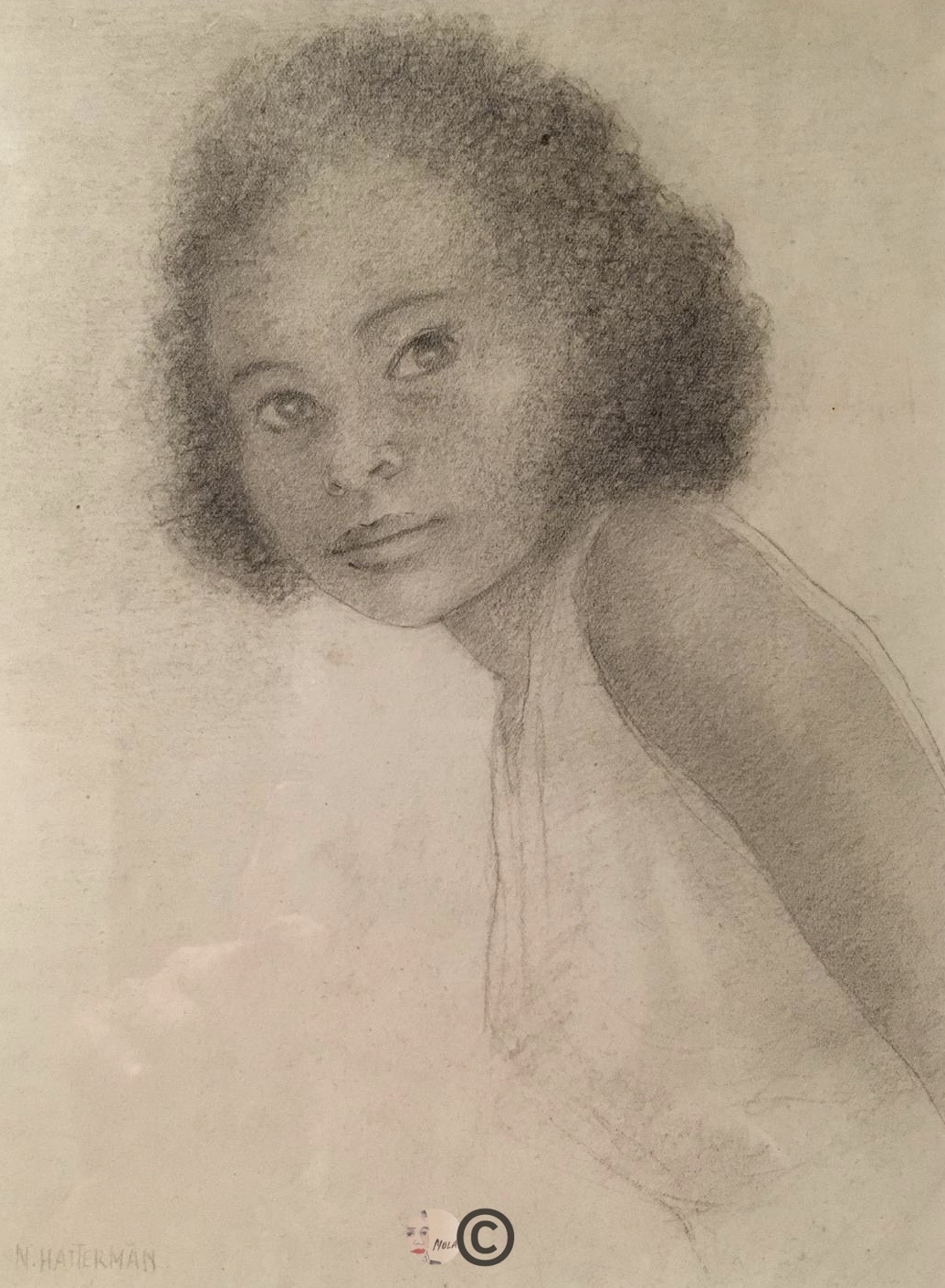

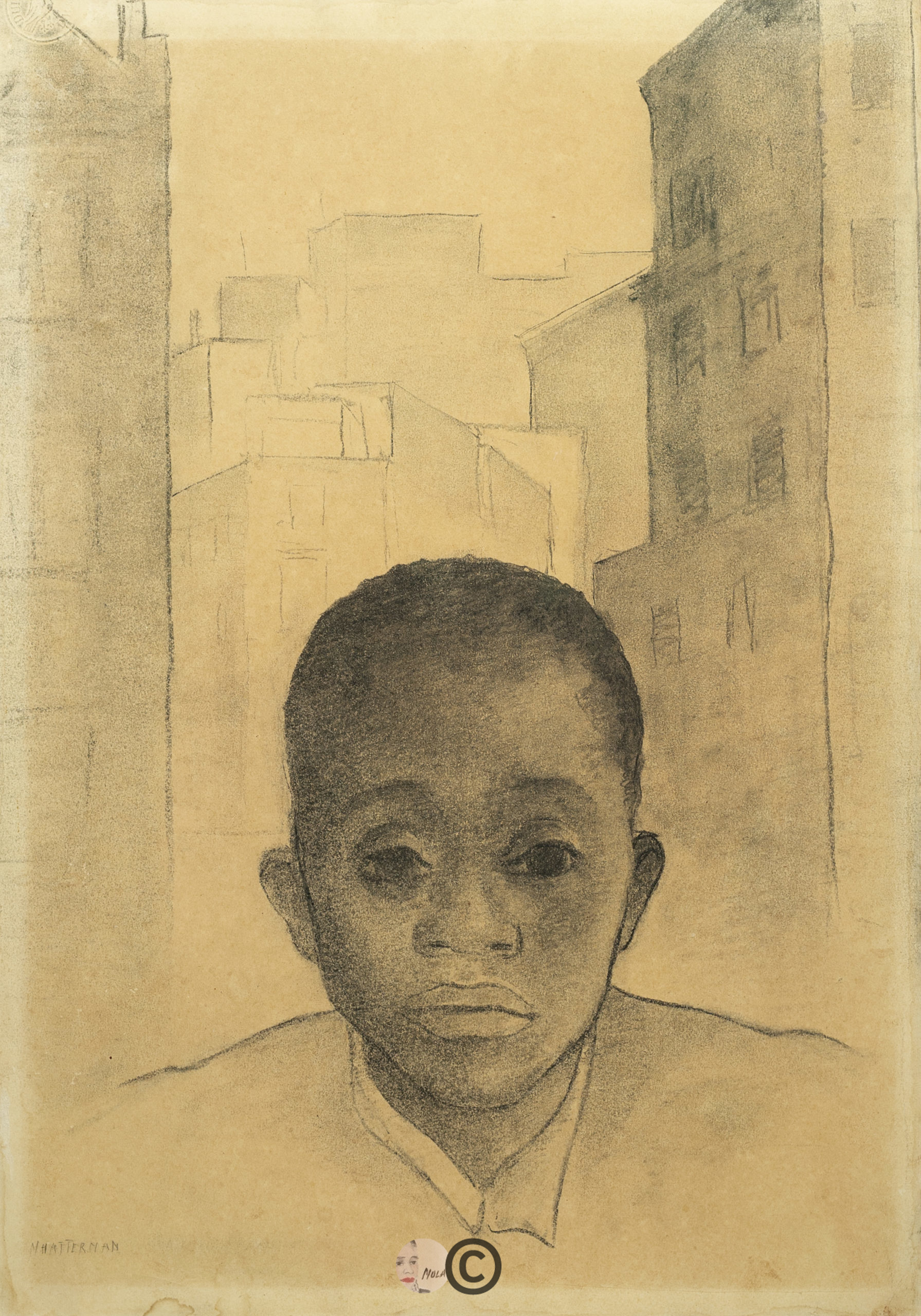

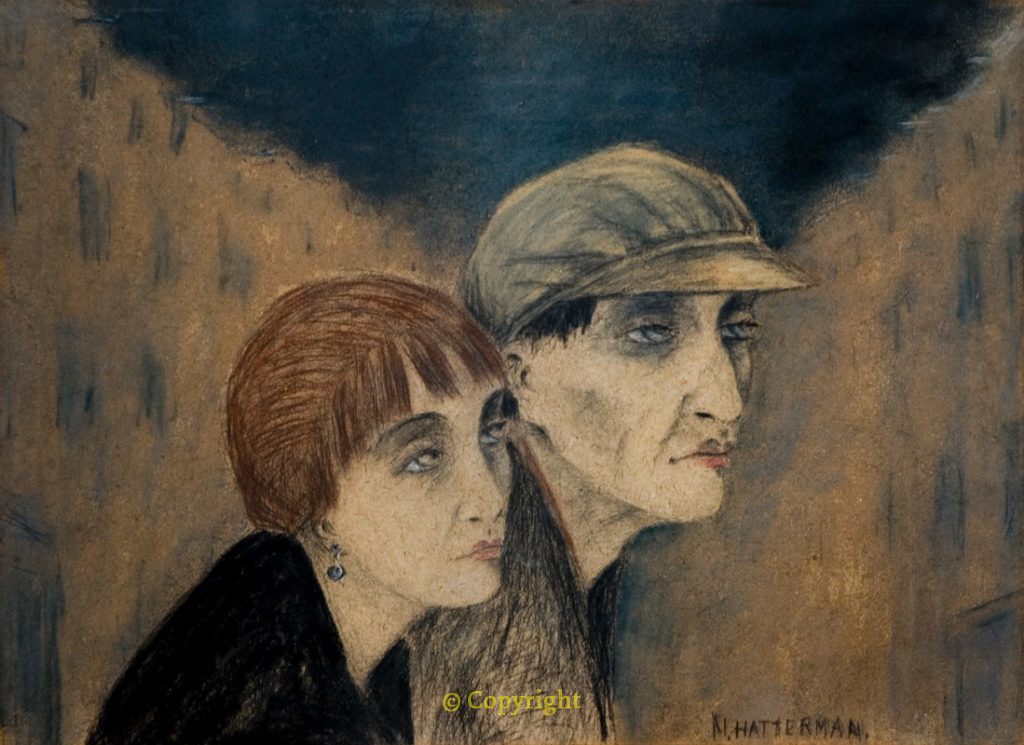

Between 1919 and 1941 Nola showed her paintings and drawings mainly in group exhibitions of the artists’ associations De Onafhankelijken (from 1919), Sint Lucas (from 1927) and De Brug (from 1930). Mostly in Holland. In 1938 she sent te oil paintings Nu and Sour d’été to the exhibition in Paris (as a member of De Onafhankelijken). In the 1930s she became a member of the World Committee of Artists and Intellectuals for the Victims of Hitler Fascism and the Association of Artists in the Defense of Culture (abbreviation in Dutch: BKVK). In 1936 the BKVK organized in Amsterdam the high-profile exhibition: The Olympiad Under Dictatorship: a fierce indictment against the censored Olympic Games in Nazi Germany. Participating artists included Paul Citroen, Peter Alma, Charley Toorop, Harmen Meurs, Chris Beekman, John Rädecker, Henk Henriët and the photographers Cas Oorthuys and Eva Besnyö. In three drawings – including a similar one as shown below – Nola criticized Hitler’s racial doctrine of the Aryan ideal of beauty: white, blond and blue-eyed, and the mother ’s role given to women.

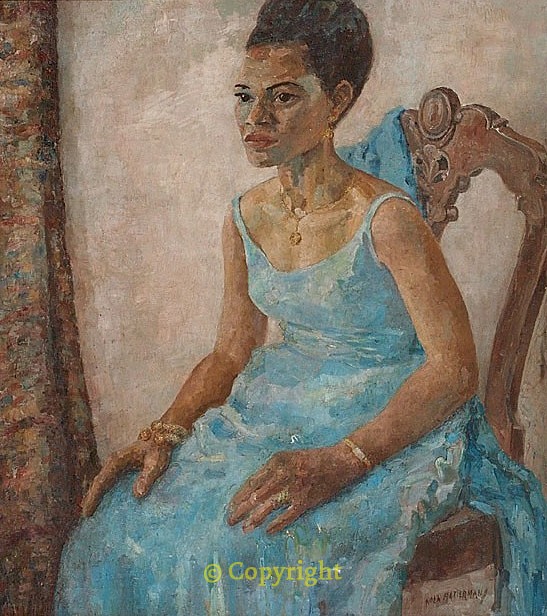

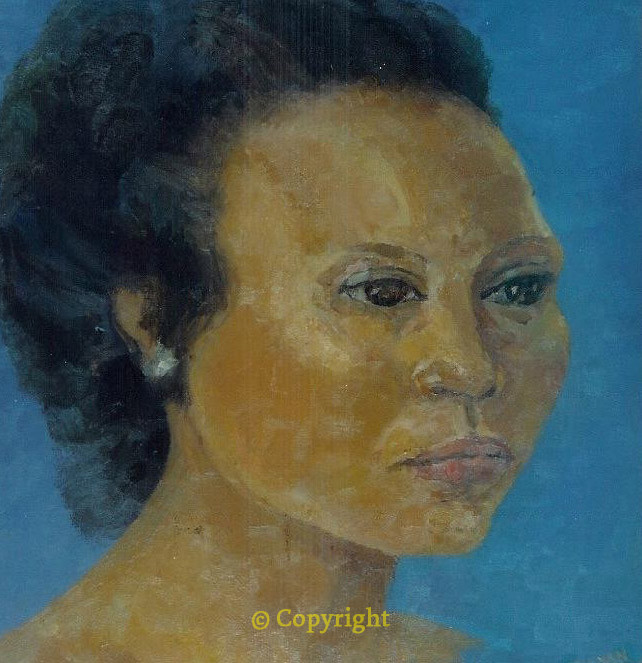

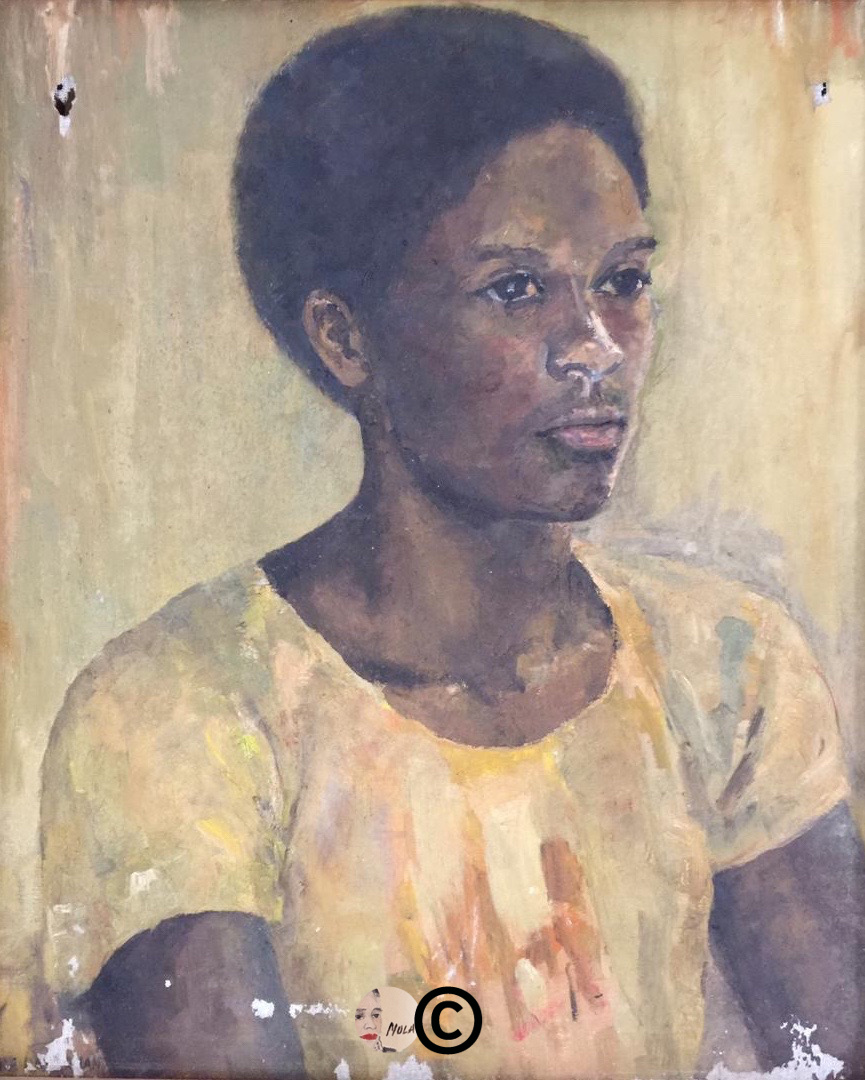

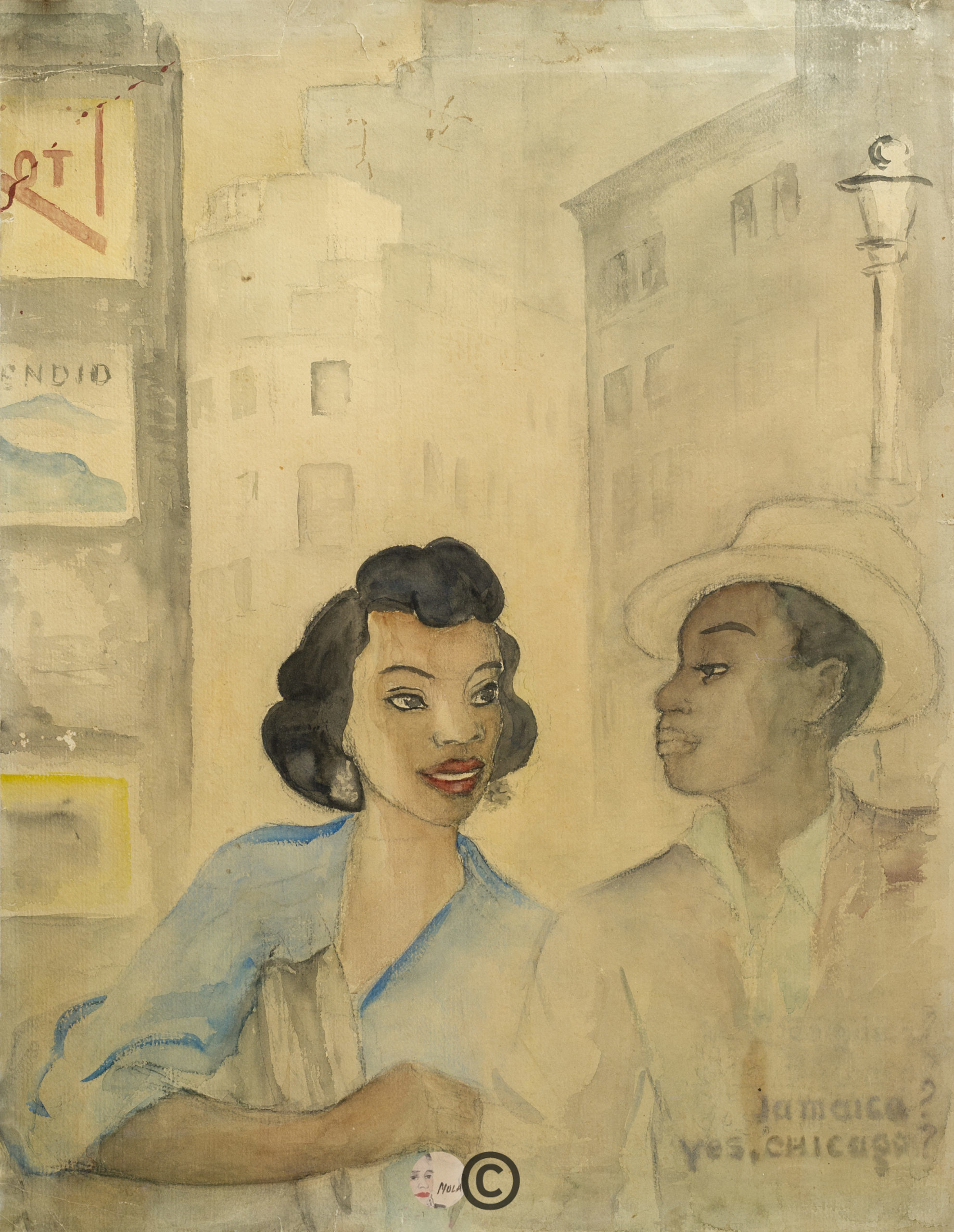

In 1939 Nola had her first solo exhibition at the Vereeniging Oost and West in the Victoria Hotel opposite the Central Station in Amsterdam with mainly portraits of mostly black people. To the question of journalists about her preference for ’the black man’, Nola replied: ‘I want to show black people in all their individual shades (…) engaged in modern society’. The critic of the Algemeen Dagblad wrote in the review of 8 March 1939: ‘We never saw work by Nola Hatterman before; therefore can not judge whether her work shows an upward trend. But we can certainly deduce from the exhibits here that we are dealing with a painter of talent who, even if she chooses a different subject, has a good future. She has the patience, the artistry of the born artist; taste and civilization and psychological insight in so great a degree that she can be counted among the good painters. ‘ Shortly after WW 2 broke out Nola refused to join the Kultuurkamer, which was set up and controlled by the Germans. That implied that she could no longer exhibit. It is unclear how exactly she earned her living; she sold a number of paintings to the Stedelijk Museum and the Tropenmuseum and in 1943 she was commissioned by the Amsterdam physician Bob Klokke to make a portrait of his wife Rinia Klokke-Moll (now in ownership of Tropenmuseum).

After the war

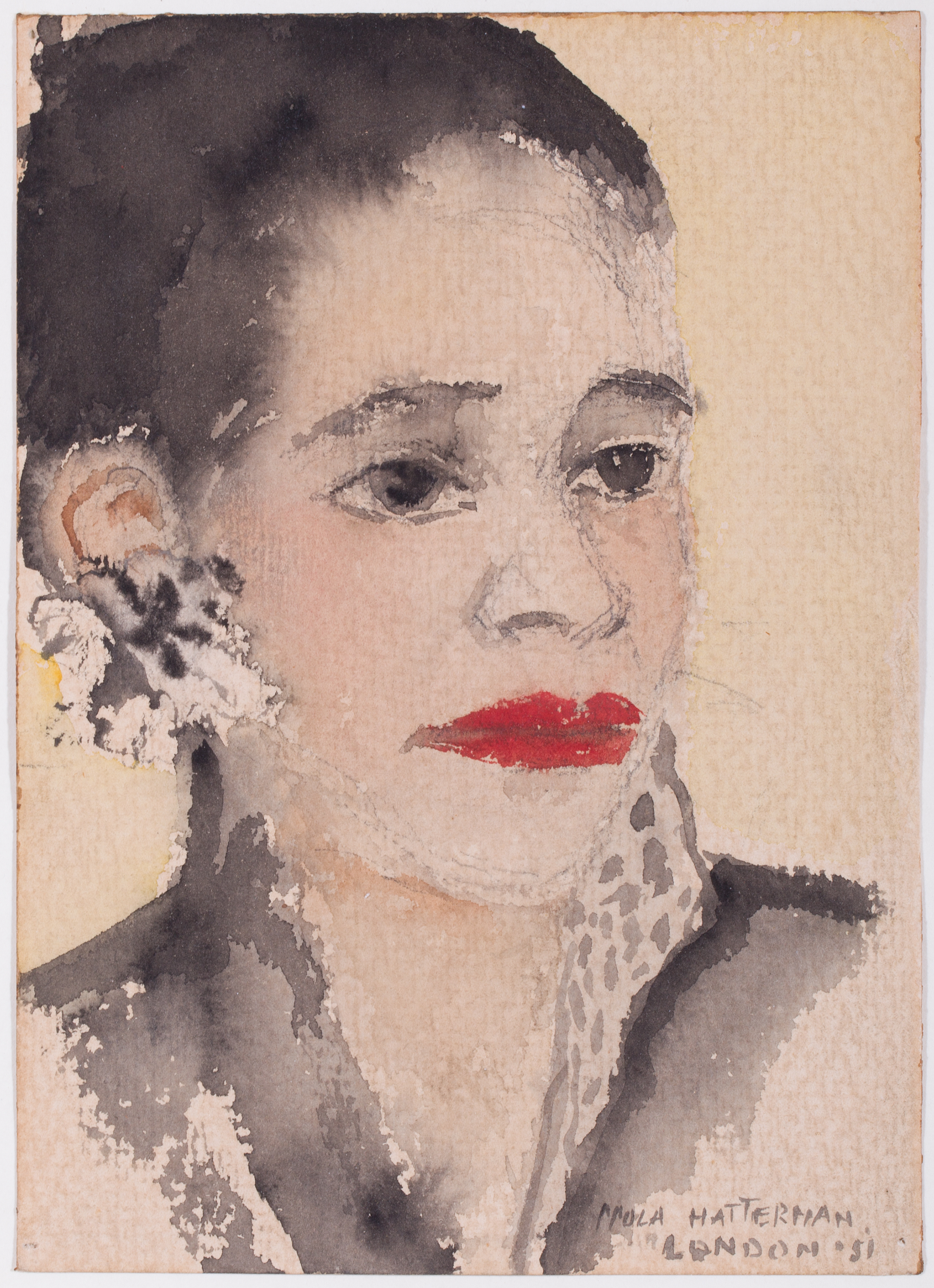

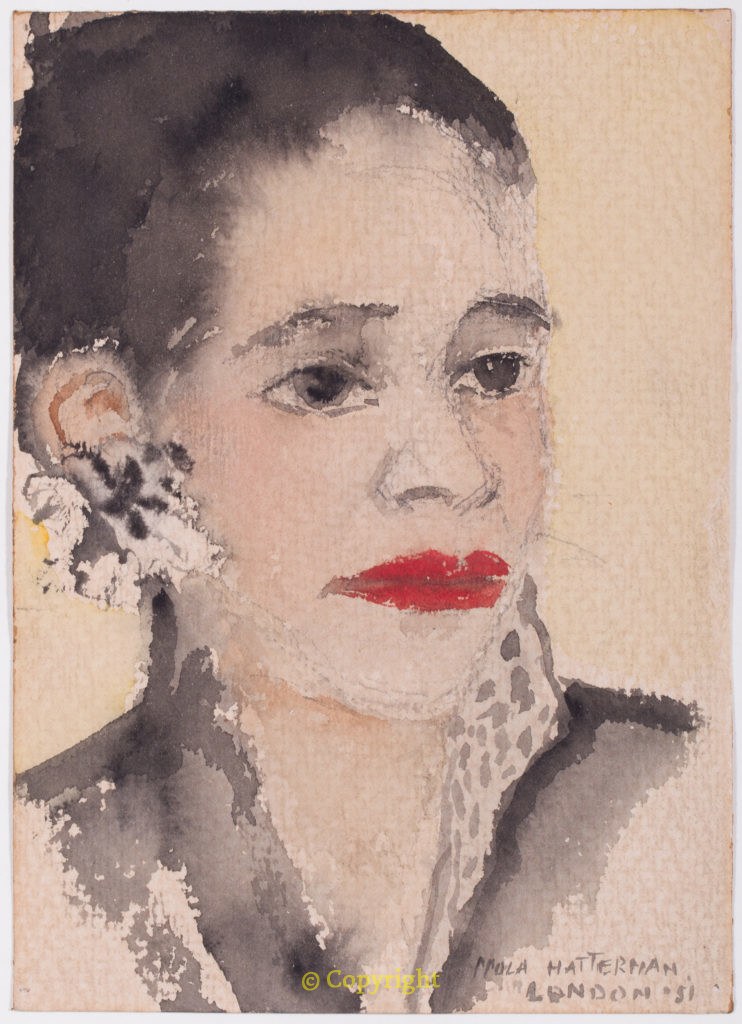

In the autumn of 1945 Nola took part in the group exhibition Art in Freedom in the Rijksmuseum, together with other artists who had refused to register wit the Kultuurkamer. May 1946 her work was shown in ‘Onze tentoonstelling (Our exhibition)’ at the Rokin in Amsterdam, together with that of communist-minded artists. She did not return to the artists’ associations of which she had been a member before the war. She insisted on her theme: the world of the – oppressed, but militant – black people and she often exhibited together with black and white female artists. For example, in 1948 she was invited by the Amsterdam art dealership Santee Landweer for a duo exhibition with the Ghanaian artist L. Ama Hesse who worked in London. Rosey Pool – ambassador of black Afro-American literature in the Netherlands – contributed poetry on that occasion. In 1948 Nola exhibited her work in Hilversum together with other Dutch painters including Queen Wilhelmina and in 1949 she participated in the group exhibition Women artists from the Netherlands in London. In Londen she exhibited her work in May 1950 together with the Jamaican dentist / sculptor Ronald Moody with the support of The League of Colored Peoples. Ronald was the brother of the founder of The League: Harold Moody.

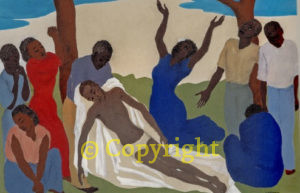

On that occasion her Zwarte Pieta, Black Pieta (1949) was on display. In the Daily Herald the ‘coloured Christ’ was described as ‘Europe’s most controversial picture’.

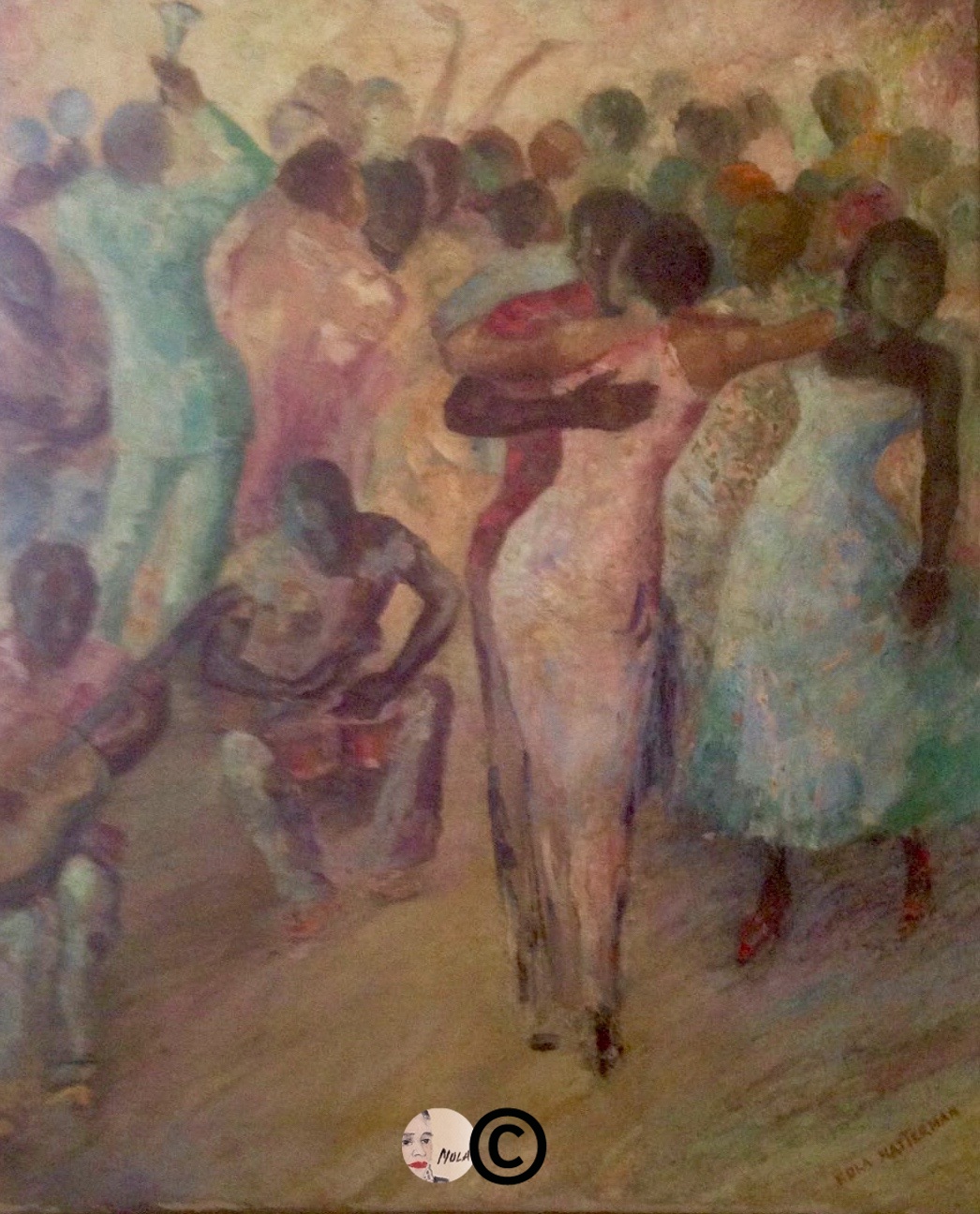

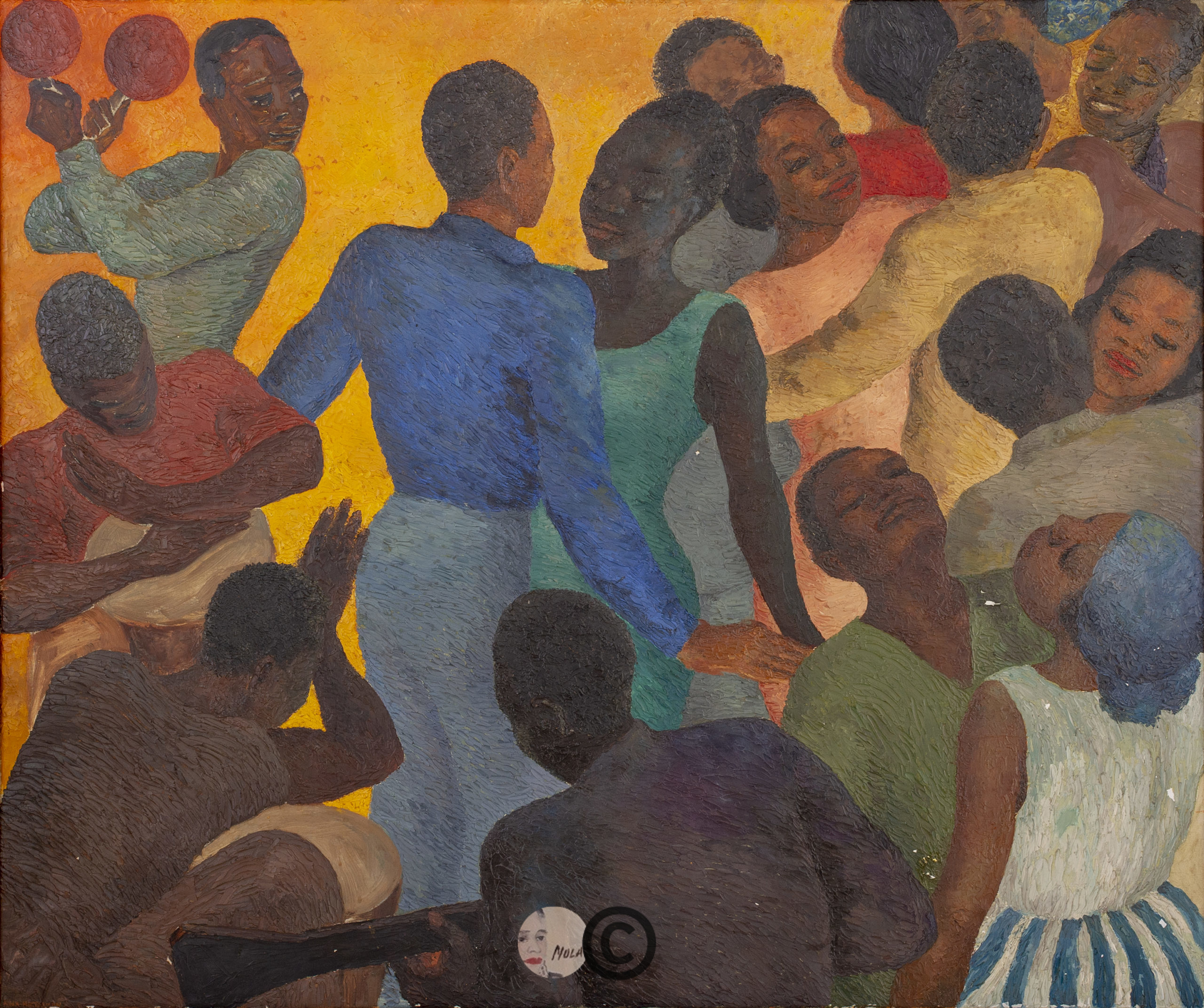

Reviews from the pre- and post-war years show that the work of Nola Hatterman was reviewed several times. Exemplary in this respect is the review of Pierre Janssen regarding the exhibition at the Catharina Gasthuis in Gouda and the Schielandshuis in Rotterdam: ‘The largest and most important part of her work … shows negroes (sic!) in portrait and in imagination, reverently observed or dreamed full of compassion and love. It could not be otherwise that this mixture of human beauty and propaganda had to lead to an unbalanced result. Sometimes Nola Hatterman makes beautiful, penetrating portraits (…), sometimes paintings with all the zest for life of the negroes (sic!) (West-Indisch Dansfeest, West Indian Dance party), sometimes drawings and lithographs with a perhaps somewhat sweet refinement, sometimes a drawing in which the shrewd content dominates everything (Vervolgden, Persecuted). But all these critical considerations do little for Nola Hatterman. Because of his praiseworthy tendency, her work is unique in the Netherlands and perhaps far beyond. After all the modern artists, who freely form and derive motives from the art of the negroes (sic!), Nola Hatterman is an artist who sought and understood the people behind the art of negro (sic!)… ‘ says Pierre Janssen in Het Vrije Volk on 8 April 1952.

In 1951, Nola’s work was shown at the Central Museum Utrecht in an exhibition showcasing the work of British and Dutch painters. For a complete list, please see Nola’s biography ( in Dutch!) or click on this link.

Abstract art – heretofore banished by the Nazis – was very popular. New, abstract art movements had discovered African culture as a painter’s exotic object. Nola had nothing to do with that, she portrayed black people as members of contemporary European society in a realistic style. But realism was out of date. As Nola’s pupil Brigitte Pos-Kray (wife of the Surinamese-Dutch Willy Pos) put it: ‘It was not avant-garde enough, it was a form of snobbery!’ For Nola reason to explore other possibilities.

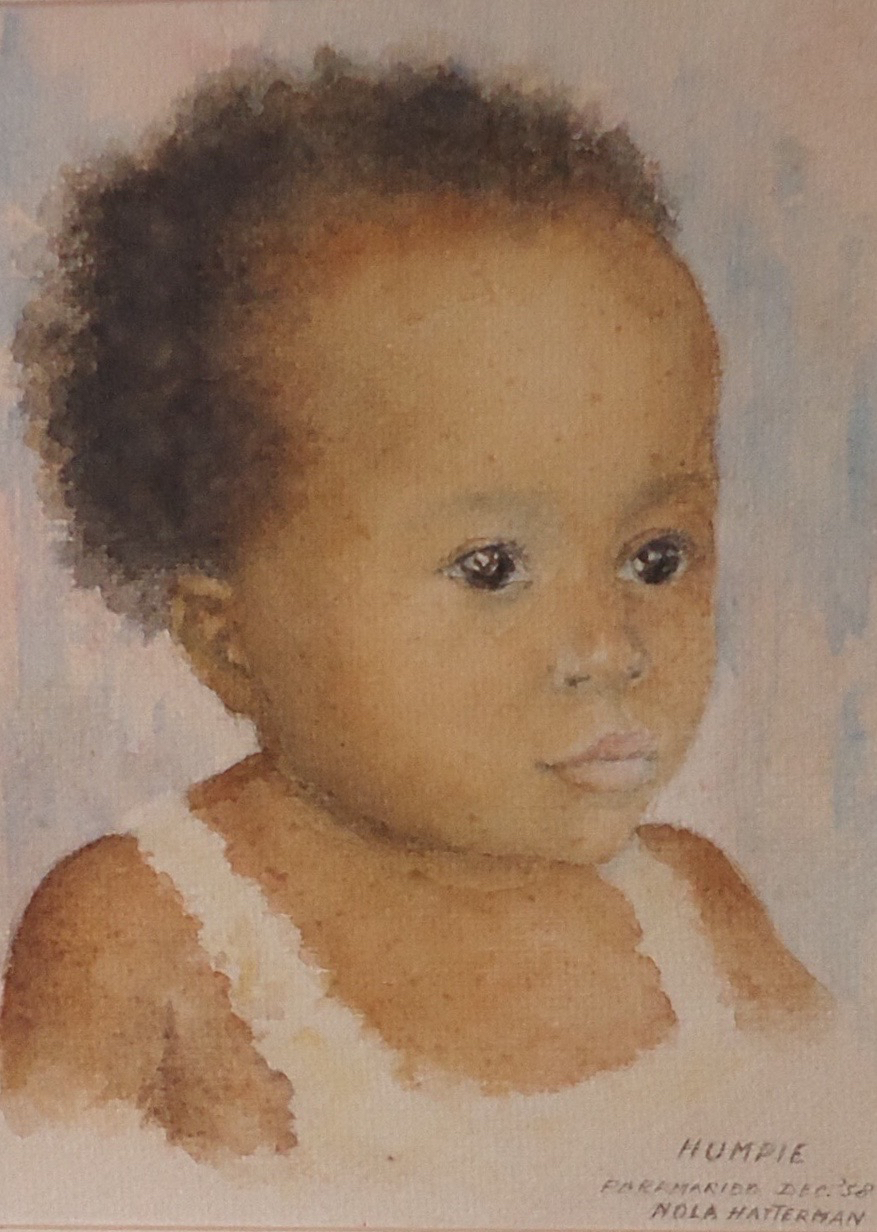

CCS

She wanted to go to Suriname to teach at the Cultural Center Suriname (CCS): the sister organization of the Foundation Cultural Exchange Suriname and Dutch Antilles (Sticusa) in The Hague. She asked for a broadcast, but drew a blank. Because of her communist sympathies – it was the time of the Cold War – she was not welcome in Suriname. Nola left for the Caribbean in 1953 by herself. The British Minister of Colonies had invited her to the Trinidad Art Society. She held an exhibition in Trinidad and then headed for Suriname, where she would stay forever. Her exhibition there was very well liked. The Surinamese writer Dobru wrote in his autobiographical work Wan monki fri that until her arrival the European beauty ideal was the norm in Suriname. ‘Nola’s first exhibition was a revelation to many. Finally the Negro (sic!) was beautiful.’ There were also favorable reviews in the newspapers. In the years that followed Nola would mainly focus on education.

Expo with students

In school, Nola organized various exhibitions, such as the ‘Talent Parade’ of December 1960, were work of the most advanced students was shown. Sometimes Nola showed her work together with pupils and other Surinamese artists. Occasionally also in the Netherlands: in 1967 she participated in the exhibition entitled Contemporary Art from Surinam that visited several places in the Netherlands. In 1980, four years before her death, she participated in the group exhibition of Surinamese artists in Paramaribo, entitled Kunstcollectie 1980. At the time, Nola was applauded by her Surinamese generation, the younger generation found her work ‘outdated’. Nola withdrew somewhat disappointed in the interior of Suriname: Brokopondo-Center. There, together with former pupil Stuart Manuel, she provided lessons for the children of Brokopondo and completed the fourth-panel on slavery: Attack on the plantation. To her great joy, in 1984 she was approached by the Surinamese artist Paul Woei to take part in the group exhibition of Surinamese artists – including a few of her students. This made her very happy. The exhibition was called: Identity. Unfortunately, she would not experience the opening. On the way to Paramaribo to make the final preparations for the exhibition, she died in a car accident. At the end of her life, Nola wanted an exhibition at the Tropenmuseum, but even more so at the Stedelijk Museum where she once started. Unfortunaly this would not happen.

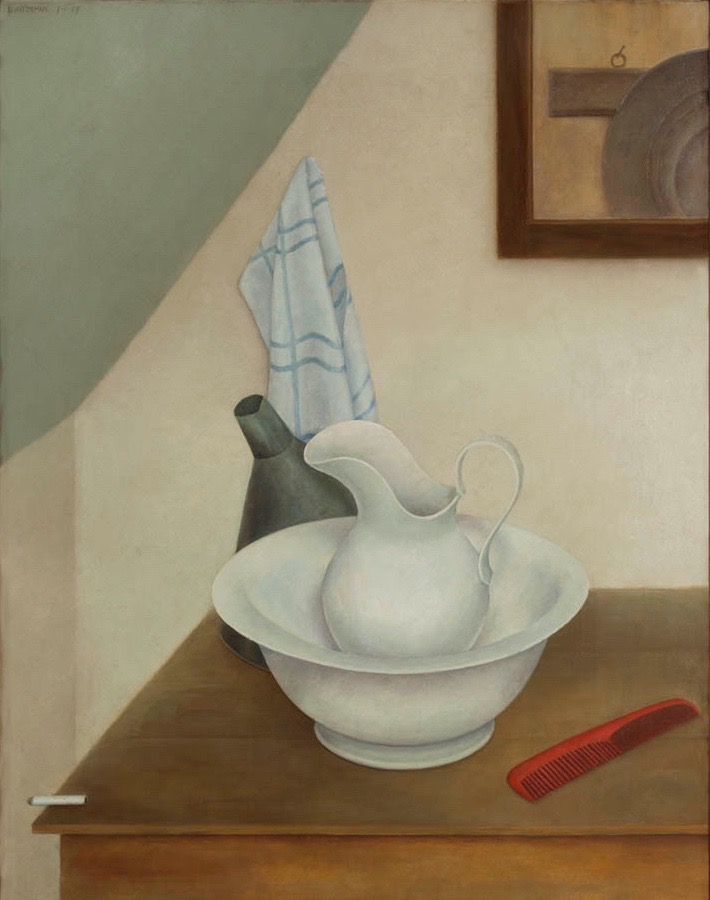

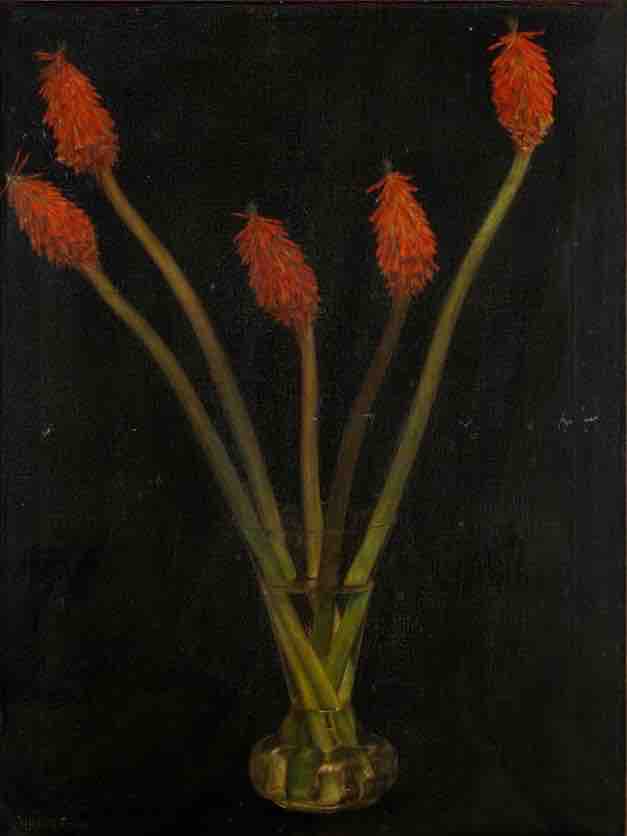

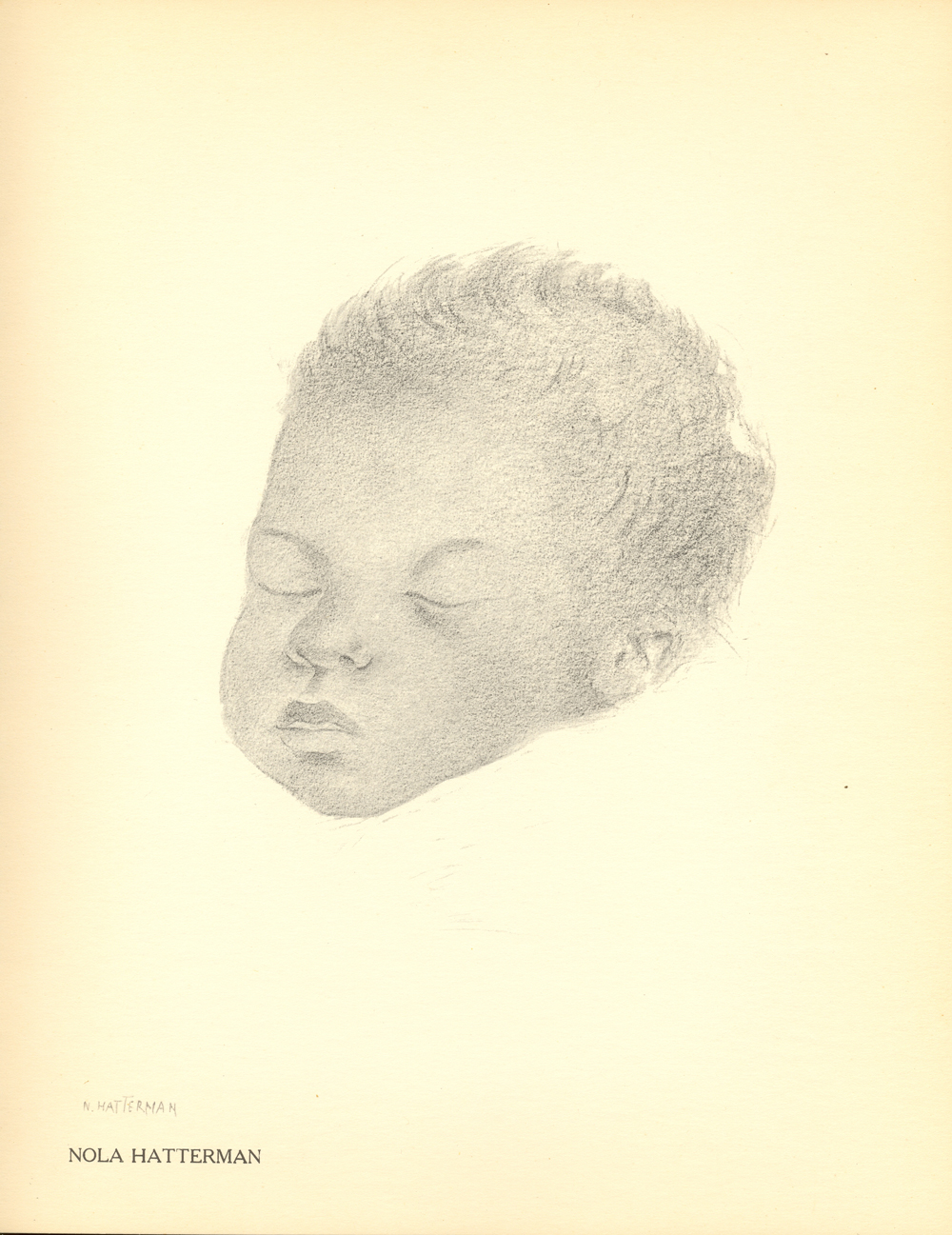

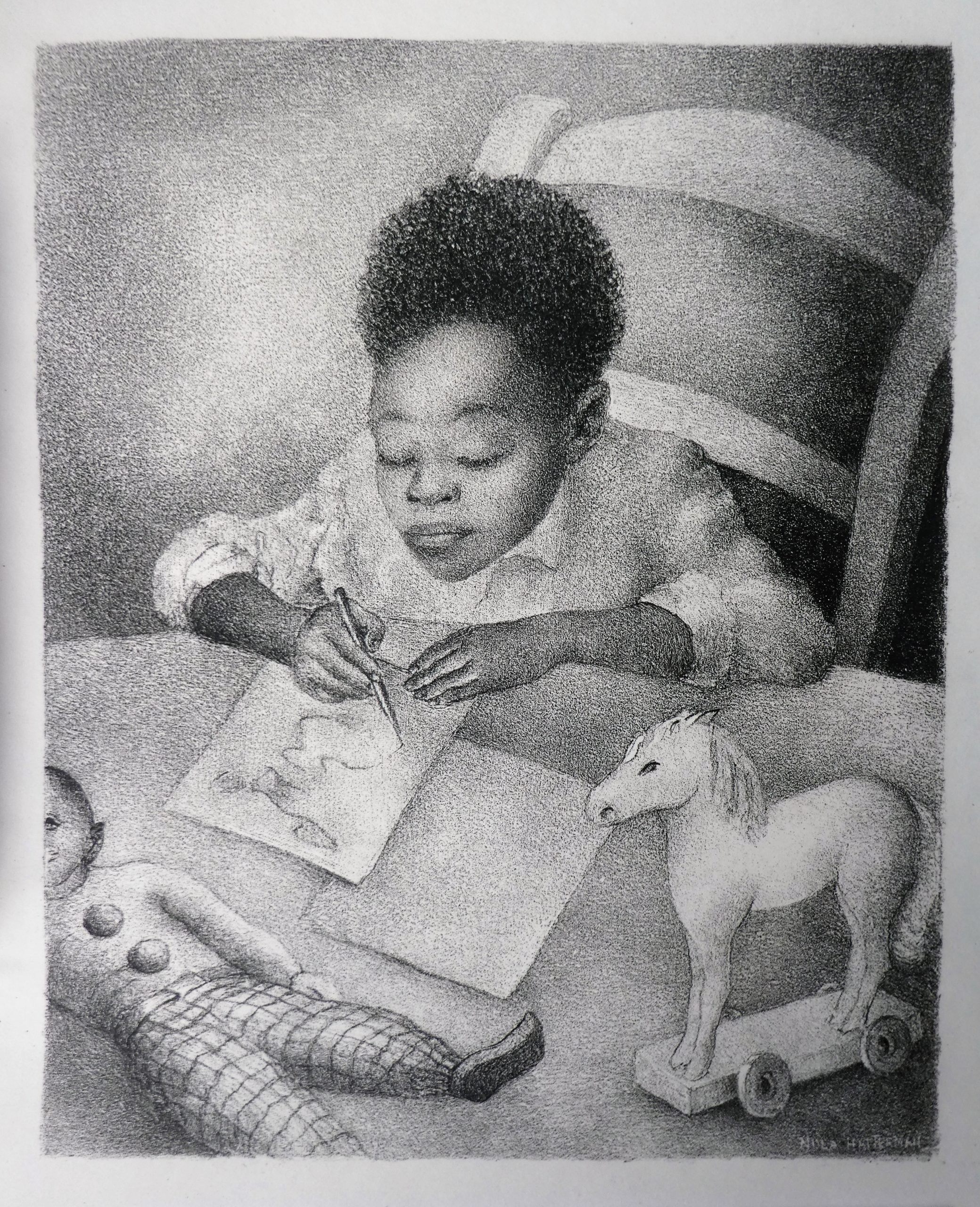

Portrait painter overseas migrants

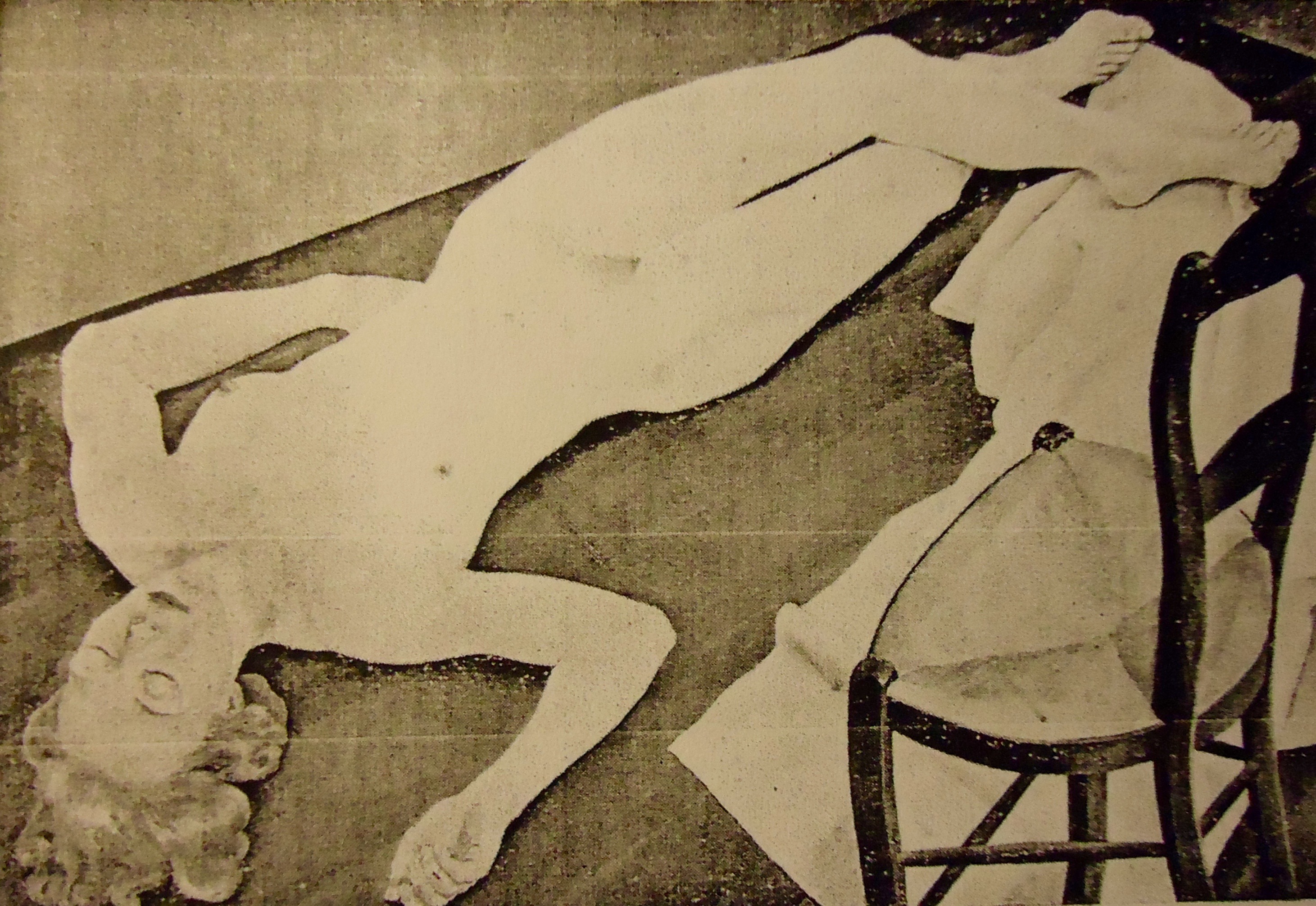

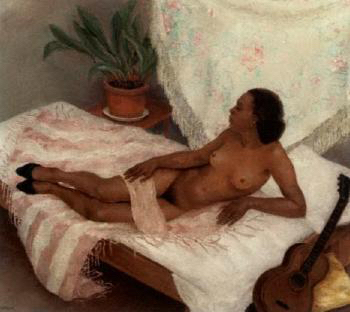

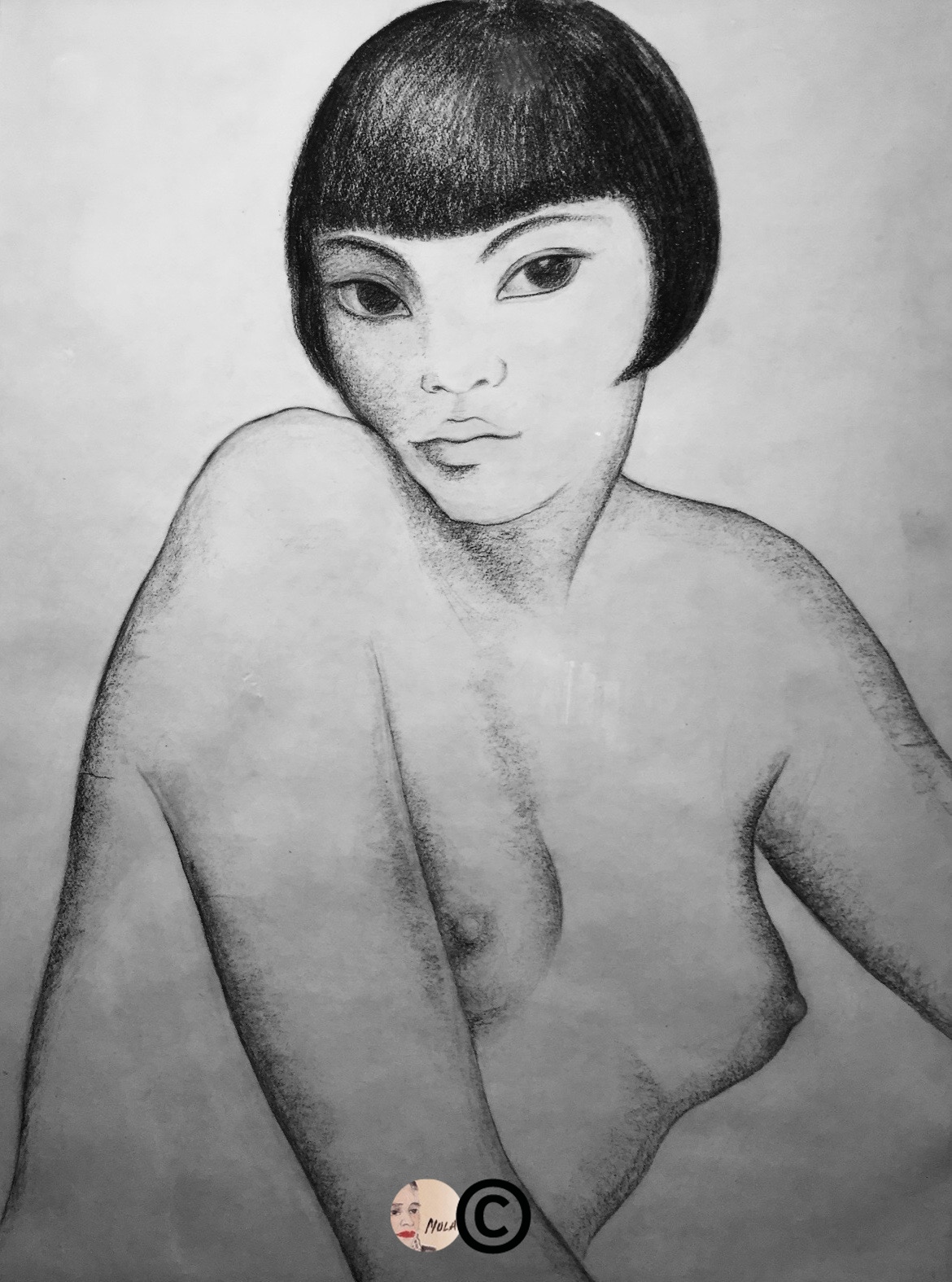

Later she suggested she only portrayed overseas migrants from the (former) colonies: Dutch Indians, but especially Afro-Surinamese. Exhibition catalogs show that her oeuvre was more comprehensive and also contained still lifes, landscapes, nudes and portraits of white people.

Important themes in her work

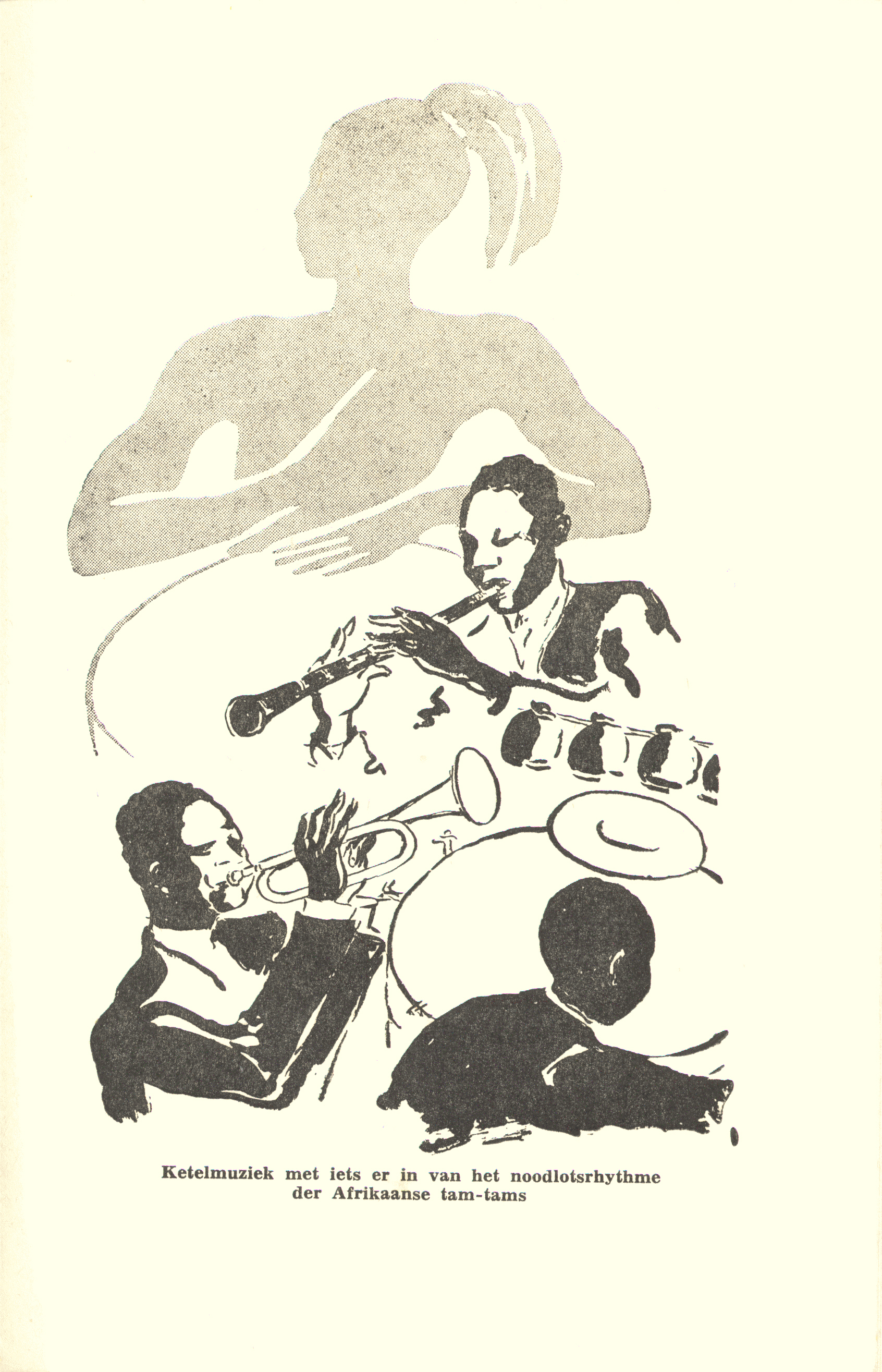

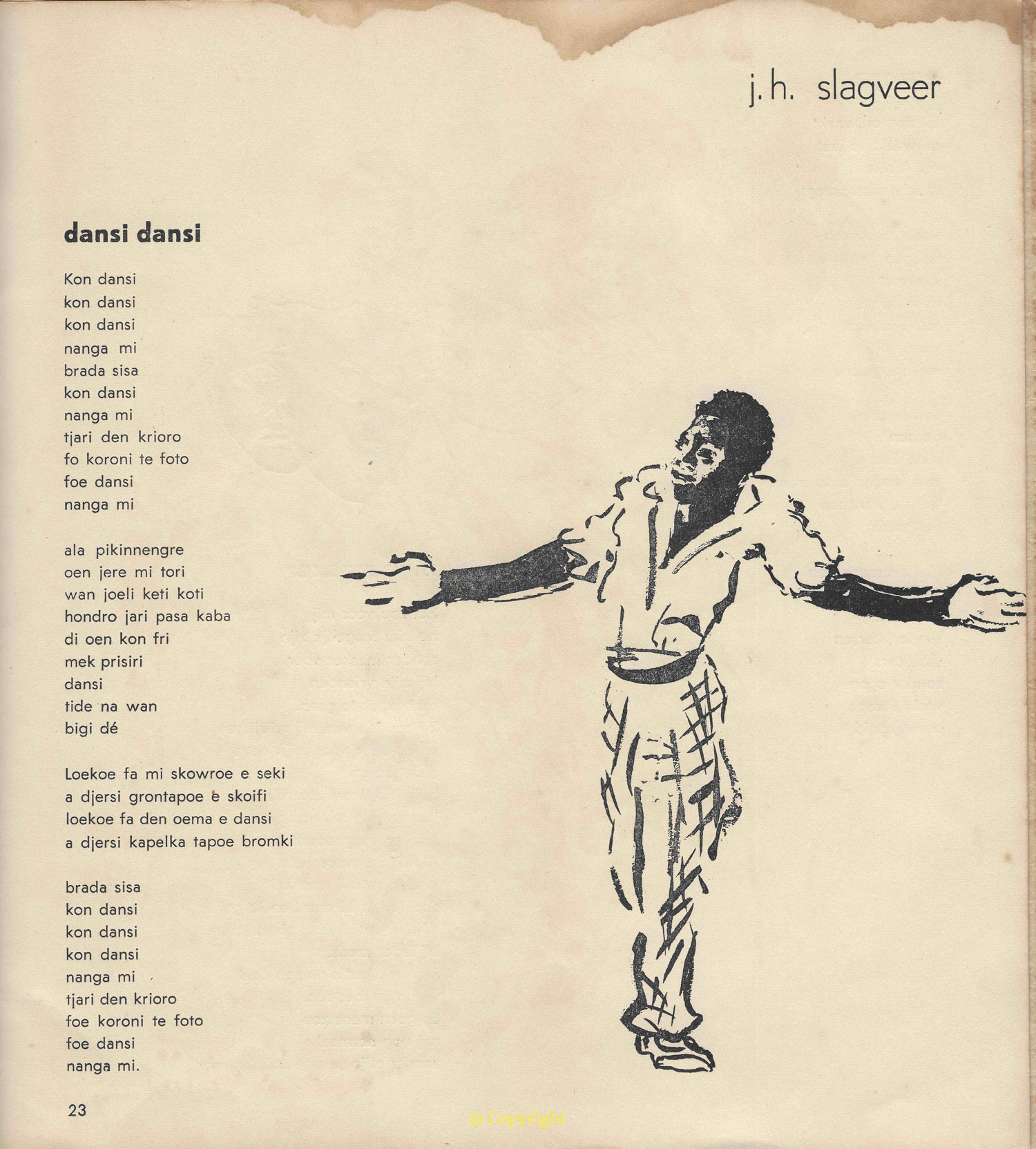

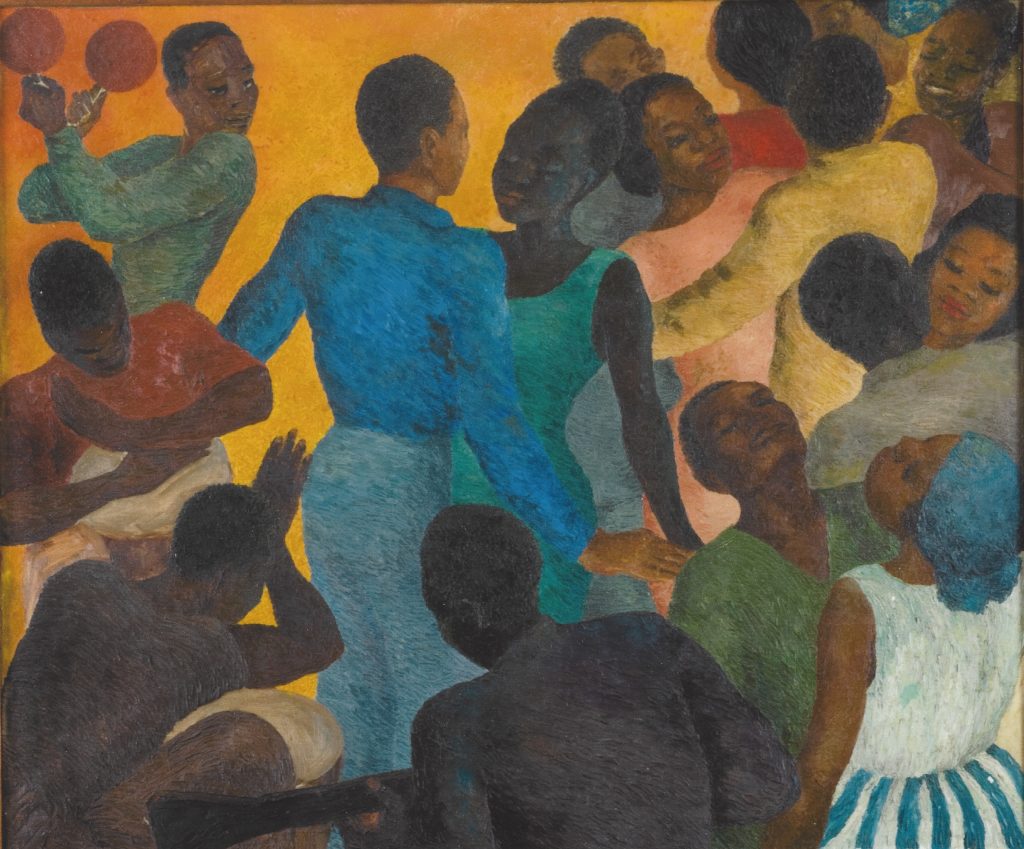

After the turbulent 1920s, a period of economic depression was followed by the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. Despite the crisis, the entertainment industry flourished as never before. Black jazz and dance music were – banned and degenerated by the Germans – extremely popular with Nola and her (Surinamese) friends. Jazz (dance) stood for a new way of life: rebellion against the established order. Jazz and dance form a prominent theme in the work of Nola, such as the titles Jazz (1934), the Trumpeter (1936), Blues singer (1939), Surinamese dance party (1940), West Indian Dance party (ca. 1951), Thoughts in blue – (to a non-danced blues by Percy) (1950s), Portrait of a saxophonist, That one dance and Jazz, Jazz (1976) show.

Music and dance are traditionally popular themes in the imagination of black people and date from the time of slavery, thus suggesting a happy slave life. European artists who recorded these scenes probably ignored the meaning of dance and song as a form of resistance against the colonizer as well. The question is how we should interpret these themes in the work of Nola Hatterman. How did her work relate to the cliché of the cheerful, swinging and singing black man and woman?

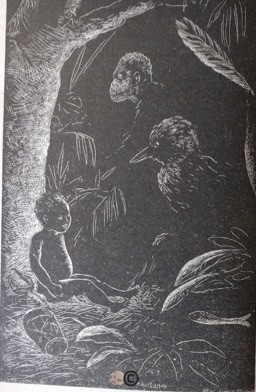

A striking theme are her four-panel on slavery, inspired by Anton de Koms Wij slaven van Suriname, We slaves of Suriname, and the resistance against slavery: marronage. At the time, a barely touched subject in Surinamese and Dutch art history.

England

After the war Nola Hatterman gave lectures together with Rosey Pool: ambassador of black literature in the Netherlands. Rosey Pool recited poetry, while Nola explained the exhibited works and gave lectures about the life and subordination of the black ‘race’. In return Nola provided illustrations for the books Rosey wrote. To a lot of artists in the Netherlands, Paris was a source of inspiration. Nola would certainly have gone to Paris. At the end of the thirties she went there to attend a (number of) international political conference(s). Without any doubt she will have visited artist friends and museums but much remains obscure. It would seem that England was important for the rest of her career as a painter, that is to say: London.

This may have been because her friend Rosey Pool lived there since 1948, and Nola visited her. In 1948 she became a member of the Artist’s International Association in London. Please see the letter she wrote to Diana Uhlman about her membership. Uhlman was the wife of artist/writer Fred Uhlman): they were collectors of West-African sculptures. In 1949 she took part in the exhibition Women artists from the Netherlands in London. In the same year, Bronzes of West-Africa by Leon Underwood appeared, about the technique of making bronze sculptures in the old African kingdoms of Benin and Ife in Nigeria. This book as well as the collections of African and Egyptian art in the British Museum inspired her to distinguish between the ‘European’ and the ‘non-European’ type which she taught at her school in Suriname. Please see under ‘Education’. (These days there are discussions about the return of collections stolen during the colonial era from ancient Nigeria.) The invitation Nola received to come to the Caribbean, which eventually took her to Suriname, came through London.

Style

On the basis of her most famous works: Stilleven met Borstplaat, Still Life with Fondant, and Op het terras, On the terrace, and other work she made around the 30s, she is counted as a representative of the New Objectivity: a translation of the German-born art movement Neue Sachlichtkeit. It was characterized by objective realism and a search for the core of things. This was expressed in uniform color boxes without shadow and perspective distortion. Yet other movements are also visible in her works – impressionism, cubism, expressionism, art deco – and the influence of painters such as Matisse. An adequate description of her work is still lacking. A number of Nola’s works seem to have been lost – works occasionally crop up – or have not been described. This project aims to map and analyze the oeuvre in the form of a monograph of her work with essays by various (art) historians.

Female artist

Nola had strong feminist views. She offered resistance when it came to the subordination of women and in this oppressed position she felt kinship with other oppressed groups: labourers, the Jews, new arrivals in The Netherlands and colonised peoples. In Surinam she was a member of the women’s network the Soroptimists. She dropped a bombshell when she presented the woman in the book Vrouwen Kent Uw Rechten (1972) as a chained martyr. She wrote the book together with a former ambassador of Surinam in The Netherlands Irma Loemban Tobing-Klein. See under Illustrations on this page.

The question that arises is why Nola has no place in the Dutch art canon. Is that because of the varying quality of her work? Her limited oeuvre? Her choice of subject? Her commitment? Was that because she left for Suriname? Or did it have to do with the position of female artists at the time? Women were less prominent in the art world and certainly not as art critic. Ro van Oven, who interviewed Nola extensively in 1931, belonged to that small army of female critics who might try to bring the art of women to the attention of the public.

Controversies

In the first half of the 20th century, Nola was both admired and vilified for her portraits of black people in the Netherlands. After World War II, she was done, since realistic work was considered outdated. In Surinamese circles she was both loved and reviled. She was very popular with the first generation of Surinamese she knew from Amsterdam and with whom she shared their ideals for an independent Suriname and their struggle against racism in the western World. The younger generation of Surinamese – raised with the ideals of the 60s and the Black Power movement – had both a different view on art and the position of ‘foreign’ Dutch in the face of an independent Suriname (1975). At that time it led to friction. Afterwards her merits as pedagogue were appreciated. It is no coincidence that one of the art academies has borne her name since 1984. But what is anno 2020 the opinion about the artistic work of Nola Hatterman and the work she made in Suriname? What is her place in the Surinamese art canon? And how is her oeuvre valued in the light of contemporary discussions about white privileges and cultural appropriation? Lately, in the postcolonial debate raging in the west (Netherlands), the position of Nola as a white painter of black models and teacher in a colonial setting is (once again) under discussion. Her position is different in Suriname, in 2020 there was an expo to introduce the public to her (unknown) artworks. Nowadays in Suriname she is seen as a Surinamese artist.

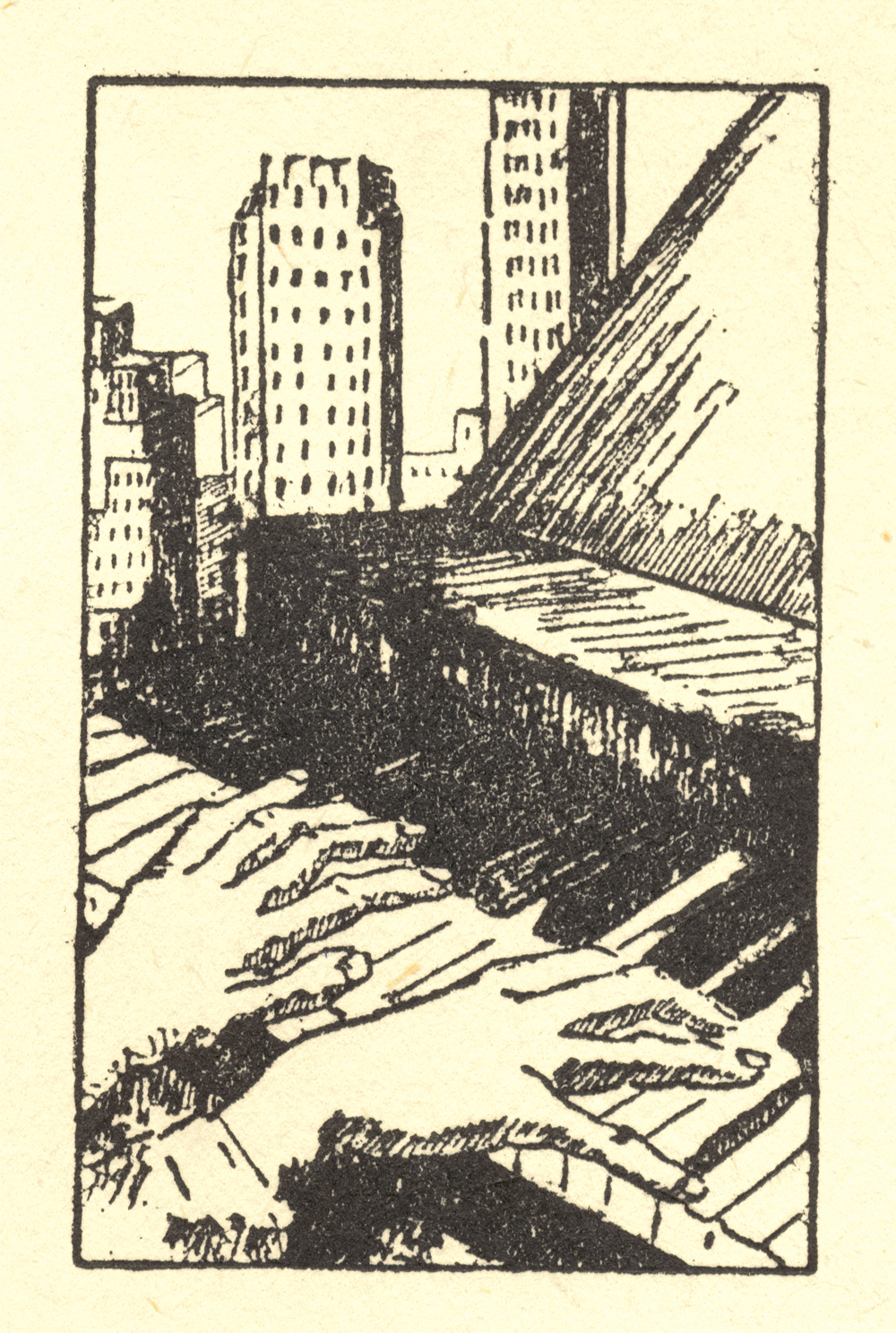

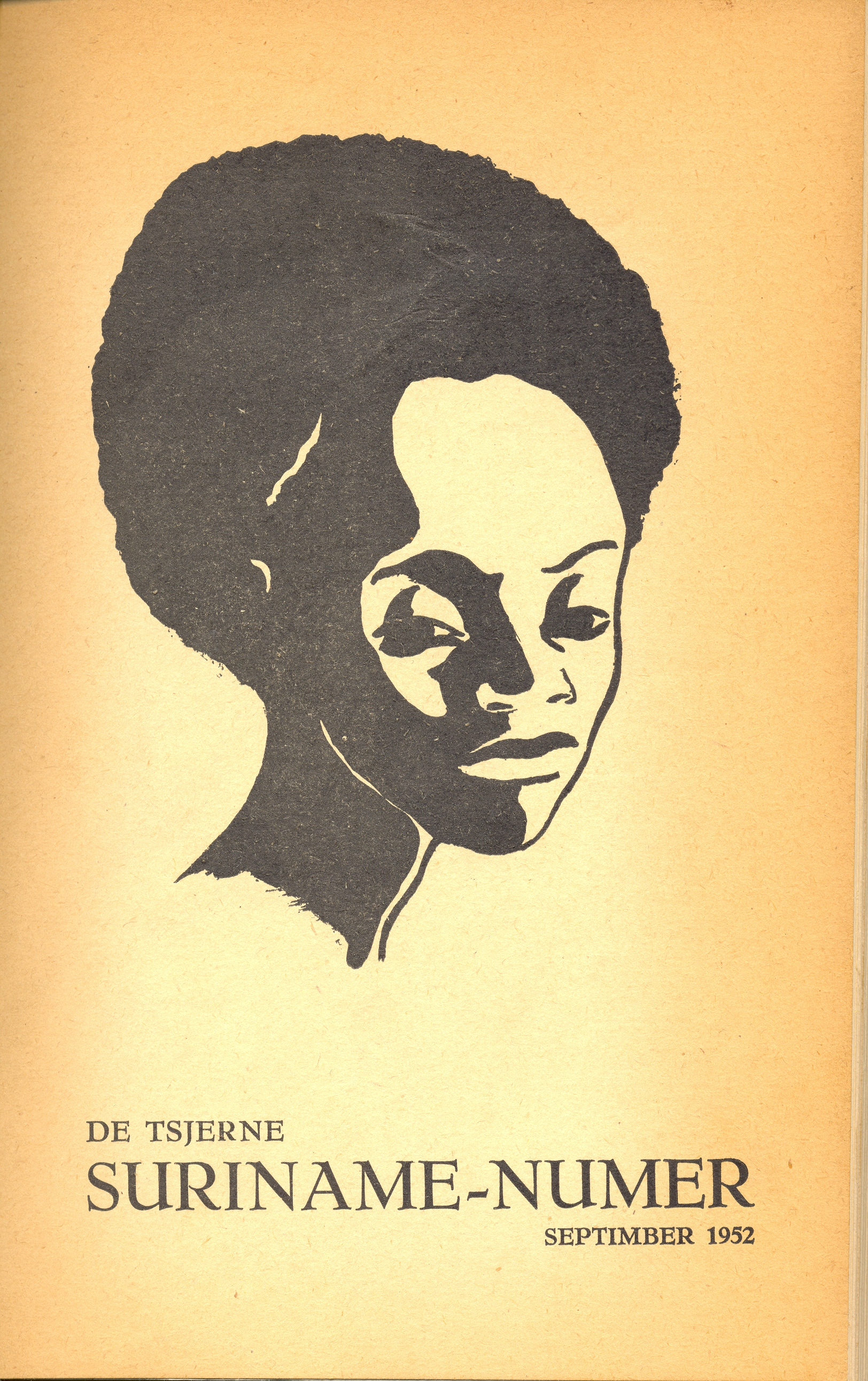

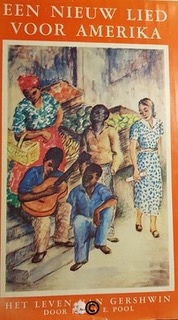

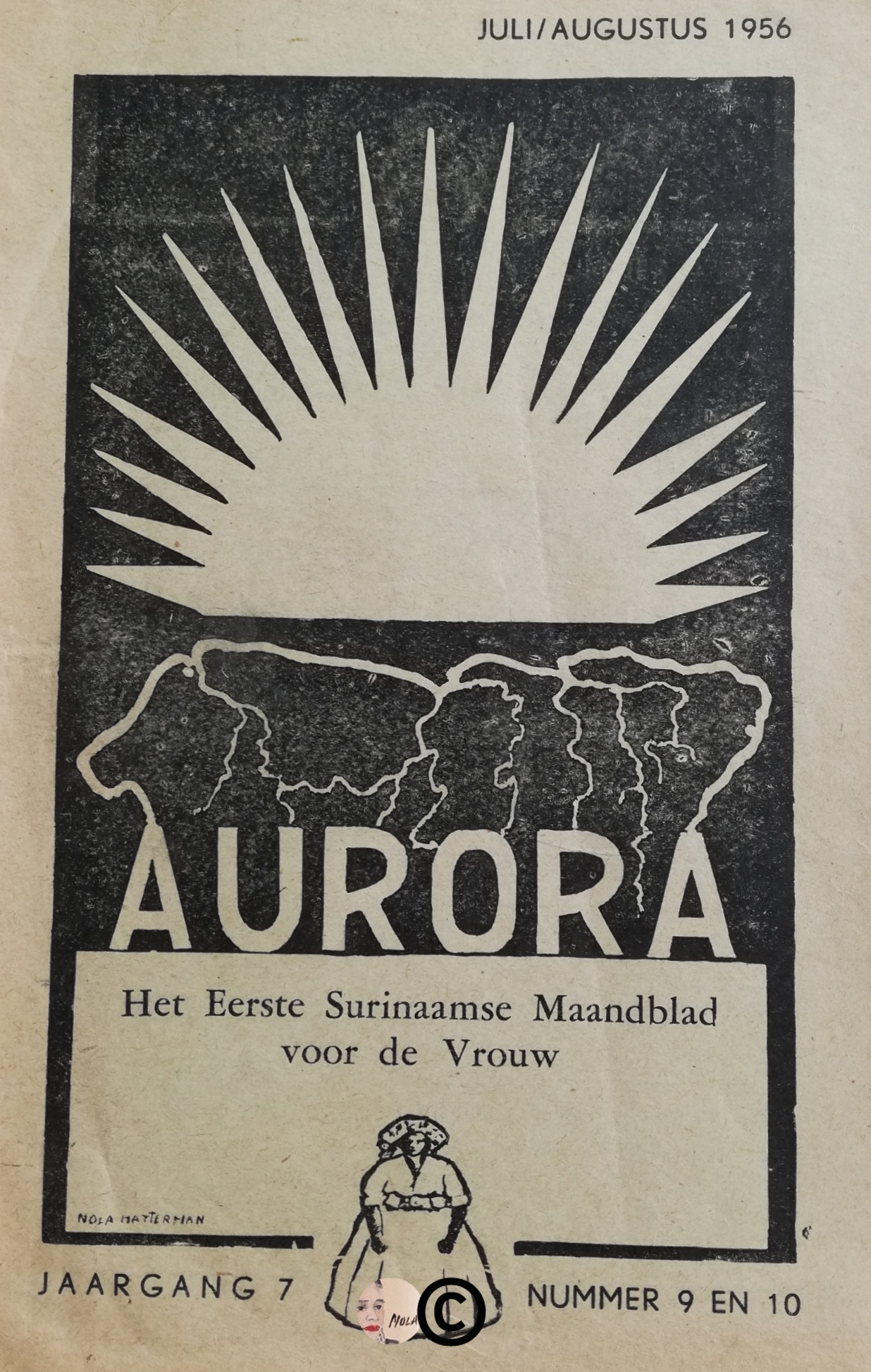

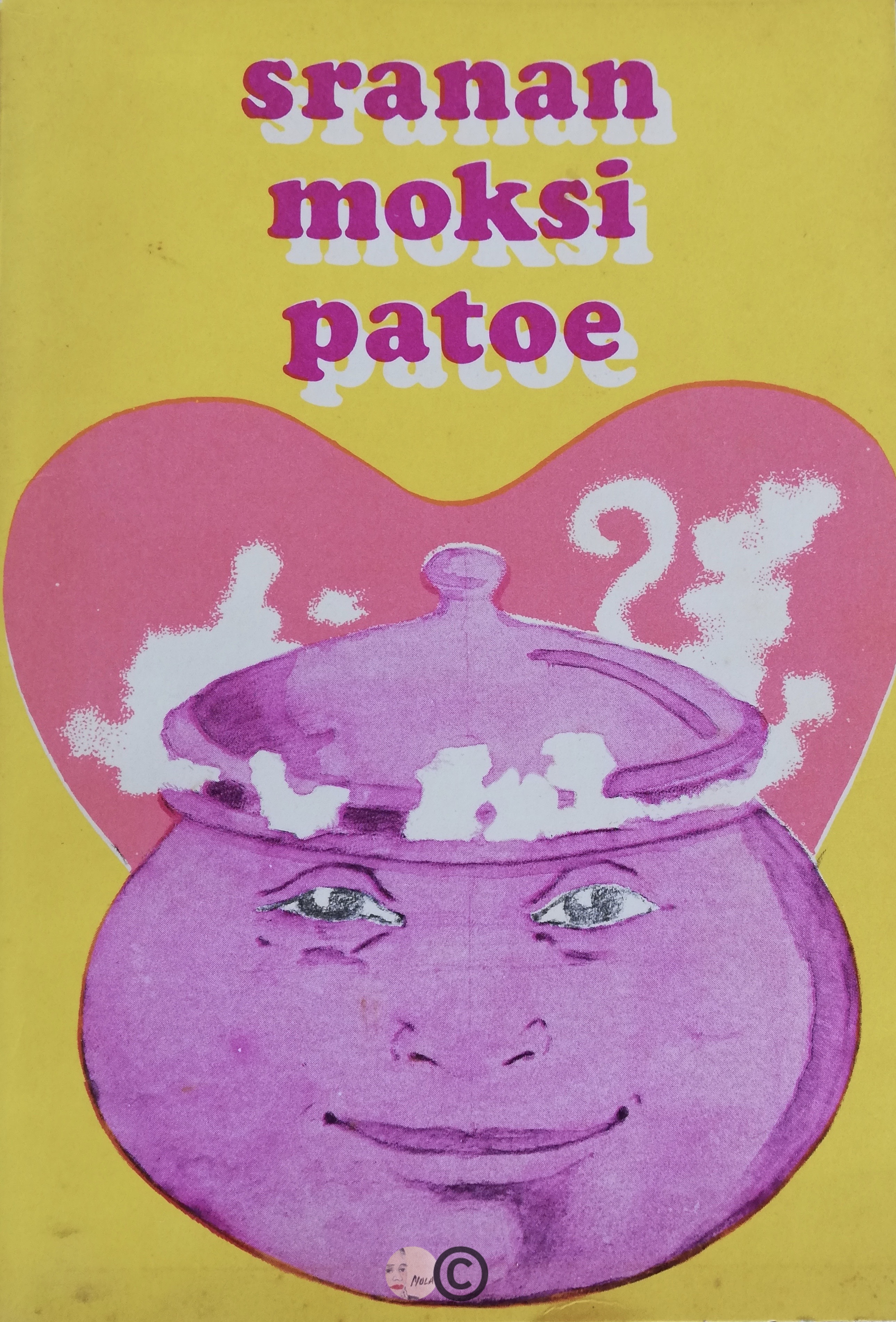

Illustrations

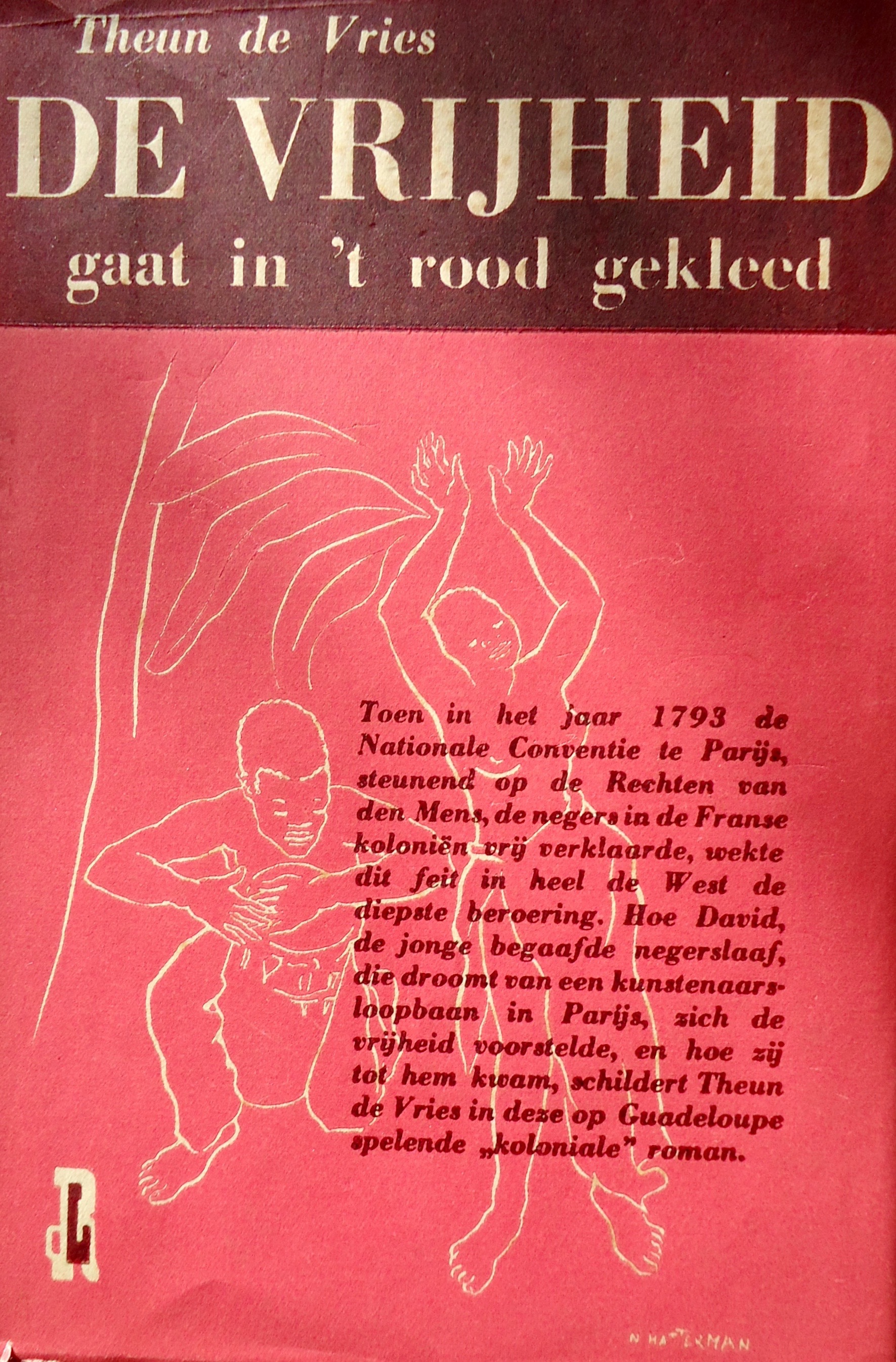

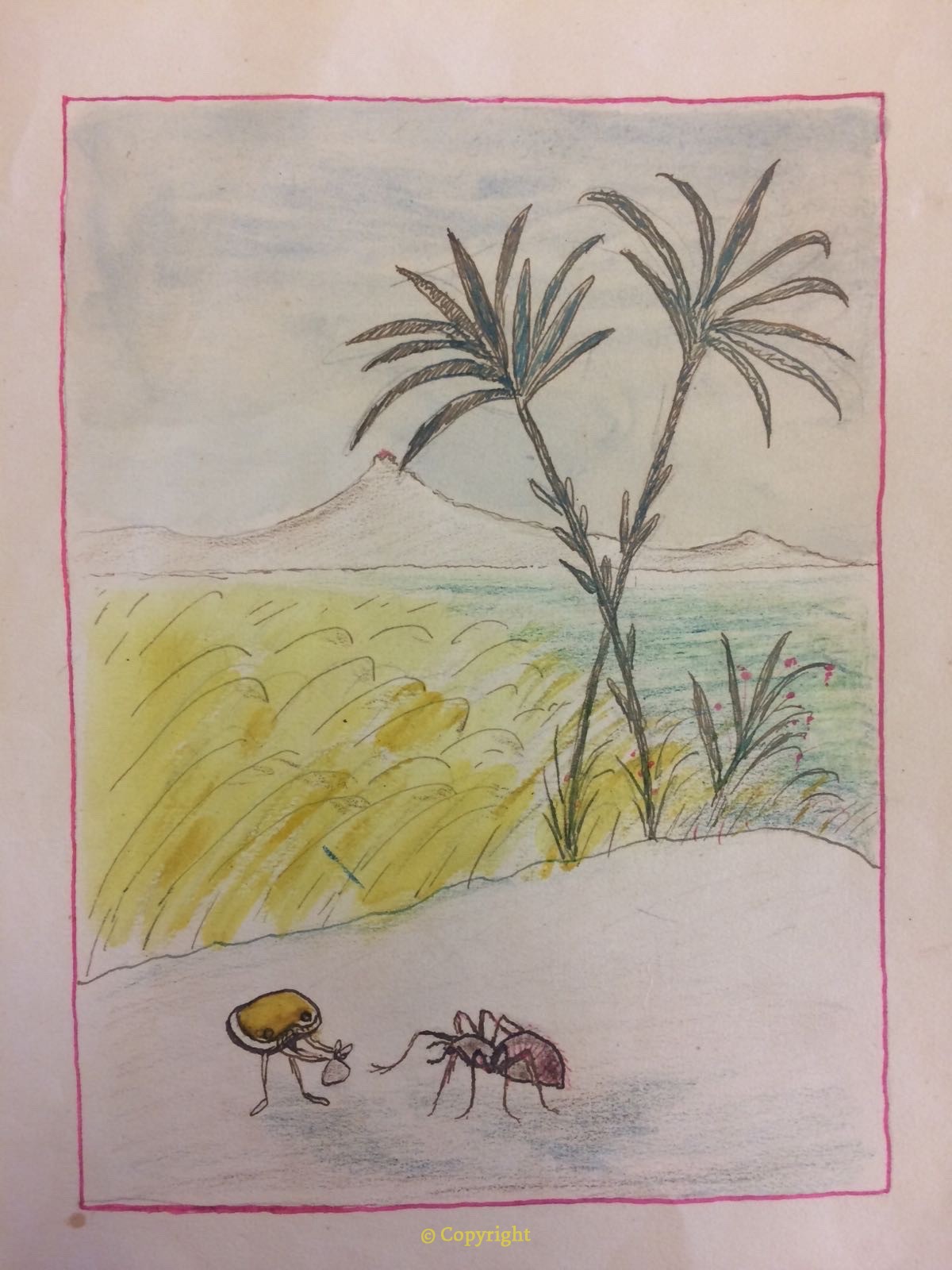

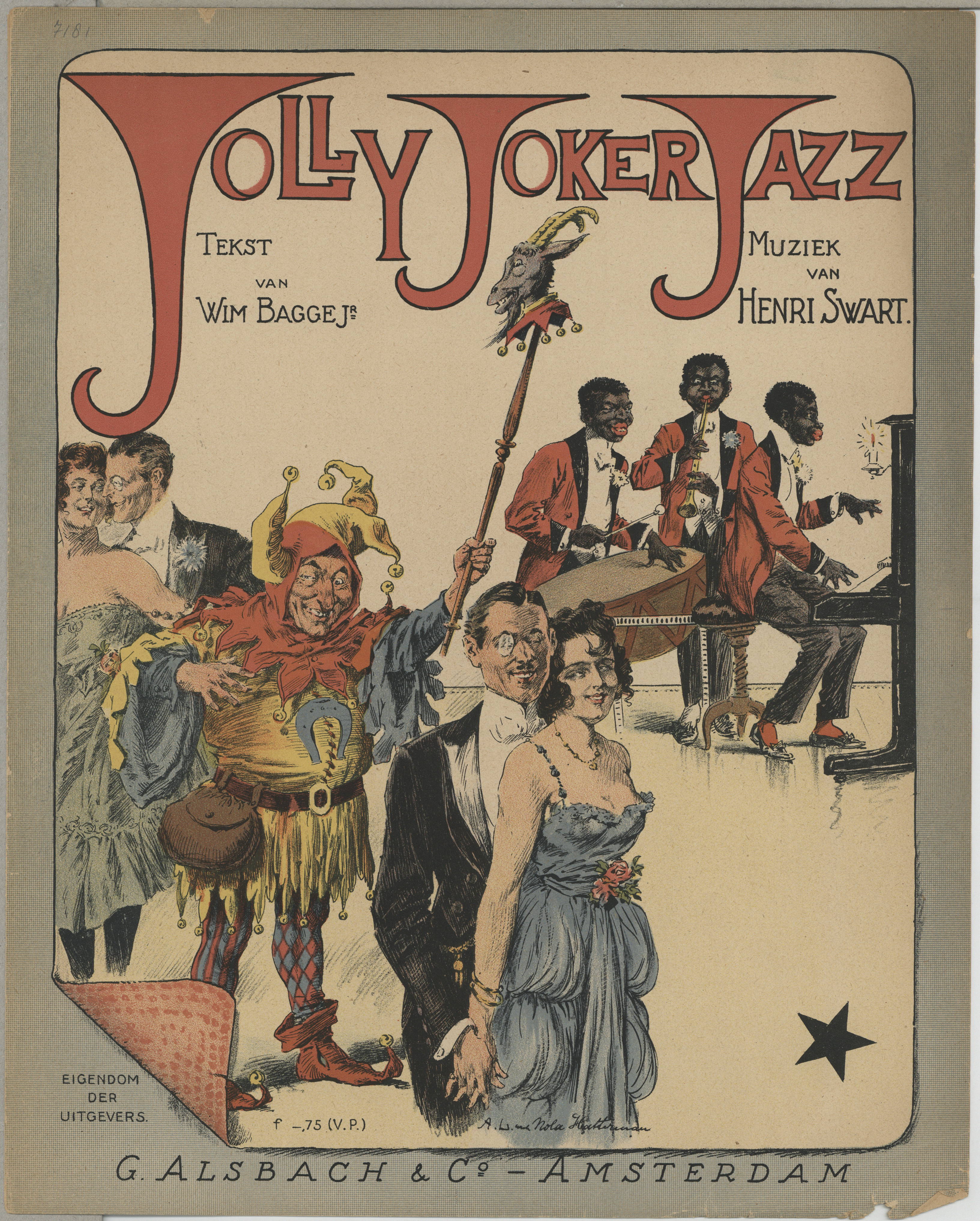

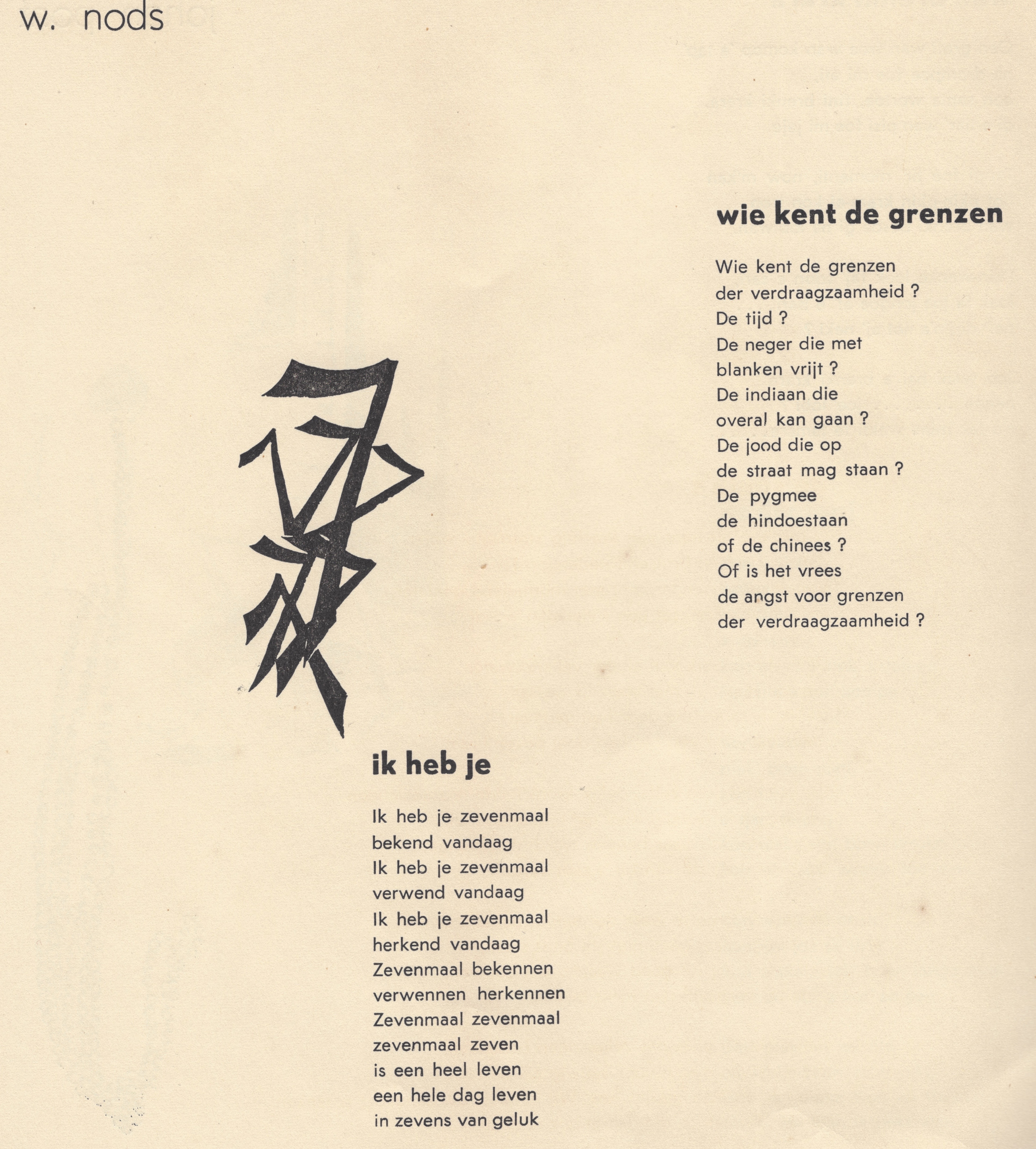

In addition to being an artist, Nola was also an illustrator of books and book covers. She produced the first findable book covers for her communist-minded husband: the writer Maurits de Vries. She presumably drew the albumillustration of Jolly Joker Jazz composed by Henri Swart, text by Wim Bagge Jr. Probably in the 1920s, when she was still an actress. It appears that she mainly produced illustrations for friendly artists / activists from communist, anti-fascist and anti-colonial circles. For Surinamese communist and activist Otto Huiswoud: editor-in-chief of the illegal international trade union magazine for black workers The Negroworker (sic!), for the magazine Surinamers in Nederland (Surinamese in the Netherlands) of the Association of Surinamese Workers in the Netherlands (see slideshow), for the anti-colonial novel by the Dutch communist Theun de Vries, for the Surinamese freedom fighter Anton de Kom and the ambassador of black literature in the Netherlands: the Dutch-Jewish Rosey Pool. She also took care of the cover of the Suriname-number of the Frisian magazine de Tsjerne, whose editors recognized themselves in the Surinamese struggle for recognition of their own native language. In Suriname she made drawings for the literary magazine Soela, in which Surinamese poets published in both Dutch and Surinamese. Not only Suriname, also The Dutch East Indies were in her sight. For the book translated in Bahasa, intended to introduce in 1949 Suriname to Indonesia in the context of the Dutch-Indonesian Union: Suriname Jang tak terkenal, she collaborated with the Surinamese-Dutch writer Albert Helman (Lou Lichtveld). It seems this book was not printed until 1954 (in beautiful colour print). In his article in the magazine El Dorado (1st jrg, no 12, December 1949), the author, WL Salm, describes how the manuscript was already finished in October 1949, but the official in Batavia, Hilkemeyer, found the content ‘unacceptable’. It is not clear exactly what happened afterwards. Earlier Nola Hatterman designed the book cover of the nationalist novel of the Dutch-Indies born Soewarsih Djojopoespito Buiten het gareel (1946, 2 ed.). It is unclear whether she knew the Polish writer Maria Kuncewiczowa (1895-1989) personally, but in 1939 Nola made the cover of her book Cudzoziemka (1936). This book was translated into several languages. This psychological novel about the innermost feelings of a Polish woman in the interbellum appeared in Dutch under the title of Scherven (1939). She was very sympathetic to the woman’s cause. In Suriname Nola designed the cover of Aurora: the first Surinamese magazine for women. She was an active member of the Soroptimists in Suriname. In 1972 she published “Vrouwen kent Uw rechten” (Women know your rights), together with Irma Loemban Tobing-Klein. The illustration of a chained woman on a bed of nails with the caption “… the woman on her pedestal…” gave rise to a lot of commotion.

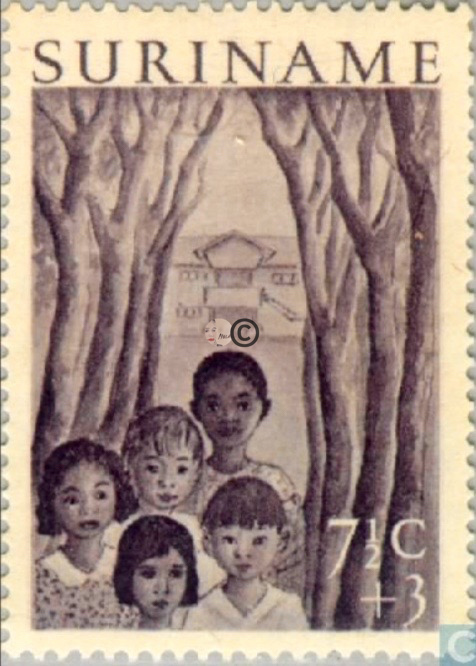

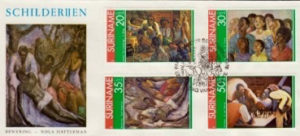

Work by Nola Hatterman was also printed on stamps in 1954 (children’s stamps) and in 1976 (The lamentation – Ode to a fallen slave from 1968). She also made pieces of scenery, wall paintings and decorated floats.

If anyone is acquainted with any other illustrations of Nola’s, please report it via the Forum or Contact.

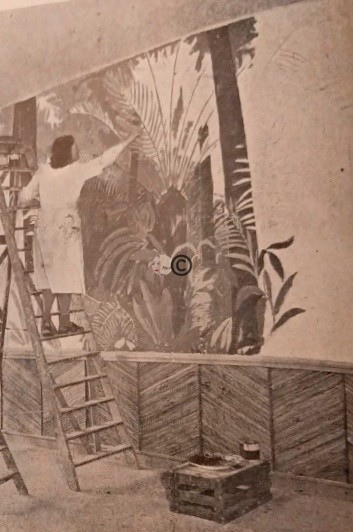

Decorations

Nola also made decorations. After the Second World War the liberation was celebrated with enthusiasm. There were parties everywhere, also in Amsterdam. Nola and her Surinamese friends participated in the pageants. Nola painted the decor of float nr 19. When the Surinamese Jimmy van der Lak opened his restaurant in Amsterdam in 1947, it was Nola who decorated the wall with a tropical design. She also designed and made the stage set of Eddy Bruma’s play The birth of Boni. Work by Nola  Hatterman was also printed on stamps in 1954 (children’s stamps) and in 1976 (The lamentation – Ode to a fallen slave from 1968). She also made pieces of scenery, wall paintings and decorated floats. For the independence fashion show in 1975 (Paramaribo) she created an outfit that symbolised the new-found freedom: a combination of a futuristic space travel costume and the traditional Surinamese ‘koto’

Hatterman was also printed on stamps in 1954 (children’s stamps) and in 1976 (The lamentation – Ode to a fallen slave from 1968). She also made pieces of scenery, wall paintings and decorated floats. For the independence fashion show in 1975 (Paramaribo) she created an outfit that symbolised the new-found freedom: a combination of a futuristic space travel costume and the traditional Surinamese ‘koto’

Lost work

Much of Nola Hatterman’s work has been lost or has not been inventoried. Occasionally supposed lost works pop up, such as Op het terras, On the terrace, Meisje, Girl, Trompettist, Trumpet player, Jazz, Danseres, Dancer, and Black Pieta. Sometimes the location is not clear.

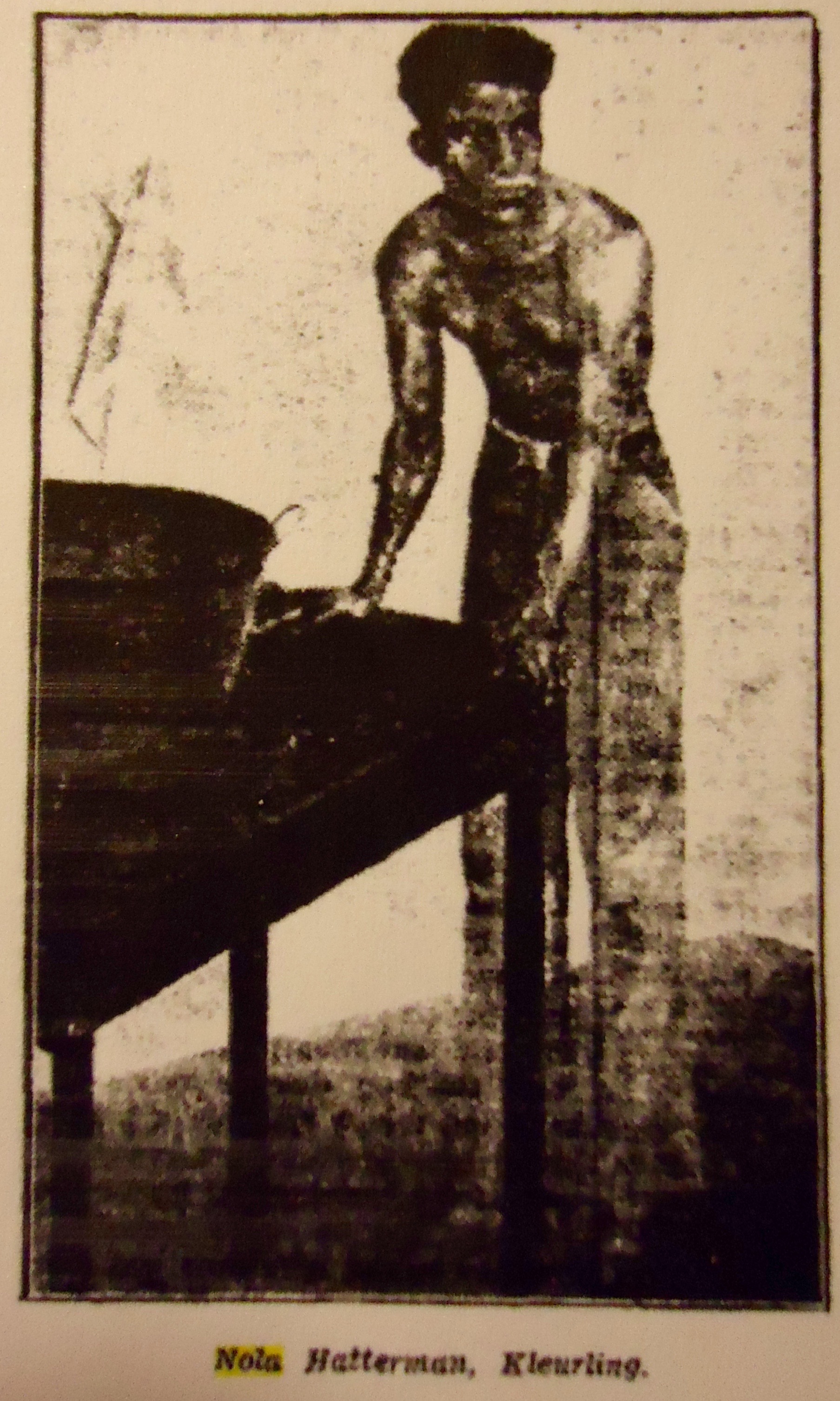

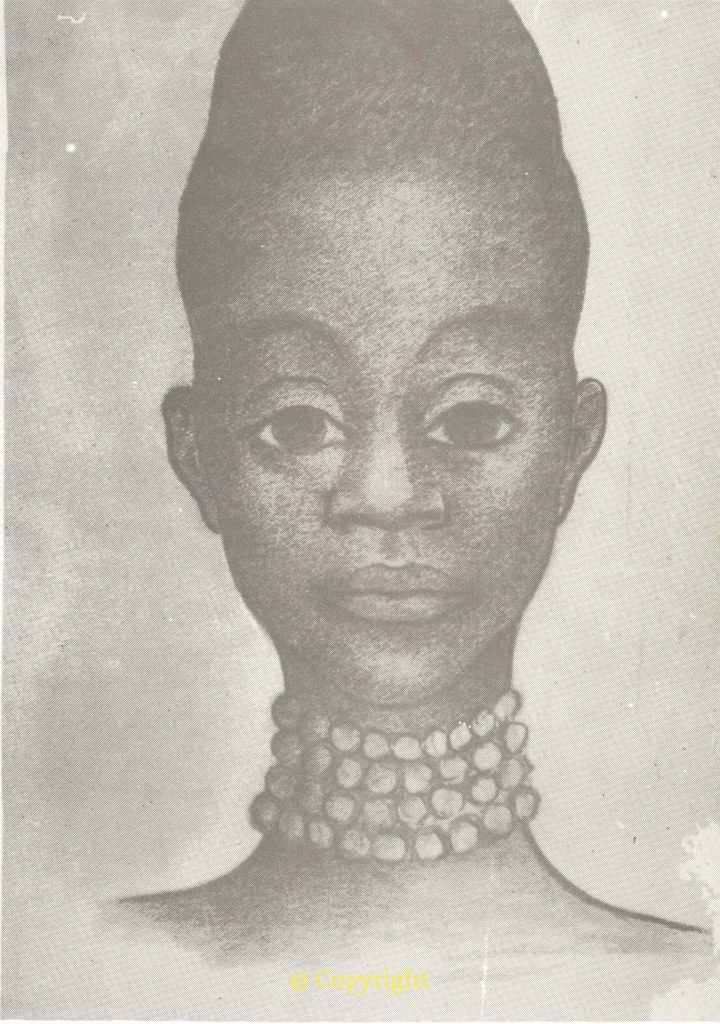

Above are images of works we are looking for. Unfortunately they ‘re not always of good quality. In De Nieuw Rotterdamsche Courant (24051929) I found a picture of her oil painting Kleurling (1929). Regarding the colour scheme: from the description it can be concluded that the ‘big figure, with the bare, yellow-brown torso’ wears blue pants. Elsewhere, in De Maasbode (05061929) the journalist speaks of ‘moody and somewhat sad blues and grays’. I’m very curious about this painting! Liggend naakt, Lying nude and Mevr. N., Mrs. N. were published in the monthly magazine for visual arts, June 1931 in an article of art critic Ro van Oven. Surinamese – also with the addition Frits Frezer – was in the catalogs of the artists’ associations Sint Lucas, De Brug and De Onafhankelijken (1930, 1931, 1932 respectively). The images were printed in black and white. Naakt, Nude, was auctioned at Sotheby’s in Amsterdam in 2001. In 1997 this auction house sold Ona. Possibly a work from 1926 (catalog De Onafhankelijken 1926). In 1999 the art historian Lia Ottes made a list of approximately 90 works by Nola Hatterman for her M.A. thesis Nola Hatterman, Haar leven en werk (her life and work), including the painting Jazz, jazz from (ca 1976). Paintings change hands in the course of time. Who is the current owner of this work? The avocado tree from 1956 was sold on Marktplaats three years ago. Again, the question is: who is its present owner?

The Gooi- en Eemlander of 5 June 1948 printed a review of a lost drawing of Nola’s, entitled Pasuka. Is this a portrait of the Jamaican/British dancer and choreographer Berto Pasuka? Is this the drawing described by Ottes as Head of an Indian? It is quite possible that Nola saw Pasuka’s dance company Les ballets nègres in London, where she stayed often. The company toured through Europe. Pasuka was inspired by Winti and Marron dances. The phenomenon of Les ballets nègres is a subject of post-colonial studies. Please also see the Facebook page.

Information about these works by Nola Hatterman is very welcome. Please report it via the Forum or Contact.

In this section a number of finds and works which have rarely or never been shown to the public.

EDUCATION

Pedagogue

Only after her departure in 1953 to Suriname, did Nola become a pedagogue. The only – so far known – student who taught Nola in Amsterdam was the Jewish ceramicist Brigitte Kray (1924-2018). Pos-Kray about Nola: ‘I learned the technique of working from light to dark and the skills needed for lithography. She was very serious in her profession.’ During her hiding period Brigitte was able to reach Nola’s studio in the Falckstraat without any problems. Under the assumption that the war would some time be over, she took lessons from Nola in preparation for the Art Academy. Kray, who married the director of the theatre school in Amsterdam: the Dutch-Surinamese Willy Pos in 1945, later recalled how the realistic artistic movement that Nola had represented ended after the war.

The Caribbean

Nola wanted to be sent to Suriname to teach at the Cultural Center Suriname (CCS). She asked the sister organization in the Netherlands, the Foundation for Cultural Cooperation (Sticusa), to send her out. But Nola was not welcome in Suriname because of her communist sympathies. In 1953 she boarded a ship on her own. First she visited Trinidad where she held an exhibition, next she visited Guadeloupe and then set sail for Suriname. She probably dropped her plan to visit Haiti and the art school of Dewitt. We do not know whether she planned to visit the school of Edna Manley. Once in Paramaribo, she gave lessons to its elite to provide for herself. Not long after, the CCS asked her to provide a course in painting, drawing, art history and anatomy. The successful course was developed in 1960 for the School of Fine Arts with Nola as director. The school focused on amateurs, but also provided a 2-year drawing course. Nola taught her students about the use of color in the tropics and developed a scheme for painting the ‘non-European type’. In Europe, Nola thought, there was little attention for the physiognomy of the black people. She reminded her students – the black psychiatrist and anti-colonialist Frantz Fanon in mind – that Suriname should no longer reflect on Europe. Suriname had to develop its own national art, with appreciation for its own culture and history. She believed that the European art schools ‘ruined’ her students.

Directional struggle

Nola was generous when it came to talented children from poor families who could not afford the tuition fees, such as Armand Baag and Soeki Irodikromo, but she was unrelenting in her crusade against abstract art. The critics made themselves heard. Especially her former pupil Jules Chin A Foeng rejected her artistic taste (her plea for realism), her focus on the Afro-Surinamese population and her teaching methods. According to Chin A Foeng – who experimented freely with Western art movements – Fanon’s call for decolonization did not relate to style but to education and ‘foreign’ frameworks. He started his own school and was followed. In 1967 Paramaribo counted but five art colleges, of which the Academy for Fine Art Foundation of Alphons Maynard trained for a Middle instead of a Lower Education Diploma. In 1968 Nola decided to upgrade her school independently to a comparable day course. Former student Ruben Karsters – just graduated from the Amsterdam Rijksacademie – would hold the scepter under the auspices of Nola. The Sticusa – lender of Nola’s education – was not amused.

Criticism

More criticism came. Art academies in the Netherlands where Nola’s pupils received further education, complained that Nola taught them wrong techniques. That Nola preferred realism to other art movements and detested abstract art, will have to do with it. Conversely, Nola stated that on Dutch art academies, students no longer learned any technical skills. CCS fired Nola in 1970. Sticusa was no longer willing to provide subsidies if the school did not change its course. This led to criticism by the poet Dobru who wrote in the Surinamese newspaper De Ware Tijd of 11 January 1971: “As if Stikusa (sic!) has to decide for us what is good for our country.” Such criticism on Sticusa and the CCS in the role of (colonial) lackey was not new.

At the age of 71 she started the New School for Visual Arts in her home. Nola decided that her education would be the first that would deliver independent artists, without intervention from the Netherlands. Her pupils were also no longer entitled to a scholarship to the Netherlands. Jules Brand-Flu, Wilgo Elshot, Soekinta and Rudi Chang were among the first batches to graduate in Suriname. Her last pupils, Rinaldo Klas and George Ramjiawansingh, received their certificate in 1976 from the Minister of Education, Ronald Venetiaan. At the end of the seventies Nola left for the interior of Suriname because the appreciation for which she craved did not come. She was somewhat disappointed. On behalf of the Culture department of the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport she provided drawing education for the children in Brokopondo together with her former student Stuart Manuel. Nola to her friend Anita Berggraaf just before she died in 1984: ‘Particularly invigorating and everything you want is working with my student Stuart Manuel. (…). We work well together, where it concerns preparing and giving the courses to the children here.’ In Brokopondo Center she would finally complete her historical works about slavery and resistance against it.

Nola Hatterman Art Academy (NHAA)

Despite all the contradictions, Nola was restored posthumously. After her death in 1984, it was decided to name the art academy after her in honor of her contribution to Surinamese art: the Nola Hatterman Institute. Nowadays: the Nola Hatterman Art Academy. Former student Rinaldo Klas has been a director for a long time, nowadays the management is in the hands of Kurt Nahar and Sunil Puljhun. In 1997, the Vereniging Ons Suriname, initiated by Delano Veira and Nola’s student Armand Baag in Amsterdam, opened the Galerie Nola Hatterman. Armand Baag had according to his descendants, in a way, followed in her footsteps by choosing the Afro-Surinamese as the subject of his work. He applied the techniques he learned from Nola in his own style, palette and use of colour. Myra Winter – enthusiastic advocate of Nola and Surinamese art – swung the scepter for a long time, and was later succeeded by Joan Buitendorp. The gallery acted as an air bridge between the two countries. Another bridge between 2006 and 2014 formed the exchange program between the NHAA and the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. The teaching methods have now partly changed, but in the spirit of Nola, the current NHAA tries, under the motto ‘Talent first’, to introduce children from 6 years to art through the Youth Academy. A number of them continue to the four-year art education that offers talented young people the opportunity to develop into autonomous, visual artists.

Lately, in the postcolonial debate raging in the west, the position of Nola as a white painter of black models and teacher in a colonial setting is (once again) under discussion. In Suriname this is not the case. Nowadays she is seen as one of the Surinamese painters.

Pupils

A procession of pupils who later wether of not made art their profession, took lessons from Nola, in the Netherlands: Brigitte Pos-Kray, in Suriname: Armand Baag, Jules Chin A Fung, Ruben Karsters, Frank Consen, Soeki Irodikromo, Jules Brand-Flu, Doelmajid Soekinta, Rudi Chang, Wilgo Elshot , George Ramjiawansingh, Rinaldo Klas, Jozef Klas, Johan Pinas, Ilse Vreugd, Lies Franklin, Humphrey Windsock, Welsh De Vlugt, Arnold Ritfeld, Ara, Stanley Brouwn, Robbert Doelwijt, Milton Kam, George Grimmère, Roy Dorder, Roy Yang, Henna Rommy, Henna Lakisaran, Laurence Lieuw A Po, Merle Leiles, Lyn Panatjok, Khedoe, Carlos Blaaker, Chris Healy, Kenneth Flijders, Shamanee Kempadoo, Stuart Manuel, R. Crislau, Ricardo Melcherts , and many, many others. If you are acquinted with any other students, please send an email or report it to the Forum.

OEUVRE

If you want to get acquainted with a selected oeuvre overview (in PDF format) of the artist Nola Hatterman (1899-1984), this is possible. But there are some conditions attached to it. Download the form. Please fill in, sign it and email to: ellen@ellendevries.nl or print it out and send it to:

dr. Ellen de Vries, Onderzoek & Multimedia producties

Majubastraat 6 D

1092 KG Amsterdam

The Netherlands

After signing and receiving this document, Ellen de Vries will contact you.

ABOUT

The project The legacy of Nola Hatterman is an initiative of Dr Ellen de Vries. She is interested in (images of) the (post) colonial relationship between the Netherlands and Suriname. In 2015 she got her PhD in media research on the role of Dutch and Surinamese media in the postcolonial relationship between the Netherlands and Suriname in the turbulent 1980s. In 2017 the commercial edition of this thesis, Mediastrijd om Suriname, appeared at the WalburgPers (in Dutch). She previously wrote the biography Nola, Portrait of a self-willed artist (2008, 2009, e-book 2017). This book has not been translated yet, except for the Prologue and Chapter 1. In this project Ellen de Vries acts as a researcher and project broker with the support of the Mondriaan Fund.

Partners in this project:

. Producer and filmmaker In-Soo Radstake

. Cultural entrepeneur Myra Winter

. Dr Elmer Kolfin (University of Amsterdam/ RKD), trainee Sophia Lasschuijt

. Dr David Duindam & Dr Aylin Kuryel (University of Amsterdam), trainee Eline de Jong

. Prof. Dr R. Hoefte (University of Amsterdam/ KITLV), trainee Marlou Heijnen

Supporting statements: various organizations and individuals have expressed their appreciation for this project: the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, art historian at the University of Amsterdam (UvA) Dr Elmer Kolfin, also employee RKD , Museum Arnhem, the Nola Hatterman Art Acadamy, Prof. Michiel van Kempen (University of Amsterdam), Prof. Dr. Kitty Zijlmans (Leiden University), Uitgeverij Waanders & De Kunst, art and culture manager Ada Korbee, art historian Paul Faber, former gallery owner of the Galerie Nola Hatterman (Amsterdam) Myra Winter.

Colophon: Ellen de Vries is responsible for the texts. Reinier Mathijsen made the website, the logo is from Janneke de Jonge. With thanks to Willem Rueb who supplied the photograph of Nola’s self-portrait in the logo. Carolien Schamhardt is responsible for the translation.

Copyrights:

The copyright of the website text rests with Ellen de Vries. Copying of information is permitted provided that the source is mentioned.

The copyright on the work of Nola Hatterman rests with the Erven Hatterman.

FORUM AND CONTACT

Would you like to leave a comment or make contact? Go to the Forum or Contact.